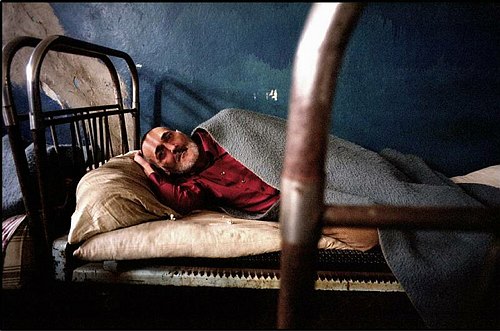

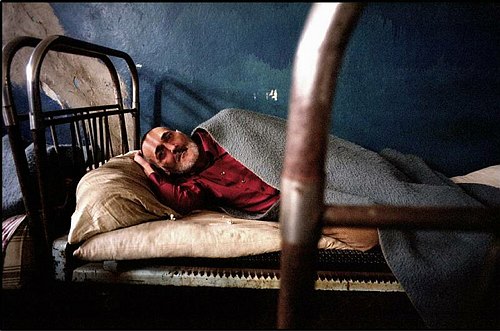

Chechen Man at Samaski Mental Hospital, Grozny -- February 2002 (Eddy van Wessel, copyright)

"The Elsewhere Ghosts of Beowulf" [paper presented at the 38th International Congress on Medieval Studies, 8-11 May 2003, Kalamazoo, Michigan]

"Time is not the achievement of an isolated and lone subject, but . . . is the the very relationship of the subject with the Other. This thesis is in no way sociological. It is not a matter of saying how time is chopped up and parceled out thanks to the notions we derive from society, how society allows us to make a representation of time. It is not a matter of our idea of time but of time itself. To uphold this thesis it will be necessary, on the one hand, to deepen the notion of solitude and, on the other, to consider the opportunities that time offers to solitude." (Emmanuel Levinas, Time and the Other, trans. Richard A. Cohen [Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1987], 39)

"He who does not realize to what extent shifting fortune and necessity hold in subjection every human spirit, cannot regard as fellow-creatures nor love as he loves himself those whom chance has separated from him by an abyss. The variety of constraints pressing upon man give rise to the illusion of several distinct species that cannot communicate. Only he who has measured the dominion of force, and knows how not to respect it, is capable of love and justice." (Simone Weil, "The Iliad or The Poem of Force," trans. Mary McCarthy [1945], in Simone Weil: An Anthology, ed. Sian Miles [New York: Grove Press, 1986], 192)

There will always be a gap between the supposed Migration Era "Heroic Age" of Beowulf--an age, moreover, with its roots hopelessly tangled between mythos and anthropological reality--and the cultural world of its readers, and perhaps its writer, in ninth or tenth-century Anglo-Saxon England, and this raises the question, posed by John Niles in 1993: "What are the cultural questions to which Beowulf is an answer?" (John D. Niles, "Locating Beowulf in Literary History," Exemplaria 5 [March 1993]: 79). For Niles, this means dispensing with the notion that Beowulf might be able to tell us something about the supposedly static historical reality of fourth to sixth-century Germanic social institutions or "heroic values," and concentrating instead on the ways in which the poem represents a "broad collective response to changes that affected a complex society during a period of major crisis and transformation" (ibid., 81). While I readily agree with this, and even feel what might be called the collective sigh of relief at finally being able to let go of the obsessive desire to know and see the supposedly monolithic past of early Europe through the poem, at the same time I am haunted by the notion that the poet himself, and perhaps even his audience, could not let go of that desire. And, therefore, much of the poem's energy--both aesthetic and social--is a result of the ways in which the poem appropriates the historical and mythological milieu of the earlier Scandinavian culture in order to both propagandize particular Anglo-Saxon values and honor what is perceived to be a vital ancestral heritage, while it also performs the tensions and anxieties--both conscious and unconscious--inherent in such an enterprise.

There is something else, too, that I believe the poet desired, perhaps futilely, albeit with some hope and expectation--he wanted the past, however fallen and collapsed and damned, to speak to his present moment and to be relevant to it. In this sense, the past and its supposed values had to be real, if occasionally puffed into legend, in order that the poet's present moment and world could be seen and felt as the logical culmination of everything that had come before. The poem, therefore, is a kind of inquiry into a collective unconscious and history that consecrates the present, and even authorizes it. James Earl, of course, has illustrated this idea beautifully in his book Thinking About Beowulf (1994), and other scholars have touched upon it in some depth--notably Fred Robinson and Nicholas Howe, among others I don't have time to name here. But there is also the caution, articulated by the historian Dominick LaCapra, that there is a danger in any approach to the past that views that past as some kind of "pure, positive presence," because the past is always "beset with its own disruptions, lacunae, conflicts, irreparable losses, belated recognitions, and challenges to identity" (Dominick LaCapra, History and Memory after Auschwitz [Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998], 24). There will always be a tension, then, in the text of Beowulf, between the poet's desire to body forth his ancestral past as a positive presence and the ways in which the figures of that past do not always stand still within the confines of their conscription. The poem, as an act of cultural memory-making, cannot completely shake off what might be called the traces of a real historical memory, and in fact, it even displays what might be called the repressed after-images of that memory, which ultimately give to the poem, for all its cadences of solemn mourning, an air of hysteria.

There will always be an incommensurability between the ways in which the figures of the past, in Walter Benjamin's words, are always striving by "a secret heliotropism . . . to turn toward the sun which is rising in the sky of history," and the ways in which those in the present are resurrecting the dead only to bury them again with different rites and under a different sky. And this brings us to the question of whether or not there are ethics to be considered in the representation of what might be called a traumatic past, and certainly the past of the poem is traumatic--we might even say it is thoroughly shot through with the chips of apocalyptic, violent time. I believe that the poem itself, on both a conscious and unconscious level, performs the anxiety that attaches to this question of ethics, and also, that its primary plot and subject matter--Beowulf's heroic deeds and also his death struggle--are continually framed by and referred to this very question. There is hardly a moment in the text, in fact, when the characters, and even the poet himself, are not voicing their anxious concern that the past be remembered properly and in a way that is fruitful for the future, while at the same time, the elsewhere ghosts of that past, always mis-recognized until it is too late, are coming to eat them alive.

Emmanuel Levinas has written that history is a collection of instants of time that are always inexorably separate from each other and even exclude one another, and further, the only way to recognize the absolute alterity of an instant of time other than the one we inhabit and experience through our own subjectivity (which weighs us down with the burden of a material self-relationship) is when it comes to us from the "mystery" of the "other person." In Le temps l'autre, Levinas wrote that

The 'movement' of time understood as a transcendence toward the Infinity of the 'wholely other' [tout Autre] does not temporalize in a linear way, does not resemble the straightforwardness of the intentional ray. Its way of signifying, marked by the mystery of death, makes a detour by entering into the ethical adventure of the relationship to the other person. (Time and the Other, trans., Richard Cohen [Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 1987], 33)

But the "other person" can never be our contemporary, and we can not meet "at the same time." Time then, as explained by Levinas's translator Richard Cohen, "is the effect or event of the disjointed conjunction of these two different times: the time of the Other disrupts or interrupts my temporality. It is this upset, this insertion of the Other's time into mine, that establishes the alterity of veritable time, which is neither the Other's time nor mine" ("Introduction," Time and the Other, 12). Most important, we must understand that, for Levinas, this alterity possesses an ethical dimension, and philosophy, which is always rooted in trying to understand the firstness of first philosophy (in other words, the egoist will and autonomy), is always inadequate to the excellency of ethics, and therefore, the Levinasian subject is always "traumatized, loses its balance, its moderation, its recuperative powers, its autonomy, its principle and principles, is shaken out of its contemporaneousness with the world and others, owing to the impact of a moral force: the asymmetrical 'height and destitution' of the Other" (ibid., 15). Further, as Cohen has also written, it is important to recognize that this move whereby the subject is "shaken out" of his own time does not mean he has therefore entered

a wild no man's land where anything and everything is permitted, where thought becomes radically otherwise than thinking, a vertiginous leap toward "action," "dance," or "violence," where the rupture of thought makes all names possible by making them all equally unintelligible; but, as Levinas would have it, to be awakened to an even more vigilant thinking, to a more attentive, alert, sensitive awareness, to a thinking stripped to the rawest nerve, to an unsupportable suffering and vulnerability, a thinking which thinks otherwise than thought itself, because suffering the inversion and election of being-for-the-other before itself. (ibid., 25)

For Levinas, the chief and most excellent work of the subject is to break free from its enchainment with itself through a relationship with the Other, and this is why Hamlet's question--"to be or not to be?--is not the question par excellence, for, as Levinas writes, "the hero is one who always glimpses a last chance, the one who obstinately finds chances" (Levinas, Time and the Other, 73). Furthermore, to enter into a relationship with the Other is to enter, not into an ontological or epistemological history, but rather, into a sacred history. And this sacred history, as Cohen explains

is not the voyage of Odysseus, who ventures out courageously but only in order to finally return home, where he began his voyage; but the journey of an Abram, who leaves his ancestral home for good, who never returns and never arrives at his destination, who encounters and is subject to the absolute alterity of God, who overthrows the idols and is transformed to become his better self, Abraham. (ibid., 24)

And such, also, is Beowulf, who, for all his testosterone-ridden bellowing, is a man ahead of his time. In a period when when most men would have heeded Hygelac's advice to "let the South-Danes themselves work war against Grendel" ("lete Suð-Dene sylfe geweorðan guðe wið Grendel"; ll. 1996-97) and who only boarded their ships for raiding ventures, Beowulf, as Earl has written, "rises above the claims of kindred and sexuality to embrace the more abstract claims of civilization" (James W. Earl, Thinking About Beowulf [Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994], 38). He embraces, moreover, a certain kind of rootlessness that allows him to see that his country is not just Geatland or even Daneland, but the whole world, and in this sense, he is every brother's keeper and loves his neighbor more than himself. But Beowulf is also a murderer who does not always recognize that his enemy is also his neighbor and brother. And therein lies much of the tension of the poem, as well as its unconscious moral force, both for the characters within the narrative as well as for, I imagine, its earliest audiences who could not have helped but feel anxious, as Beowulf himself is anxious, when he enters the dragon's cave, precisely because he knows he will not come back out alive and cannot conceive of any other alternative. And the audience's anxiety would have also centered upon the inescapable historical fact that even though Grendel and his dam, and even the dragon, are dead, their children are ceaselessly at play in the killing fields of history, and further, as the Finn episode illustrates, no matter how much of a deep freeze you place the restless heart of murder into, it still burns. It isn't just, as Hrothgar sermonizes, that death comes for everyone in the end, but rather, that it could come with such violence.

And there is also, perhaps, the anxiety that might stem from the reader's or listener's recognition--conscious or otherwise, that for all the textual space he occupies, Beowulf is not so much the central character of the poem, as he is the interloper at the margins of a story that is less about the redeemer-hero questing for fame and more about the chaos and convulsions of Germanic tribal society--the prehistory, as it were, of the nation-states of post-Conversion England, that was mainly characterized, as James Earl has described England during the period of conquest and settlement, by "military organization, war with native inhabitants, large land claims, power struggles, masculine violence, exploitation and lawlessness" (Earl, Thinking About Beowulf, 37-38). And, as Nicholas Howe has written,

Although he exerts his authority to keep the peace, Beowulf cannot reshape his world of fragmented tribes and kingdoms; he is not a sixth-century Bismarck or even a Charlemagne. Rather, Beowulf holds out some brief hope that the geography of the north need not be demarcated by feuding parties but by beneficent voyagers such as he was as a youth. (Nicholas Howe, Migration and Mythmaking in Anglo-Saxon England [New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989], 173).

I want to suggest, however, that for the original audiences of the poem, the supposedly lawless and violent past might not have felt as past--as collapsed--as the poet might have wanted it to feel, and we might also consider the ways in which the later nation-states of an Alfred or a Charlemagne or a Bismarck themselves eventually convulse and collapse over and over again, giving rise, in the poet's time as well as our own, once again, to factionalism, ethnic hatred, and war, engendered by a certain kind of limiting and isolationist "group think" that sets itself in direct opposition to "state law," and even, through terrorism, thrives on its lawlessness. And this is why the poem's most insistent theme, on an unconscious level, may simply be: ladies and gentlemen, the tribes have not left the building.

It is in Grendel's character, especially, that we have a personification of the unconscious tension in the poem between the idea that a certain kind of sublime human rage is finally dead and the historical fact that it can never really be dead, but rather, only goes underground to reshape itself and then re-emerge later at the time most propitious for its assaults. Grendel's violent assaults against Heorot and its inhabitants, prior to Beowulf's arrival, are described by the poet as a kind of "warfare," or "battle-craft" ("guðcræft"; l. 127) that lasts for "twelve winters' time" ("twelf wintra tid"; l. 147), during which time Grendel would seem to be lashing out against his exile from the company of men and their bright halls (an exile first dictated by God to Cain after Cain's murder of Abel, and imposed upon Grendel due to his status as a descendant of Cain's; ll. 102-14). Perhaps most striking in this conflict is Hrothgar's seeming inertia in the face of such a feud (a feud, moreover, that threatens the very fabric of the social world he has built up and "held" for half a century), as well as the cowardice of the men who seek a bed elsewhere than in the great hall when it is feared or "betokened" ("gebeacnod") that Grendel will be nearby (ll. 138-143), and one explanation for this may be that Grendel is so demon-like ("ellengæst," or "powerful ghost" and "ellorgæst," or "elsewhere ghost"; hence, alien, terribly strange, and not human) that Hrothgar and his men are incapable of knowing how to fight him—Grendel, as well as his muscular (yet also mysterious) hatred, therefore, exceed the boundaries of what is "knowable" in this culture, and thus there is no logical means of fighting him that can be readily seized upon by Hrothgar and his men, and Grendel is immune to their swords. But Grendel's "feud," which is essentially fratricidal, is knowable in the South-Danes' culture, and one could even say that Hrothgar's hall is both built up and torn down simultaneously within the crucible of that culture's tribal feud and vengeance, of which Grendel is simply a cultural marker, if not the very manifestation of its collective Unconscious, and this may be why, at one point, Grendel is referred to as a "hateful hall-thane" ("healðegnes hete"; l. 142), and Hrothgar even refers to him once as "my invader" ("ingenga min"; l. 1776). Perhaps Grendel's most important description in relation to this point is when Hrothgar tells Beowulf that Grendel has been seen walking along the road "on weres wæstmum" ("in the shape of a man"; l. 1352), indicating that while Grendel's hatred is perceived to be primeval and almost non-human, his shape is readily recognizable.

The multiplicity of descriptions of Grendel within the poem, from ellengæst ("strong spirit"; l. 86) to healðegnes hete ("hateful hall-thane"; l. 142) to æglæca ("terror"; l. 159) to deogol dædhata ("secret hatemonger"; l. 275)—just to name a few—points to Grendel's inherently ambiguous nature within the South-Dane, and more broadly, the poem's heroic culture that is desperately trying to come to grips with his presence, at once strange and terrifying, but also familiar. By virtue of his association with Cain, he is both human yet pathological; because he comes from the land of giants, he is also otherworldly, misbegotten, both alive and dead at once. And yet, he is also the "stranger-guest" to whom hospitality is never offered or even thought. In the struggles between Grendel and Heorot we can see the tension that inheres when different modes of "remembering" meet each other on the plain of history: the South-Danes do not recognize themselves in the outcast Grendel, who has come from the "no man's" borderland of their prehistory and therefore represents what is supposedly lawless and inhuman (read: uncivilized) there, yet Grendel rages against the edict that he can have no place with the men in Heorot where, we can assume, he feels he belongs, as kin, otherwise he would not suffer so much when hearing the "joyful" celebrations from inside the hall (ll. 86-90).

Grendel's encounters with the South-Danes then, both prior to and after Beowulf's arrival in Heorot, represents a rupturing of a particular historical continuum--the uncivilized (hence, to the South-Danes, the anthropologically primitive) Grendel blasts a hole in sixth-century South-Dane time and literally tears his way, cannabilistically, through Hrothgar's troop of soldiers, who are therefore consumed by the literal mouth of their own forgotten (or repressed) history. And this may be the same mouth that ultimately takes Beowulf in its jaws, for when it is clear in his battle with the dragon that his defenses are weakened, the dragon "seizes him by the neck in his bitter jaws" ("heals ealne ymbefeng biteran banum"; ll. 2691-92), and although Beowulf continues to flail away at the dragon with his sword and even succeeds, with Wiglaf's help, in killing the creature (ll. 2702-11), the dragon's bite constitutes his mortal wound. But even if Beowulf cannot escape the jaws of his own violent history, it has to be noted that he is the one character in the poem most sensitive to what it would mean to enter into "the ethical adventure" of confronting the "asymmetrical 'height and destitution' of the Other," which is why he understands, more than anyone else, that Grendel can only be dealt with in hand-to-hand combat and you don't bring an army to fight a dragon. Beowulf recognizes, moreover, the responsibility implicit in being "shaken out" of his contemporaneousness with his own time and world in his encounters with Grendel, and also with Grendel's dam and dragon--the Other must be met "face-a-face sans intermediare," and this "facing," as Levinas terms it, "is always an extradition without defense or cover," and also a "nudity" which exposes the hero to his own death. And so, Beowulf plunges himself into both water and fire--the "mediums," as it were, of the "wholly Others" of the poem--to face the mysterious strangers, because he believes, like Alyosha Karamazov in Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, "We are all responsible for everyone else--but I am more responsible than all the others."

It has to be noted that Beowulf does not recognize Grendel, however, as a fellow-creature for whom he is also responsible, except to relieve him of his miserable angry existence. He does not recognize, moreover, that the same subjections that press upon the spirits of himself and his men also press upon Grendel and cause him to suffer, and therefore, there is no means, for Beowulf, of even conceiving of what it might mean to live alongside a Grendel, except in a state of war. Nevertheless, Beowulf, even in the face of his own death, is always restless in his desire to be always coming, rather than going, and in this respect, he is the true ethical hero for whom, paraphrasing Levinas, death is not the limit of idealism. Further, Beowulf dies expressing his grief at having no son upon whom to bestow his war-gear ("Nu ic suna minum syllan wolde guðgewædu, þær me gifeðe swa ænig yrfeweard æfter wurde lice gelenge"; ll. 2729-32), which is essentially, a desire for transcendence, and also, to keep fighting the good fight. It is also a gesture, following Levinas, that signifies the desire for fecundity, in which "paternity is not simply the renewal of the father in the son and the father's merger with him, it is also the father's exteriority in relation to his son, a pluralist existing" (Levinas, Time and the Other, 92).

I want to conclude by suggesting that when we read Beowulf, something happens that is not possible in real historical time: the "alterity of veritable time"--neither wholly Grendel's nor wholly Beowulf's time, neither wholly early Scandinavian nor wholly later Anglo-Saxon time, neither wholly the historical Other's time nor wholly our own time--this time comes into legibility in what Earl has called "the world of the poem," and makes Levinas's "ethical adventure of the relationship to the other person" briefly possible. In the character of Beowulf we can glimpse a kind of Levinasian hero whose relationship with the Other--whether the Danes or Grendel or those whom he imagines remembering him in the future--is essentially, as Levinas has written, "a relationship with a Mystery" in which "the other's entire being is constituted by its exteriority" (Levinas, Time and the Other, 75-76). In Beowulf's final command--that a memorial bearing his name be built high on the whale-cliffs where it can be seen by traveling seafarers--we have a gesture that calls to mind Levinas's erotic caress of the future, in which the hero, just prior to death, always glimpses a last chance. And this caress is erotic, not because, following Freud, it is a "grasping" or "possessing" that seeks power over the Other through fusion, but because, in the more radical way Levinas defines it, it is a reaching out toward what is always "about to come" ("a venir") and which the ethical hero recognizes he cannot actually touch, yet reaches for anyway. It is the heroic gesture par excellence--a reaching through death toward life--that signifies the desire to be with the Other in the future in a voluptuousness of Being.