Eileen A. Joy, Assoc. Professor

Department of English Language and Literature

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

ejoy@siue.edu

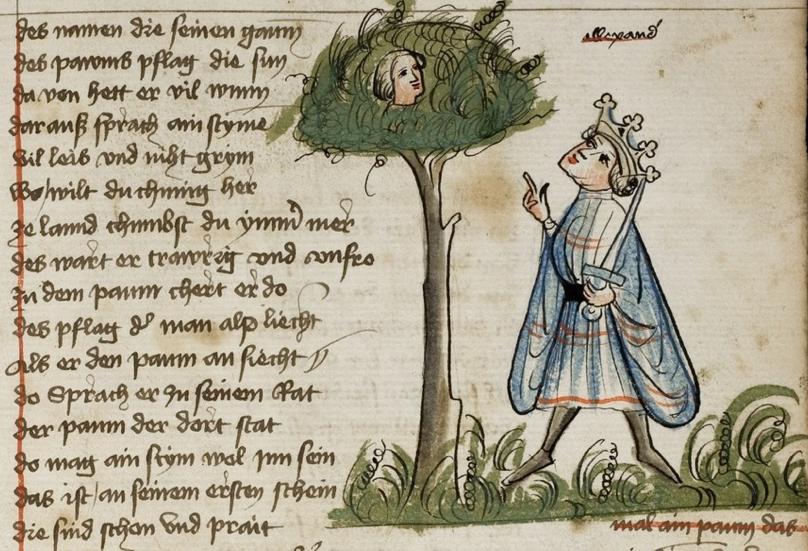

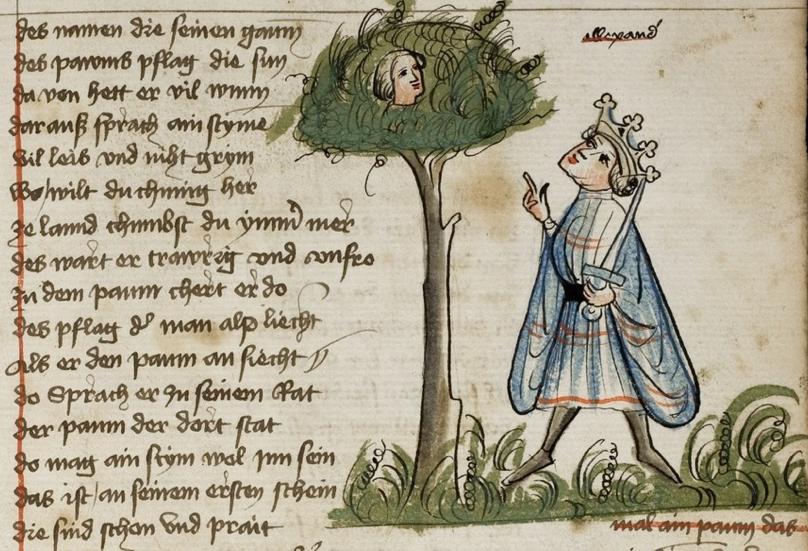

Figure 1. Alexander with the oracle of the Tree of the Sun

Literature and Identity Formation: An Interdisciplinary Symposium

Center for Canon and Identity Formation (CIF)

University of Copenhagen

20-21 May 2011

Paper Abstract:

I Have Given Up Trying to Recognize You in the Surging Wave of the Next Moment: The Old English Letter of Alexander to Aristotle as a System in Cascade

You who never arrived

in my arms, Beloved, who were lost

from the start,

I don't even know what songs

would please you. I have given up trying

to recognize you in the surging wave of the next

moment. All the immense

images in me—the far-off, deeply-felt landscape,

cities, towers, and bridges, and unsuspected

turns in the path,

and those powerful lands that were once

pulsing with the life of the gods—

all rise within me to mean

you, who forever elude me.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, “You Who Never Arrived”

In some contrast to the Alexander of other Old English texts adapted from Latin sources, such as the Orosius—where Alexander is described as se swelgend (according to Bosworth-Toller, ‘voracious person’ or ‘glutton,’ but also, more fittingly in this case, ‘a place which swallows up, a very deep place, an abyss, a gulf, a whirlpool’)—the Alexander of the Letter, traveling through “India,” seems primarily intent on ‘beholding’ [sceawigað] the spectacle of ‘wondrous creatures’ [wunderlice wyhta] as well as searching for that which is most “unknown” [uncuð] and “interior” [innanwearde, ‘innermost part’], rather than seeking slaughter and conquest. Given that the ostensible pretext of the letter is to provide data to a former teacher so that, as Alexander himself puts it, Aristotle’s wisdom and learning “might contribute to a certain extent to the understanding of these novelties,” it makes sense that the Alexander of this letter is more of an explorer-naturalist than a military general, although various military campaigns are undertaken along the way.

At the same time, the one military campaign to which the Letter devotes the most space—Alexander’s supposed conquest of Porus, king of Fasiacen—is an extremely slippery affair, and it is not at all clear that Alexander conquers King Porus at all, although early on, Alexander claims to have “overcome and conquered” [ofercwomen 7 oferswyðon] him, and to have taken “his entire nation under control.” Yet in almost the same breath he shares his desire to see the “innermost part” of India and to travel there by the “dangerous paths and ways” so that he can catch up with Porus “before he could escape into the deserted tracts of the world.” And a bit later in the Letter, after Alexander has traveled further and further by these most “dangerous” routes, he mentions that he and his men “came to the land and the place where Porus the king was encamped with his army.” Porus, in this second encounter, after a ruse in which Alexander goes to his camp, pretending to be an “ordinary man” seeking wine and food, ultimately gives himself and his army freely into the hands of Alexander, who promptly repays the favor by giving Porus his kingdom back, in return for which Porus gives to Alexander all of his treasures and also erects in gold two statues of Hercules and Bacchus at “the eastern edge of the world,” to which Alexander promptly makes sacrifices. Here, the usual tropes and images of clash and battle and wholesale slaughter give way to a fluid exchange of goods and identities and nations along the edge of an East that is itself all edges and shifting frontiers.

This paper will argue that, in seeking to both penetrate the “innermost part” of India as well as to overcome his enemies (whom he never really overcomes—indeed, the oracle of the holy tree of the sun reveals to him that he will soon be betrayed by a close intimate and never return home; further, the “wonders” he seeks are often withdrawing into hiding places), the Alexander of the Old English Letter is himself penetrated and overcome, and following a recent argument by Susan Kim,[1] by his own pen, even. In the act of writing the letter itself, Alexander opens himself to the scene of writing as the scene of his own dissolution and also opens up new modes of intra-subjectivity that were perhaps not readily available by other means to the Anglo-Saxon reader. In addition, the Letter reveals an heroic identity that, in contrast to the heroic identity exemplified in other Old English works such as Beowulf and Battle of Maldon, is not singular, hard-edged, and monolithic, but rather is dispersed and distributed across a fluid network of agents, human and nonhuman, enmeshed with each other in a vast “middle” space that has no real boundary points, no beginning or end. Identity in the Letter thus constitutes a series of relay traces across this middle space that are enabled, but never entirely settled by, writing. Although Alexander’s ostensible aim in his letter, as well as in his military and other campaigns, may be to fashion himself as a sort of supra-body and supra-mind for whom the world is a conquerable and contained object of his doing and knowing, and while the Old English translator of the Latin exemplar may have wished (as Andy Orchard has argued)[2] to further augment Alexander’s status in Anglo-Saxon England as a moral exemplum of heroic pride run terribly amok, the asymmetrical trajectories, encounters, and events of the Letter itself reveal that identity, whether self-described or represented from some place outside the subject in question, is always ontologically unstable and indeterminate. Ultimately, in the Letter, “Alexander” is not so much an identity at all, but rather, a polyphony, what Julian Yates, following Michel Serres,[3] has termed “agentive drift,” where agency is “a dispersed or distributive process in which we participate rather than as a property which we are said to own,” and where “being human” is “to be dependent, to be an intermediary, a go-between, to be one thing among many, inhabiting a system in cascade.”[4]

Endnotes

1. Susan M. Kim, “‘If One Who Is Not Is Not Present, A Letter May Be Embraced Instead: Death and the Letter of Alexander to Aristotle,” JEGP 109.1 (2010): 33-51.

2. Andy Orchard, “The Alexander Legend in Anglo-Saxon England,” in Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), 116-139.

3. Michel Serres, The Parasite, trans. Lawrence R. Schehr (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982).

4. Julian Yates, “Towards a Theory of Agentive Drift; Or, A Particular Fondness for Oranges circa 1597,” parallax 8.1 (2002): 48, 50 [47-58].