Joshua Marshall

Establishes a clear problem and/or opportunity and justifies the design

decision and development of materials and or processes as an appropriate

strategy to solve the problem or take advantage of the opportunity.

Justifies and defends design decisions based on established models

and/or project-based contextual factors that dictate the need to not

follow a prescribed model.

During my studies, I have had the opportunity to use a number of

design and development models. Some models are systems based, such

the MRK or Dick and Carey model, while others are best used only in

certain situations, such as the NTeQ model for technology integration or

the Planes model for end-user experience design.

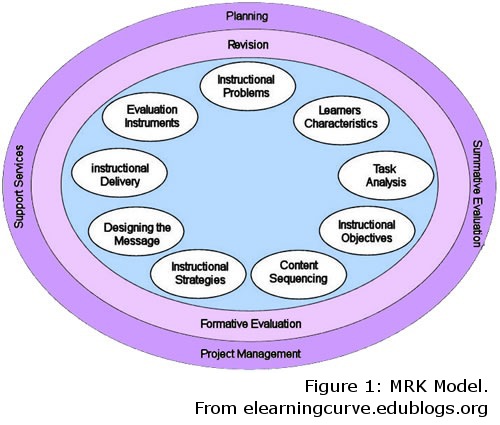

One instructional design model that I have become familiar with

is the Morrison, Ross, and Kemper (MRK) model. Looking at the picture

below, we can see that the MRK model is very different from traditional

systems models.

Instead of a flow chart, we are presented with a set of circles

and bubbles. This graphic

representation of the model illustrates it flexibility.

Notice that there are no lines connecting each phase, meaning the

designer is free to complete the phases in the order that makes the most

sense for each individual project.

This reflects the true nature of the design process.

For example, I have had to go back and re-write learning

objectives when developing assessment strategies to bring them more in

alignment. With a

traditional linear model, this would be discouraged.

I find this heuristic approach to be very exciting, although it

can at times be disconcerting attempting to view a large project in this

fashion. When working on a large design project, I will often

divide it into sections, which can sometimes be counter-productive with

the MKR model. However, understanding the inter-relationship of

each phase of the process, which the MKR model excels at, enables one to

create a more coherent design than otherwise possible.

I created this instructional design documentation

packet in Dr. Knowlton's IT 510 class working with the MRK model.

The actual instruction may be found

here. The content I chose to use for working with this model

was candle making. This model worked well in this case because it

required me to develop generative strategies, which would help the

learner formulate and carry out their own design decisions in making

their candles. The instruction contained both behaviorist goals

requiring the learner to demonstrate specific skills like molding the

wax, as well as cognitive goal requiring the learner to remunerate on

the candle making process and justify their design decisions. The

MRK model is perfect for providing a coherent framework for a variety of

learning objectives and the instruction was successful in teaching a

novice how to create candles.

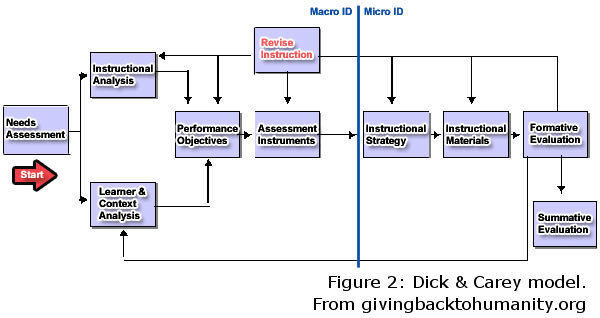

One model that takes a different approach than the MRK model and

is also very popular in the industry is the Dick and Carey model (1990).

This model is very linear in its layout, although it does have some

feedback loops built into it, directing the designer to revise their

instruction at each point in the model. Looking closely at Figure

2 below, one can clearly see that it is derived from

another I will discuss later, ADDIE (Analyze,

Design, Develop,

Implement,

Evaluate).

It has all of the same features as ADDIE, but then adds more or

divides them into separate steps. While ADDIE would have the

designer simply Analyze, the Dick and Carey model requires the designer

to conduct an instructional analysis and identify entry behaviors and

learner characteristics. From there the designer would develop

objectives and assessments, and then finally move on to crafting the

individual lessons. This

latter portion, as denoted in the graph, is labeled Micro Instructional

Design. The model is also

behaviorist in thought, as opposed to the MRK model which works quite

nicely with either behaviorism or cognitivism.

Although I have not had the opportunity to use the Dick and Carey

model in this program, thanks to the direction of Dr. Knowlton I have

spent considerable time learning its nuances because it is

a very prominent model in the industry.

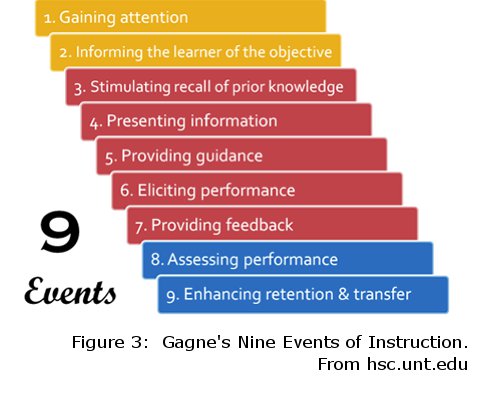

Another model I have grown fond of is Gagne's Nine Events of

Instruction (1992). Although there are several steps to remember,

I find it to be a very straightforward yet elegant model. This

model, see below, can be divided into three distinct phases.

The first phase, called the pre-instructional phase, is meant to

"whet the appetite" of the learner.

This can be done through using instructional strategies such as

setting up cognitive dissonance within the learner, or posing what may

seem to be an intractable dilemma .

The second stage, the instructional phase, is where the bulk of

the designers effort will be spent.

Finally, we have the post-instructional phase where the designer

will devise mechanisms evaluate learner performance and instruction

effectiveness.

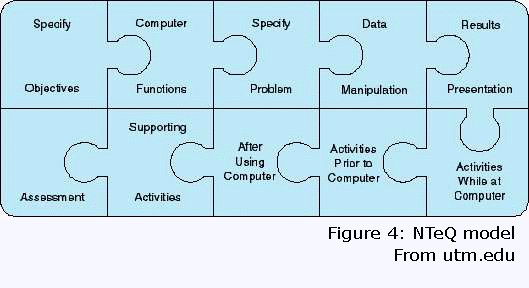

The NTeQ model developed by Morrison and Lowther (2011) also

takes a more linear approach to the design process. What I

particularly like about this model is that although it assumes the

inclusion of computers to aid in learning, it goes to great lengths to

ensure that not only do the computers serve a legitimate learning

purpose, but that each lesson is student centered.

Notice that in this graphic each stage of the process is

represented as a puzzle piece.

This illustrates the idea that if the designer takes the time to

properly use the model and develop appropriate activities, the sum

effect of the resulting unit will be greater than its constituent parts.

The NTeQ model is designed to be used for K-12 school teachers,

however keeping these general principles in mind can be beneficial in

any instructional design context. I created

this

sample unit in Dr. Thomeczek's IT 481 class. The purpose of the unit was

to help student's utilize computer resources to learn more about local

history. The NTeQ model is perfectly suited to this type of

instruction because it forces the designer to make clear decisions about

what the learners will be using the computers for exactly, as well as

supporting activities before and after the lesson. Because this

model is best suited for a situation when technology integration is

required, I consider it to be a micro-model along with Gagne's.

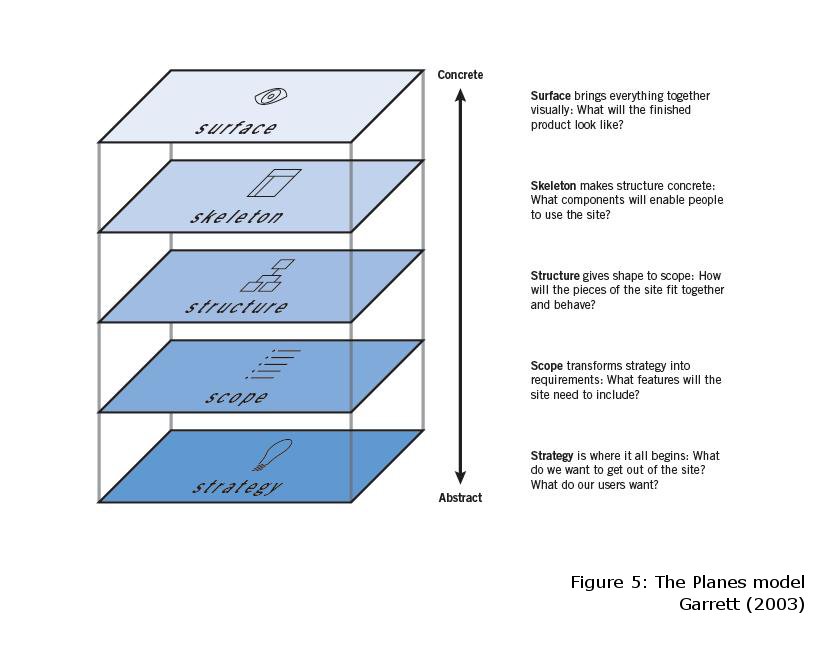

Another micro-model that is also technology based is the Planes

model from Garrett (2003). This model was developed to give a

graphical representation to what user-experience design (UXD) should

strive for. The model consists of a series of planes, beginning with the

user needs and the sites objectives, or the Strategy plane as Garrett

calls it, and progressing through to the Surface plane, which is what

the user will see. Each plane in the model represents a series of

decisions that the designer has to make, such as what will the

information architecture look like, how will the interface function and

so on.

I used the principles of this model when developing a

website for a local charter

school that will soon be opening. In the case of the website, I worked

with the client to get a good idea on the overall look and feel of the

site, and then I had to develop it based on what I thought would be of

most use to the user. In this case, I made the site very simple to

use with a very straightforward architecture. I did this because I

felt that the audience for this site would be the parents of inner city

school children and their familiarity with computers and technology

could not be assumed.

The last micro-model I would like to talk about is the ARCS (Attention, Relevance,

Competence, Satisfaction)

model developed by Keller (1987). This model is meant to

help the designer address the motivational needs of the learner.

Each phase of the model requires the designer to ask certain questions.

For example, for Attention the designer will have to address how to

capture the learners attention and how to create an inquiry arousal.

For Satisfaction the designer must devise opportunities for the learners

to use the new skill or knowledge, and to foster a positive feeling

about the learning accomplishment. Answering these questions, and others

derived from the model, will help the designer "get the students to give

the time and intensity of effort necessary in order to learn the

required knowledge and skills" (Gagne, 1992, p. 117).

ADDIE (Analyze,

Design, Develop,

Implement,

Evaluate) , although sometimes criticized for being too general to

be of any real use, does have a place in the repertoire of the designer.

What others may find it vague and general, I consider it flexible,

meaning that at the least it provides a solid starting point, regardless

of the project or content. This has real value for the designer

because one can start addressing each component of the design process

before finally settling on another model that will may be better suited

to the task at hand. This project management

plan was developed for Dr. Nelson's IT 530 class using the ADDIE

model. Although it may be vague and slightly nebulous, ADDIE

was the perfect model in this instance because the project was operating

at a macro level. The problem in this case that ADDIE so perfectly

met was that there was a variety of design processes occurring

simultaneously, such as graphic and sound production, and web design.

This meant that ADDIE could function as a project management tool and

life-cycle model, while other design models would function beneath it to

carry out the individual content development.

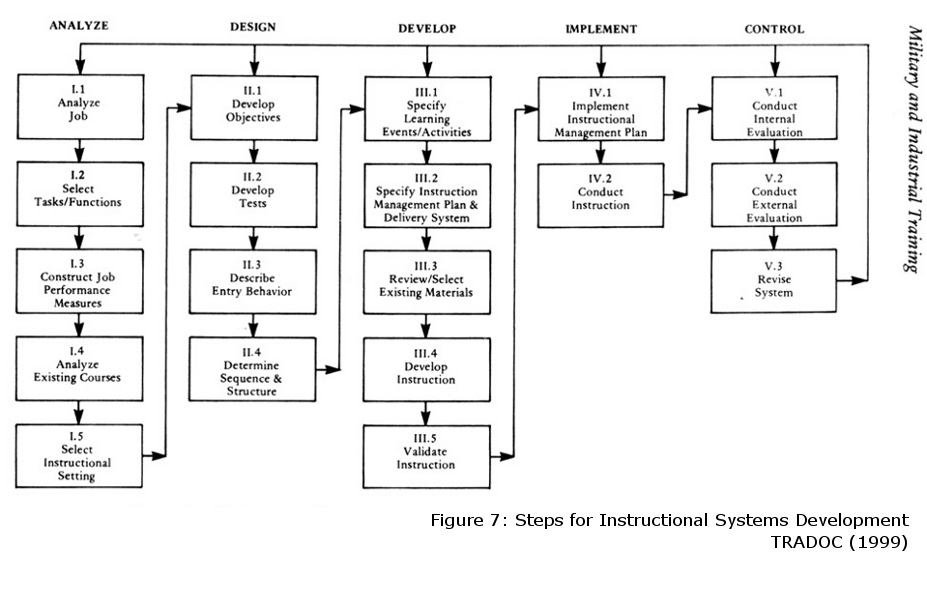

Because I am interested in eventually working for the Army as

civilian in their Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), I did some

research to learn more about what model they use.

TRADOC uses ADDIE, not as a model, but as a philosophy.

In their Systems Approach to Training white paper, they note that

most, if not all, instructional design models are simply elaborations on

ADDIE. The Figure 6 below

illustrates how the Army views the instructional design process.

The

instructional designers of the Army recognize that this is very vague

and aknowledge that the graphic is a simplification of the process.

In the following picture from their instructional development

technical manual, we can see that they outline the procedures that ADDIE

only implies.

I recently had a job interview for an instructional design internship at

the Technical Training Center at Anheuser Busch. During the

interview, the manager asked me what models I am familiar with and I

began to recount some of the models I have worked with so far. I

ended my response with "...and then of course there's ADDIE." The

manager smiled and said "Yep, that's what we use here." Based on

my conversations with others in the field, the use of ADDIE is common

and having a solid understanding of it will serve me well.

During the spring 2011 symposium, Dr. Nelson asked a very

interesting question: "what exactly is a model?" This simple

question is very thought provoking. My answer would be that a

model serves as a tangible representation of a thought process.

While the instructional designer may develop their own personal model

and internalize it, the more popular and well known models act as

commonality, a lingua franca

of instructional design. Most of the models I have seen share

common traits, such as know the learners, develop objectives, design

well thought out instructional strategies, and devise a method of

assessment. In other words, most instructional design models seem

to be outgrowths and refinements of ADDIE and any model will work if

applied appropriately. By appropriately, I mean that the designer

must choose a model that best fits the design project at hand, rather

than trying to fit every project into a pre-determined model.

References

Altalib, S. (2011),

Instructional design and

development theme. Retrieved from

http://www.givingbacktohumanity.org/saifaltalib/experiences/index.html

ComTek (2000), Systems

approach to training process study. Florida State University.

Dick, W. & Cary, L. (1990),

The systematic design of instruction

(3rd Ed.) Harper Collins

Gagne, R., Briggs, L. & Wager, W. (1992).

Principles of instructional design (4th

Ed.).

Fort Worth, TX: HBJ College Publishers.

Garrett, J. (2003). The elements

of user experience: user-centered design for the web.

New York, NY: American Institute of Graphic

Arts.

Hanley, M. (2009). Discovering instructional design 11: The Kemp model. Retrieved from

www.elearningcurve.edublogs.org/2009/06/10/discovering-instructional-design-11-the-kemp-

model/

Keller, J.M. (1987). The systematic process

of motivational design.

Performance and

instruction, 26(9), 1-8.

Morrison, G., Kalman, H., Kemp, J., & Ross,

S., (2011). Designing effective instruction.

(6th Ed.).

Hoboken, NJ: Wiley and Sons.

Morrison, G. L., Lowther, D. L.,

(2011). Integrating computer technology into the

classroom

(4th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill, Prentice Hal

Spaulding, M. (2011). NTeQ.

Retrieved from

http://www.utm.edu/staff/mspaulding/311/311nteqform.html

(TRADOC),U. S. A. T. A. D. C. (1999). Systems approach to training management,

processes, and products. Fort

Monroe: Department of the Army.

UNT Health Science Center, Center for Learning and Development. (2011). Course design -

teaching strategies. Retrieved from

www.hsc.unt.edu/departments/cld/CourseDesignTeachingStrategies.cfm