ENG208 -- Survey of British Literature: Beginnings to 1789

Prof. Eileen Joy (Fall 2004)

CRITICAL ESSAY

Due: Tuesday, Dec. 8th

For your essay--a CLOSE READING/LITERARY ANALYSIS exercise--develop a narrowly-defined argumentative thesis related to a comparison of some aspect, or aspects, of TWO works we have read thus far (ranging from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight through Paradise Lost), and write a paper of approximately 4 typed (double-spaced) pages (MLA-style citation and documentation). NO outside sources are to be used for this paper, which should solely represent your own critical and analytical thinking. I would really prefer that you develop your own thesis without my assistance, but the following list represents some rudimentary "themes" and broad ideas within which you might begin to develop a more specific thesis:

SOME GUIDELINES FOR WRITING

(I would like to note here that the following comprises some of own thinking, tips culled from The Holt Handbook [6th ed.; pp. 723-26], and from Professors DeLombard's and White's "Papers: Expectations, Guidelines, Advice and Grading," available online here.)

First, Please keep in mind that when I ask you to do a close reading of a literary text (or two) in order to interpret its possible messages, that you do not read to magically discover the ONE correct meaning the author has supposedly hidden between the lines. The "meaning" of a literary work is created by the interaction between a text and its readers, and therefore, most works of literature can convey many different meanings to different readers. Do not assume, however that a work can mean whatever you want it to mean; ultimately, your interpretation must be consistent with the stylistic signals, thematic suggestions, and patterns of imagery in the text. Therefore, in a close reading, whatever observation you want to to make about what you think the author/text is doing/saying, be sure to ALWAYS support your interpretation with direct reference to the text itself (both by providing brief summaries of key content and also by the use of direct quotation).

Here are some TIPS on how to go about doing a close, interpretive reading:

In order to become a good interpreter of literature, you will have to make the important distinction between summary and translation, on the one hand, and interpretation or analysis, on the other. When you summarize, you repeat what the text actually says; when you translate, you explain to your audience in some detail many of the points an astute reader would reach on his or her own -- think of translating something from French into English for a person who speaks both languages. Neither summary nor translation is really a worthwhile endeavor in that neither tells the reader anything he or she did not already know. By contrast, when you interpret or analyze literature, you produce your own ideas about how the text creates meaning. In order to produce these ideas, you will need to perform close reading, to look closely at the language of the text in order to demonstrate not just what you think the text means, but more importantly how it means what you think it does. See the difference? It's an important one.

How, then, do you go about interpreting and analyzing rather than merely summarizing or translating a text?

In carrying out your close readings, then, your goal is always to do two things:

As you reread your paper during revision, when you come to each quotation, ask yourself: "Do I interpret the language of my quotations in detailed and specific terms?" "Is it clear how my close readings support the topic sentence of the paragraph, and thus the thesis of the paper?"

Summary and translation reproduce what the text says. Persuasive interpretation says what the text means by showing, through close reading, how the text means what you say it means.

