Learning Theory

Teaching Online uses the Adult Learning Theory extensively. Adult learners are self-directed are goal-oriented. They like to be involved in the learning process and don’t like to waste time (Collins, 2004, Kenner & Weinerman, 2011). From experience I know that faculty are busy and do not have time for long extended classes nor waste time with unnecessary work. Therefore, in following the adult learning theory, this course has been designed in short modules that can be completed at the participant’s own pace. While the assessments will be reviewed, the completion of one module is not dependent upon finishing a previous module.

Adult learners prefer authentic assessments, or work that is meaningful and useful. Authentic assessments include learning through “real-world tasks” (Swaffield, 2011). The assessments in this course will ask the participant to reflect on a reading or video and apply it to the course or discipline they teach. Connecting the assessment to something personal will make the assessment more meaningful to each participant as well as give them a basis for their own teaching.

Content Sequencing

Morrison, Ross, Kalman & Kemp (2011) define sequencing as the “effective ordering of content in such a way as to help the learner achieve the objectives.” I have divided the learning outcomes into four modules, Getting Starting Teaching Online, Understanding the Online Student, Online Communications, and Online Assessments. The Course Orientation module containing the welcome video and pre-course survey and the post-course survey are separate.

Table 1 displays the sequence of the objectives and learning outcomes by module.

Table 1 |

||

Module |

Objective |

Learning Outcome |

GETTING STARTED |

Understand the differences between teaching face to face and teaching online |

|

Understand various time management skills for online teaching |

|

|

Know the essential parts needed in an quality online syllabus |

|

|

ONLINE STUDENTS |

Understand the qualities and motivations of the online student |

|

COMMUNICATION

Student-student |

Understand best practice of faculty-to-student communications |

|

Understand the best practices for engaging students in communication with each other |

|

|

ASSESSMENT:

Evaluating |

Demonstrate how to correctly align course objectives to online assessments |

|

Demonstrate the best practices for designing assignments and assessments using rubrics |

|

|

Demonstrate the best practices for evaluating online course |

|

|

Instructional Strategies

Morrison, Ross, Kalman & Kemp (2011) identify six types of content that each instructional objective falls into: fact, concept, principles and rules, procedures, interpersonal and attitude. Each content type has a corresponding performance of either recall or application. Recall falls lower on Bloom’s Taxonomy whereas application involves understanding and executing which are higher on Bloom’s Taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002). Table 2 displays the learning objectives and instructional strategy by module.

Table 2 |

||

Module |

Objective |

Instructional Strategy |

GETTING STARTED |

Understand the differences between teaching face to face and teaching online |

Concept - application |

Understand various time management skills for online teaching |

Concept - application |

|

Know the essential parts needed in an quality online syllabus |

Concept – application |

|

ONLINE STUDENTS |

Understand the qualities and motivations of the online student |

Concept – application |

COMMUNICATION

|

Share best practices of online synchronous and asynchronous communication with students |

Concept – application |

Know the best practices for engaging students in communication with each other |

Concept – application |

|

ASSESSMENT:

Designing

|

Demonstrate how to correctly align course objectives to online assessments |

Concept – application |

Demonstrate the best practices for designing assignments and assessments |

Concept – application |

|

Demonstrate the best practices for evaluating online assessments |

Concept – application |

|

Learning Activites

Designing the Message

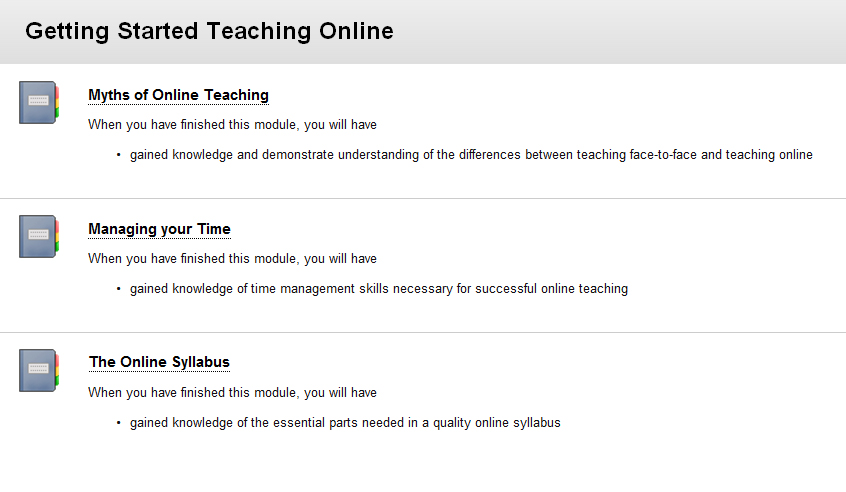

Meaningful learning depends on the proper selection of words and multimedia, the organization of the materials, and the integration of the learning with prior knowledge (Mayer, 2010). Each module (Getting Started, The Online Student, Communications and Assessments) are divided up into learning units designated by the learning objectives. Within each module one to three learning units, based upon the learning objectives. Each Learning Unit consists of (an) article(s) to read and/or video to watch for the instructional portion. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – “Getting Started Teaching Online” Module

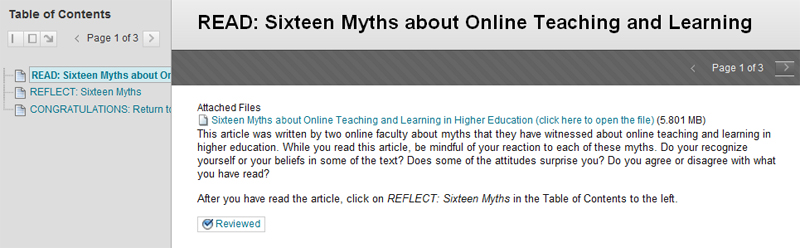

People learn better when they explain, put into their own words or summarize the materials (Mayer, 2011). Each assessment for the learning unit consists of either a reflection or a submission. In the reflection, the participant will apply the new knowledge to something within themselves (reflecting on their feeling toward a myth). In the apply submission, the participant will connect the new knowledge to their online course (apply the lesson to their course syllabus). The learning unit allows the participant to work, step by step through the unit. See Figure 2.

Figure 2 – “Sixteen Myths about Online Teaching and Learning”

Table 3 describes the Course Outline as it is aligned with the course objectives.

Table 3 |

||

Module |

Objective |

Lesson plan/course outline |

GETTING STARTED |

Understand the differences between teaching face to face and teaching online |

|

Understand various time management skills for online teaching |

|

|

Know the essential parts needed in an quality online syllabus |

|

|

ONLINE STUDENTS |

Understand the qualities and motivations of the online student |

|

COMMUNICATION

Student-student |

Understand best practices of faculty-to -student communications |

|

Understand the best practices for engaging students in communication with each other |

|

|

ASSESSMENT:

Designing

Evaluating |

Demonstrate how to correctly align course objectives to online assessments |

|

Demonstrate the best practices for designing an assessments using rubrics |

|

|

Demonstrate the best practices for evaluating online courses |

|

|

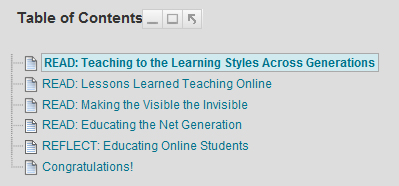

Development of the Instructions

Morrison, Ross, Kalman, and Kemp (2011) supports the belief that self-paced learners retain more when they set their own pace. A successful self-paced instruction must be broken into small units containing a single concept with a confirmation of mastery at the end of each step. Each learning unit is comprised of (an) article(s) to read and video to watch. The learner can read or watch each segment and have the ability to return to one as necessary. See Figure 3 for the Table of Contents for The Online Student module. This module has 4 short articles to read about a different type of student. The self-paced learner may not wish to or have the time to read all the articles at once. The Learning Unit tool allows the learner the ability to see what content is available. The Learning Unit tool also allows a learner to click a “Mark Review” button to mark off when an item is complete. If a learner does not complete the learning unit in one sitting, the Mark Review will remind the learner what has been completed.

Figure 3 – Table of Contents for” The Online Student” module

Morrison, Ross, Kalman, and Kemp (2011) also identify the lack of instructor-learner interaction as a limitation of self-paced learning. For instructors to overcome this limitation, thorough instructions and directions are necessary within each item in each unit. Moore and Kearsley (2012) states that it is the role of the instructor is to facilitate the interaction between learner and content. This facilitation occurs not only in communications between instructor and learner but within the instructions in the learning units and assignments.

In the “Getting Started Teaching Online” module, in the first learning unit, the participants are asked to read the article “Sixteen Myths about Online Teaching” and then reflect on it. Because this the first learning unit, more details are needed in the instructions in order for the participant to receive a deeper understanding of the article and to be able to connect with the article as an adult learner.

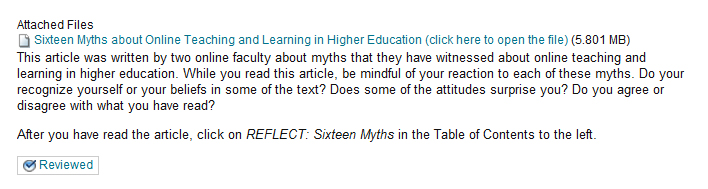

Figure 4 – Instructions for Readings

In Figure 4, there are 3 separate sets of instructions for the participant to follow. First, the participant may not know how to access the file. The change of text color should identify a link to most web users, but one can never assume anything about the learner. Therefore, next to the title of the article is the instruction “Click here to open the file.” Future learning units do not need this set of instructions because the participants should realize that the blue text indicates a link or file.

The second set of instructions is the first paragraph under the link. Not only do the instructions offer a brief introduction to the article, but indicates what the participant should be looking for in the article. This gives the participant a framework of what is to be expected in the reflection.

The third set of instructions is the last line indicating to the participant what he/she should do when they have finished the article. One should not assume that the participant knows to click on the second item in the Table of Contents of the learning unit. Like the first “click here” instructions, this one may be repeated in the next learning unit, but not necessarily throughout the remaining modules as the learners get used to the structure of the course.

Once the participants follow the instructions to the Reflection, the assignment instruction (in yellow) explain what is expected in the assignment. The directions to use the tool are highlighted in green. See Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Instructions for Reflection Assignment

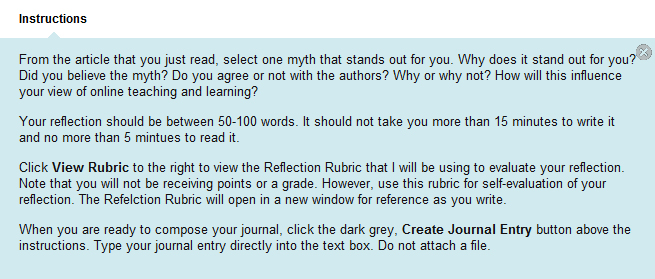

After the participants have opened the Journal, more detailed instructions are include length of refection and directions for the assessment rubric. See Figure 6.

Figure 6 – Instructions for Journal

Hardware

- PC, Mac or mobile devise

- An internet connection, preferably high-speed

- Headphones or speakers for audio playback

Software

- Blackboard is the course management system utilized for this project.

- Standard Browser – Internet Explorer 8 or higher; Firefox 18 or higher; Safari

- Blackboard Mobile Apps for iPhone, iPad and Android

- The videos on Blackboard are powered by YouTube and can be viewed on PCs, Macs and most mobile devices without any additional software.

- Participants will be expected to have Adobe Reader installed in order to view the articles. A word processing program such as Microsoft Word is optional.

Formative Evaluation

A formative evaluation will be conducted by several of the Instructional Designers from the ITS’s IDLT center prior to the release of the course. Changes will be made according to their recommendations.

Resources

Collins, J. (2004). Education Techniques for Lifelong Learning, RadioGraphics, 24(5), 1483-1989.

Kenner, C. & Weinerman, J. (2011). Adult Learning Theories: Applications to Non-Traditional College Students. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 41(2) 87-96.

Krathwohl, D. (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218.

Mayer, R. (2010). Seeking a science of instruction. Instructional Science, 38(2), 143-145.

Mayer, R. (2011). Applying the Science of Learning to Multimedia Instruction. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, (55), 77-108.

Moore, M. and Kearsley, G. (2011), Distance Education: A Systems View of Online Learning (3rd edition). Wadsworth Publishing.

Morrison, G., Ross, S., Kalman, H., and Kemp, J. (2011). Designing Effective Instruction. Hoboken, NY: Wiley & Sons.

Swaffield, S. 2011. Getting to the Heart of Authentic Assessment for Learning, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(4), 433-449. Retrieved from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838