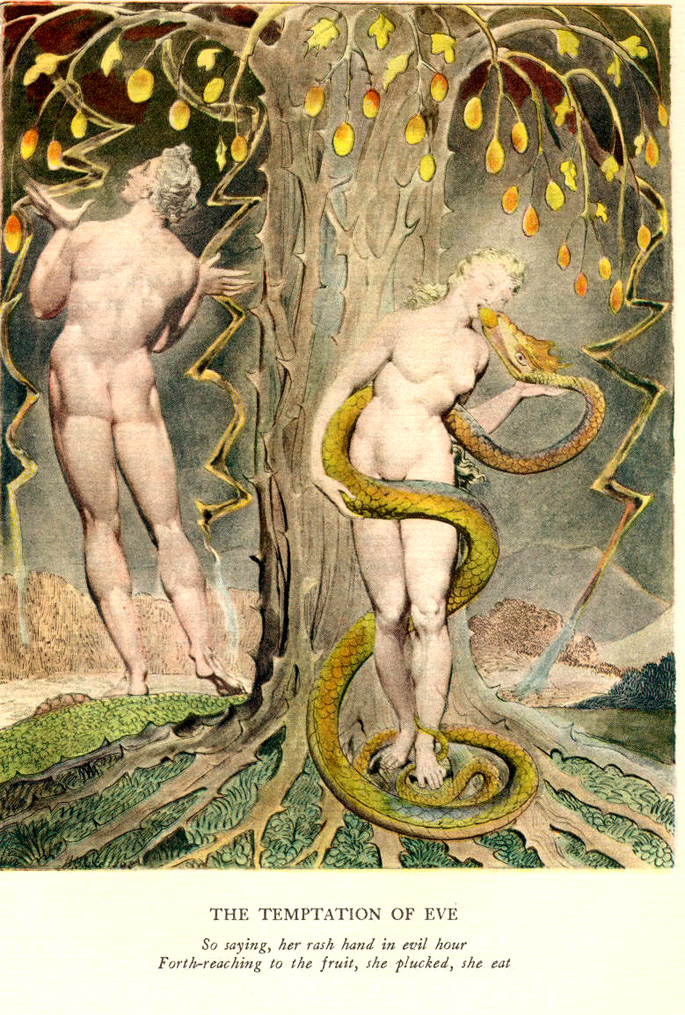

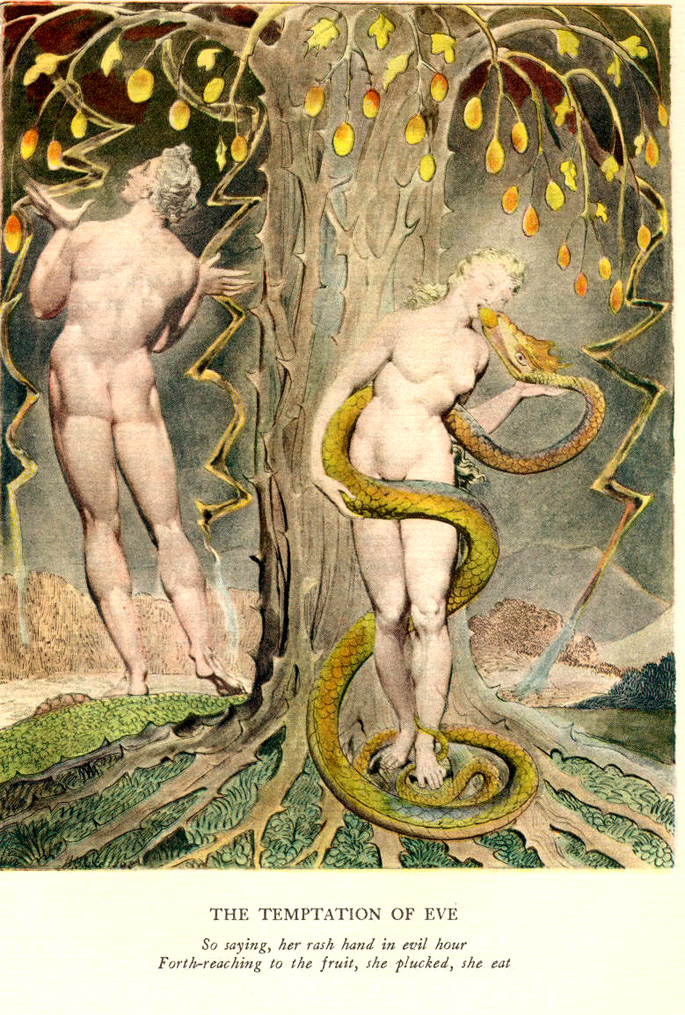

Second, I expect to see a thesis near the beginning of your paper. In other words, I want you to have some kind of point you would like to make/argue in relation to the topic you have chosen. For example, if you decide to compare and contrast Duessa and Tamora as "evil women," I don't want a paper in which you simply catalogue the similarities and differences in their respective actions and beliefs, and then conclude by saying something like, "So, as is evident, Duessa and Tamora are both bad, bad women, who are really evil." I want you to have a more pointed idea that results from your comparison of the two women. For example, you might want to argue that, even though both Duessa and Tamora are evil women who try to destroy the hero (Red Crosse Knight and Titus, respectively), Tamora is ultimately more empathetic because her motivation for wanting to destroy Titus is understandable (Titus defeated her country, carried her and her children to Rome as war slaves, and sacrificed her oldest son), whereas we never really understand why Duessa does the things she does. OR, if you want to compare the "monsters" in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Book I of The Faerie Queene, I don't want a paper in which the thesis is, "There are interesting monsters in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Book I of The Faerie Queene," but rather, something like, "Both Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Book I of The Faerie Queene have male and female villains, and also monsters, who try to destroy the hero, but it is the monsters who ultimately show the hero who he really is deep down." OR, if you want to compare Aaron the Moor from Titus Andronicus and Satan from Paradise Lost, I don't want you to argue, "Aaron the Moor and Satan are both bad dudes who never repent their sins." A more interesting argument might be something like, "Both Aaron the Moor and Milton's Satan appear to be completely unrepentant evildoing monsters, but there are certain moments when they show a different, more human side that complicates how we ultimately judge them." And so on and so forth.

NOTE: You are NOT allowed to reuse an essay topic from the mid-term exam, unless it is your intention to take that topic in a new and better direction. Consult with me on this if that is what you want to do.

Here are some TIPS on how to develop a good thesis:

Your introductory paragraph should do two things: introduce your reader to your topic and present your thesis. It is important to distinguish in your mind between your topic -- what you will write about -- and your thesis -- what you will argue or attempt to prove. A thesis may be defined as an interpretation that you set forth in specific terms and propose to defend or demonstrate by reasoned argumentation and literary analysis. Your thesis, then, is the position that you are attempting to persuade your reader to accept.

Your thesis may be more than one sentence long. If you have a good thesis, however, in most cases you will be able to articulate it in one sentence. If you require two, that's fine, so long as you make sure that the argument is coherent and that the transition from the first to the second sentence is clear and effective.

Please carefully consider this important hint: You do not need a refined thesis in order to start writing. If you begin with a provisional thesis and then do good and careful close readings, you will often find a version of your final thesis in the last paragraph of a first draft. Integrate that version into your first paragraph and revise from there. Do not worry too much about your thesis, therefore, until after you've written out your close readings! A good final thesis should emerge from, not precede, your analyses.

Below are five steps that will help you work through the process of developing a strong thesis. First, though, please think about these three guidelines:

Now that you've attentively read and considered these guidelines, here are five concrete steps that you can take to develop a thesis and start writing the paper. Note that we do not say "five easy steps." All of these steps require work, especially the fourth.

Other Considerations: