Chapter 10

Exteriority Is Not a Negation But a Marvel: Hospitality, Terrorism, Levinas, Beowulf

Eileen A. Joy

[copy of a book chapter in Cultural Studies of the Modern Middle Ages, ed. Eileen A. Joy, Myra J. Seaman, Kimberly K. Bell, and Mary K. Ramsey (Palgrave Macmillan, Dec. 2007)]Abstract: This essay considers Emmanuel Levinas's philosophy of hospitality in relation to the "isolated and heroic being that the state produces by its virile virtues," through an analysis of female Chechen suicide terrorists in contemporary Russia and the figure of Grendel in the Old English poem Beowulf, in order to raise some questions about the relation between violence, justice, and sovereignty, both in the Middle Ages and in our own time.

He who does not realize to what extent shifting fortune and necessity hold

in subjection every human spirit, cannot regard as fellow-creatures nor love

as he loves himself those whom chance has separated from him by an abyss. The

variety of constraints pressing upon man give rise to the illusion of several

distinct species that cannot communicate. Only he who has measured the dominion

of force, and knows how not to respect it, is capable of love and justice.

—Simone Weil, "The Iliad, or The Poem of Force"

Prolegomenon: Beyond the State in the State

In Adieu to Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida argues that Levinas's philosophy, especially in Totality and Infinity, has bequeathed to us an "immense treatise of hospitality." According to Derrida, although "the word 'hospitality' occurs relatively seldom in Totality and Infinity, the word 'welcome' is unarguably one of the most frequent and determinative words in that text."[1] At the very outset of Totality and Infinity, Levinas writes about the Other as the "Stranger [l'Etranger]. . .who disturbs the being at home with oneself [le chez soi]."[2] In the wake of this disturbance, the ethical subject "is incapable of approaching the Other with empty hands," and by way of "conversation" she welcomes the Other's "expression, in which at each instant he overflows the idea a thought would carry away from it."[3] The welcoming [accueillance] of the expression of the stranger-Other is a welcoming of a teaching [enseignement] that "comes from the exterior" and in which "the very epiphany of the face is produced."[4] This is a "face" that is not a material face, per se—the specific physical visage of a specific person—but is, rather, an "exteriority that is not reducible. . .to the interiority of memory," an expression of being that "breaks through the envelopings" and façades of material form, exceeds any possible preconceptions, and calls into question the subject's "joyous possession of the world."[5] At the same time, because "the body does not happen as an accident to the soul," the physical face is the important "mode in which a being, neither spatial nor foreign to geometrical or physical extension, exists separately." It is the "somewhere of a dwelling" of a being—of its solitary and separated being-with-itself.[6]

While Levinas describes the home, or dwelling, as a site of inwardness [intimité], from which the subject ventures outside herself (and therefore, the real home is always a rootless, wandering mode of being), he also points out that this inwardness "opens up in a home which is situated in that outside—for the home, as a building, belongs to a world of objects."[7] The home possesses two facades, and, thereby, two positions, for it "has a 'street front,' but also its secrecy. . . .Circulating between visibility and invisibility, one is always bound for the interior of which one's home, one's corner, one's tent, one's cave is the vestibule."[8] The home, then, is both the architectural site filled with material furnishings [Bien-meubles, or movable goods ] that, by its very nature, is "hospitable to the proprietor," as well as the site of interiority in which the subject withdraws from the elements and can "recollect" herself.[9] Recollection [recueillance], for Levinas, is a kind of "coming to oneself, a retreat home with oneself as in a land of refuge, which answers to a hospitality, an expectancy, a human welcome." This is, in essence, a kind of self-possession made possible by the subject possessing a home in which she is able to be welcomed to herself, which welcoming constitutes the condition by which a certain affection for herself is "produced as a gentleness that spreads over the face of things" and makes the welcome of the stranger-Other possible.[10]

As a result, the ethical self is also a "sub-jectum; it is under the weight of the universe, responsible for everything. The unity of the universe is not what my gaze embraces in its unity of apperception, but what is incumbent on me from all sides. . .accuses me, is my affair.”[11] The "I" is ultimately the "non-interchangeable par excellence" and also "the state of being a hostage," and it is only "through the condition of being hostage that there can be in this world pity, compassion, pardon and proximity." Even more pointedly, Levinas writes, "the word I means here I am, answering for everything and everyone," and we are always summoned "as someone irreplaceable."[12] Levinas's philosophy of the ethical relation to the stranger-Other poses a stern (and perhaps wildly unrealizable) political imperative, for, as Levinas himself puts it, "the first, fundamental, and unforgettable exigency of justice is the love of the other man in his uniqueness."[13]

In Derrida's view, Levinas's ideas regarding the welcoming of the enigmatic face of the stranger-Other is a type of hospitality that is "not simply some region of ethics" or "the name of a problem in law or politics: it is ethicity itself, the whole and the principle of ethics."[14] More importantly, Levinas's "infinite and unconditional hospitality" raises the difficult question of whether or not Levinas's philosophy "would be able to found a law and politics, beyond the familial dwelling, within a society, nation, State, or Nation-State."[15] How would such an ethics be "regulated in a particular or juridical practice? How might it, in turn, regulate a particular politics or law? Might it give rise to—keeping the same names—a politics, a law, or a justice for which none of the concepts we have inherited under these names would be adequate?"[16] How, also, might Levinas's thought be seen as a provocation to "think the passage between the ethical. . .and the political, at a moment in the history of humanity and of the Nation-State when the persecution of all of these hostages—the foreigner, the immigrant (with or without papers), the exile, the refugee, those without a country, or State, the displaced person or population (so many distinctions that call for careful analysis)—seems, on every continent, open to a cruelty without precedent "?[17]

In Derrida's view, Levinas, through "discreet though transparent allusions. . .oriented our gaze toward what is happening today," to the call of "the refugees of every kind. . .for a change in the socio- and geo-political space."[18] One could even say that present crimes against humanity actually intensify the urgency of Levinas's voice on the matter, and we might also ask how Levinas's hospitality marks (or opens) an important door [porte] into a dwelling that must ultimately be "beyond the State in the State"?[19] Levinas touches upon the question in his conclusion to Totality and Infinity, where he writes that "[i]n the measure that the face of the Other relates us with a third party, the metaphysical relation of the I with the Other moves into the form of a We, aspires to a State, institutions, laws, which are the source of universality. But politics left to itself bears a tyranny within itself; it deforms the I and the other who have given rise to it, for it judges them according to universal rules, and thus as in absentia."[20] Although the individual ethical subject is ultimately made invisible by the state's insistence on "universality," and therefore hospitality has to define itself, in certain singular situations, against the state, the state nevertheless reserves a framework for it (through various of its institutions, such as citizenship and law courts and bills of rights), and also operates as a placeholder of borders that will need to be transgressed in order for true ethics to be possible. Although the democratic state, in Levinas's view, can function as a rational political order that ends exile and violence and endows men with freedom, the world in which the welcoming of the stranger-Other is possible will always be radically different from the state, which, "with its realpolitik, comes from another universe, sealed off from sensibility, or protest by 'beautiful souls,' or tears shed by an 'unhappy unconsciousness.' "[21] There is a necessity for a type of politics that purposefully forces open a door [porte] in the place that marks the border between the enclosure of the state and the more perfect future that lies beyond it, and this politics is often accomplished, in different times and places, by what Levinas calls the "isolated and heroic being that the State produces by its virile virtues. Such a being confronts death out of pure courage and whatever the cause for which he dies."[22]

What I offer in this essay is a consideration of Levinas's philosophy of hospitality in relation to that "isolated and heroic being that the State produces by its virile virtues," through an analysis of the ethical "problem" of terrorism in the separate cases of female Chechen suicide bombers in contemporary Russia and Grendel in the Old English poem Beowulf. In the trauma that is created in the wake of disturbance of the violent, destroying stranger-Other—such as a Grendel or a suicide terrorist—how is welcoming, or hospitality (the very foundation of ethicity), even possible? If the actual, material face is the "somewhere of a dwelling" of the stranger-Other whom we must welcome, how do the faces of those who have been determined ahead of time to be too exterior (read: too foreign or inhuman) forbid, yet also call more urgently for our welcoming of them? If the home constitutes the site of recollection (a coming-to-oneself) that is the condition for welcoming (a going-out-of-oneself to the Other), what happens to the ethical project of hospitality when the stranger-Other is actively trying to destroy that home (perhaps out of anomie, but also rage, over his or her own homelessness)? If, as Levinas argues, the "positive deployment of a pacific relation with the other, without frontier or any negativity, is produced in language,"[23] how can we make peace with those to whom we refuse to speak, and who, in turn, refuse to speak to us? In what way does terroristic violence (whether the anthrophagy of a Grendel or the belted bomb of a suicide terrorist) simultaneously summon and accuse us as those who are irreplaceable? How, finally, do these terroristic figures signify and enact a type of violence (even, a type of radical evil) that the state itself simultaneously exercises and punishes?

Most likely written in a tenth- to eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon monastic setting[24] that would have been structured by a Christian ethics of hospitality, and taking as its subject an earlier, proto-Christian cultural milieu (Scandinavia in the geardagum, ' old days' ) that was also structured, in important ways, by particular socially regulated modes of hospitality, Beowulf reveals many of the fissures that often open up when the moral dictums, "welcome the Stranger" and "love thy neighbor as thyself," run up against the troubling socio political question, "what if the Stranger, or my neighbor, is also my enemy?" The dead bodies of Chechen women who have killed themselves and others in the course of their suicide missions within Russia pose the same troubling question and also serve as placeholders of Levinasian "faces" that, because they are both vulnerably and nakedly human but also enclose a terrifying will-to-death, challenge our ability to welcome the expressions of what we believe are the radically exterior beings concealed within. In the same way, the disfigured (and monstrous) yet still human form of Grendel, whom Beowulf describes as an uncuðne nið [unknown violence] (276),[25] both refuses all gestures of welcoming and recollection, while also calling into question the limits of the ethics (and even, the law) of hospitality that were clearly important in both Anglo-Saxon England and in the world of the poem. Indeed, Grendel's presence, both as aggressive intruder, and later, as displayed body pieces (severed shoulder and head), inside the ceremonial dwelling of the great hall of Heorot points to a certain violent displacement and dispossession that seems intrinsic to the guest-host relationship, especially in the world of a poem where almost all of the violent episodes—between men and monsters, but also between men and men—happens within the walls of spaces, whether halls or caves, designated as home. As John Michael has written regarding the current "war on terror" and Derrida’s writing, by way of Levinas, on hospitality, "If the guest has power over the host, the power of a dangerous and perhaps impossible ethical demand, no one can ever be at home anywhere."[26]

I do not wish, at any point in this essay, to imply that there is a one-to-one correlation between the female Chechen suicide bombers and Grendel, for their "cases," as it were, are very different: the former are real persons situated in a very real and troubling contemporary history, whereas Grendel is a fictional bogeyman situated in a pseudo-historical, medieval text. And whereas the political crisis and motives of the suicide bombers can, without too much trouble, be well articulated, Grendel is a figure who appears to come from nowhere bearing an inscrutable hatred. But as figures bearing terroristic violence, they both pose a certain challenge to societies that claim not to know them nor to understand their aggression (or both). At the same time these societies are themselves caught up in cycles of aggression and murder for which they have devised legalistic and other justifications, yet terrorism, for these societies, is always supposedly prohibited and can only ever come from the outside. Both the suicide bombers and Grendel engage in forms of supposedly extralegal force that frustrate the very self-identity of societies that consider themselves "just" or "right," and that either see no remedy under their laws for these terrifying invaders, or will not admit the possibility of one. While both the Chechen women and Grendel are viewed in their respective cultures as figures of exorbitant exteriority, nevertheless, they are mainly terrifying for the ways in which they bring to vivid life (and death) the obscene violence at the interior heart of states that mark the places of supposedly more ethical communities . Finally, through their ferocious aggression—which aggression, I would argue, is born out of particular historical moments as a kind of structural excess—both the Chechen women and Grendel perform what Levinas calls a "deadly jump" [salto mortale] over the abyss that separates the present from death, and thereby enter the horizon of the "not-yet," which is "more vast than history itself" and "in which history is judged."[27]

It Gleams Like a Splendor But Does Not Deliver Itself

In Levinas's philosophy, "being-for-the-other" posits the possibility of transcending the burden of self and ego through a face-to-face relationship—what Levinas terms la face-à-face sans intermediare, "a facing without intermediary"—with the Other, who, "under all the particular forms of expression where the Other, already in a character's skin, plays a role—is. . .pure expression, an extradition without defense or cover, precisely the extreme rectitude of a facing, which in this nudity is an exposure unto death: nudity, destitution, passivity, and pure vulnerability."[28] Further, this "pure expression" always exceeds any figurative limits we might put on it—"Expression, or the face, overflows images."[29]

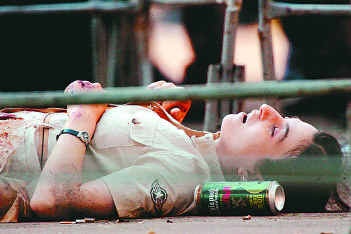

Even though I know that, in Levinas's scheme of things, the face is not really a face, per se, but rather an expression that exceeds figuration, I have thought, obsessively, about the face of Zulikhan Elikhadzhiyeva, the twenty-year-old Chechen woman who approached the admissions booth of an outdoor rock festival at Moscow's Tushino airfield on 5 July 2003 and detonated the explosives strapped to her belt, killing only herself (another female bomber who was with her managed to kill herself and fourteen others).[30] Browsing the Internet one day searching for pictures of this event, partly due to my curiosity about the phenomenon of women who are suicide terrorists, I came across a photograph of Elikhadzhiyeva lying on her back between police barricades, blood splattered on the bottom edges of her shirt, one fist partially clenched over her heart, a beer can overturned on the ground beside her head, her eyes closed, her mouth half-open—the scene is almost peaceful, and her face, serene, if also vulnerable.[31]

I could not get Elikhadzhiyeva's face out of my mind when I first saw it, nor can I, even now. Elikhadzhiyeva's face haunts me precisely because it is what Levinas would have said is not really a face, but a facade, "whose essence is indifference, cold splendor, and silence," and in which "the thing which keeps its secret is exposed and enclosed in its monumental essence and in its myth, in which it gleams like a splendor but does not deliver itself."[32] While there are some, I know, who will claim that it is not possible to be captivated (which is to say, to be struck with wonder) by such a face, the possessor of which is a suicide bomber (whom we call a monster and for whom some will argue no empathy is possible or even required), I would argue that, at the very least, this face—which is extraordinary in its exteriority—is a marvel that commands our attention and challenges us to take on the task, in Levinas's words, of responding "to the life of the other man," for we "do not have the right to leave him alone at his death."[33]

Between October 2002, when roughly forty Chechen rebels, including over a dozen women, seized a theater in Moscow in the middle of a musical performance and held 800 theatergoers hostage, and September 2004, when more than a dozen Chechen rebels, also including women, seized a school in Beslan (in the southern republic of North Ossetia), Chechens and Russians have witnessed the emergence of what many consider to be a shocking phenomenon—female suicide bombers.[34] Because many Chechens reject the idea that these women have embraced a radical Islamic fundamentalism, and many Russians, conversely, have assumed that these women embody what they see as the "Palestinianization" of the Chechen rebellion,[35] a certain tension, confusion, and even hysteria attaches to the ways in which ordinary Russians and Chechens, government officials, and the international press have attempted to describe them. It has been said about the female Chechen suicide bombers, alternatively, that they have been kidnapped by Islamic extremists, given psychotropic drugs, and then raped as part of their coercion into doing what no woman would supposedly do of her own accord;[36] that they are emotionless "brick walls," "pre-programmed," "brainwashed," and "de-humanized";[37] that they are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder;[38] that they are blackmailed "zombies";[39] and that they are the harbingers of the fact that "something has come unglued at the heart of Chechen society."[40]

Standing in stark opposition to the idea that the female bombers are somehow not in their right mind, or that they have been coerced against their will, are the statements of the women themselves, or of those who might have known something about their motives. In September 2003, an anonymous Chechen woman (going by the pseudonym "Kowa") told a BBC World Service reporter, "I have only one dream now, only one mission—to blow myself up somewhere in Russia, ideally in Moscow. . . .To take as many Russian lives as possible—this is the only way to stop the Russians from killing my people. . . .Maybe this way they will get the message once and for all."[41] A surviving hostage of the of the Chechen rebel takeover of the Dubrovka Theater in Moscow in October 2003 told an Associated Press reporter that one of her female captors, whose husband and brother had been killed in the war with Russia, said the following: "I have nothing to lose, I have nobody left. So I'll go all the way with this, even though I don't think it's the right thing to do."[42] Speaking of one of the first female Chechen suicide bombers, Elza Gazuyeva, who in November 2001 killed herself and a Russian commander who she believed had ordered the execution of her husband, a woman interviewed in Grozny said of Gazuyeva, "She was, is and will remain a heroine for us."[43] Lisa Ling, who traveled to Chechnya in order to interview families of female suicide bombers for a National Geographic documentary on the subject, said in an interview that the female bombers "were normal girls" who, nevertheless, also "saw no way out. They saw their lives. . .as too difficult to handle, and when they reached that stage, in their minds, taking out the enemy was an opportunity to become a hero."[44]

It is important to understand the larger historical context within which Elikhadzhiyeva and other Chechen women have committed themselves to murder and suicide—a context, moreover, that can be seen as conducive to, simultaneously, inhumanity, insanity, and the completely rational (and sane) desire for a revenge that could only be accomplished extralegally. Since 1999, when Russia reintroduced military forces into Chechnya in order to suppress the Chechen rebellion (a rebellion they had "put down" once before with massive bombing and other war campaigns in 1994 and 1995), but especially after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, when Russian president Valdmir Putin declared that the struggle against Chechen rebels was simultaneously a struggle against al-Qaeda-sponsored terrorism,[45] Chechen citizens have been plunged into a nightmarish cycle of vicious abuse, including abductions, torture, rape, assassination, and mass extermination. Of particular concern to international human rights organizations have been the systematic "sweep" operations and nighttime raids, on the part of the Russian military, that have resulted in the "disappearance" (likely after torture and extrajudicial execution) of thousands of Chechens since 1999.[46] According to a Human Rights Watch "Briefing Paper" on the subject published in March 2005, the Russian government "contends that its operations in Chechnya are its contribution to the global campaign against terrorism. But the human rights violations Russian forces have committed there, reinforced by the climate of impunity the government has created, have not only brought untold suffering to hundreds of thousands of civilians but also undermined the goal of fighting terrorism." In addition, "as part of Russia's policy of 'Chechenization' of the conflict, pro-Moscow Chechen forces have begun to play an increasingly active role in the conflict, gradually replacing federal troops as the main perpetrators of 'disappearances' and other human rights violations." [47] Most of the "disappeared" are men between the ages of eighteen and forty, although children and women have also been targeted, and although local and federal prosecutors routinely investigate abductions reported by families of the victims, no actual convictions have ever resulted from these investigations. According to Human Rights Watch, most of the cases "are closed or suspended after several months 'due to the impossibility of establishing the identity of perpetrators,' " and even "when detainees held in unacknowledged detention are released and the perpetrators established, no accountability process takes place."[48] There has also been evidence of Russian military forces burying executed Chechens in mass graves.[49] So, while on the one hand, the state, in the form of local and federal government authorities, is "investigating" the abductions and extrajudicial executions of Chechen citizens, with the other hand, in the form of its military, it is burying the evidence of the murder of its own citizens. To add to the general terror and despair of all this, the 2005 "Briefing Paper" also notes that in Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, "most people. . .live in the partial ruins of apartment buildings damaged by relentless bombing campaigns. There is no running water and power outages are frequent." In other areas, people "who have survived the chaos of two wars and actively protested the abuses perpetrated in their villages are now to terrified to open their door even to their neighbors."[50] Such is the bleak world in which Elikhadzhiyeva and other female suicide terrorists were formed.

It has to be admitted that suicide terrorists do not play fair, since, as Jean Baudrillard writes, "they put their own deaths into play—to which there is no possible response ('they are cowards')," but they are also attempting to contest a system "whose very excess of power poses an insoluble challenge," to which "the terrorists respond with a definitive act that is also not susceptible of exchange."[51] In turn, the government's response is typically one of complete refusal to negotiate and flat-out extermination. After the siege at the school in Beslan, Putin told the press, "We shall fight against them, throw them in prisons, and destroy them."[52] Putin's comments are typical of most state governments' responses to terrorists. In April of 2004, in a speech delivered in Kansas City, Missouri, that referred to terrorist attacks in the cities of Karbala, Najaf, and Baghdad in Iraq, Vice President Dick Cheney stated, "Such an enemy cannot be deterred, cannot be contained, cannot be appeased, or negotiated with. It can only be destroyed. And that is the business at hand."[53] On both sides, this is a zero –sum game, and it also raises the difficult question posed by Derrida: "What difference is there between, on the one hand, the force that can be just, or in any case deemed legitimate (not only an instrument in the service of the law but the practice and even the realization, the essence of droit), and on the other other hand the violence that one always deems unjust? What is a just force or a non-violent force?"[54] Because the current government of Russia, and the United States, whatever evidence to the contrary, do not identify themselves as tyrannies, but rather, as progressive democracies that supposedly set certain limits to the government's use of force, terrorism—in particular, suicide terrorism—poses a special problem, because the perpetrator cannot be brought to court. And yet, suicide terrorism—at least, in the case of the female Chechens—can sometimes be a violence of desperate last resort.[55] It does not represent the first time the stranger-Other, who is also a citizen, has knocked on (or blown open) the door of the state and demanded recognition.[56] And in the case of Chechnya, especially, where the perpetrators of abuse against civilians, in "the vast majority of cases. . .are unquestionably government agents,"[57] the avenue of legal recourse for redress of abuses against civilians is obviously not open, except as an apparition.

We must never forget that terrorists are real persons with real lives grounded in all the material and psychic particularities of the local—Zulikhan Elikhadzhiyeva, for instance, lived with her sister in a brick house in a small Chechen village and studied at the medical vocational school there.[58] The two Chechen women, Amanat Nagayeva and Satsita Dzhbirkhanova, who brought down two Russian passenger planes in August 2004, killing themselves and eighty-nine other passengers, lived with two other women in a cramped, bombed-out apartment building in Grozny and worked selling clothing and other goods in the central market.[59] In his study My Life Is a Weapon, Christoph Reuter writes that suicide attackers "are not cruise missiles on two legs, killing machines who come out of nowhere with the wrath of God or the murderous orders of a cult leader programmed into them. They are, whatever lengths they or we will go to forget it, people—individuals with families rooted in a given society."[60] The Chechen women who have become suicide bombers have been living in conditions of absolute poverty and desolation—both physical and psychic—and their acts of terrorism can be seen as the last gestures of an extreme desperation. But we cannot forget that these gestures are also immoral acts of violence that maimed and killed others who were, like the female bombers themselves, "ordinary civilians."[61]

Just as "we" refuse to negotiate with terrorists—just as we withhold, in other words, the gift of welcoming through language—"they" also refuse to welcome us through language, and instead, write their suicide letters on our collective body with their weapons and render us incapable of returning anything to them except our hatred, which they do not stay to receive. But our understanding of these women, if we are willing to embark on such a project, will have to begin with an understanding of the general perception of them, grounded in the order of the symbolic, as monsters. As Jeffrey Cohen reminds us, the monster's body is always a cultural body: "The monster is born. . .as an embodiment of a certain cultural moment—of a time, a feeling, and a place. The monster's body quite literally incorporates fear, desire, anxiety, and fantasy (ataractic or incendiary), giving them life and an uncanny independence."[62] In his "seven theses toward understanding cultures through the monsters they bear," Cohen argues that the monster always embodies difference writ large (usually along lines that are sexual, racial, and cultural), and "the boundaries between personal and national bodies blur" in the body of the monster, which always threatens "to fragment the delicate matrix of relational systems that unite every private body to the public world."[63] The female Chechen suicide bombers are especially troubling in this scenario because they bring together in their cultural bodies two "signs" that have traditionally terrified through their Otherness: "woman" and "nonwhite" (what Cohen terms, following two popular horror films from the 1950s, She and Them!).[64]

Also central to the issue of what might be called the troubling, yet intimate alterity of these women is the name given to them, as a collectivity, by the Russian government and broadcast widely by the international press: they are the "black widows" of Chechnya—that is to say, they are the actual widows (the wives, yes, but also the mothers, sisters, and daughters) of men killed in an ongoing war with Russia that has claimed over 100,000 lives; they are also venomous black widow spiders who kill with one bite. Apparently, the Chechen women first earned this moniker during the rebel takeover of the Dubrovka Theater when they were seen on Russian TV wearing black hijabs and explosive-laden belts.[65] Furthermore, the supposed leader of these women has been referred to as "Black Fatima," a nickname that incorporates racial and religious fears.[66] They are therefore both intimately familiar, yet also monstrously Other, and it is precisely because of their intimacy—because they are, ultimately, like us—that they drive us to the language of exteriority: we say that they are inhuman, and even monstrous, and their acts, evil and unspeakable. We say, in as many ways as we can, they are not like us.

According to Cohen, the monster resides in the "marginal geography of the Exterior, beyond the limits of the Thinkable, a place that is doubly dangerous: simultaneously 'exorbitant' and 'quite close.' "[67] The female Chechen terrorists are strange to many Russians (and even to some Chechens), yet also lie very close to the heart of what Russia is—a state that originated and maintains its hegemonic authority with violence against persons and groups of people who do not possess equivalent force: they are Levinas’s "isolated and heroic being[s],” whom the State produces by its virile virtues"—and therefore, it will never be a matter of simply driving them back to the wilderness from which they supposedly came, nor of just destroying them (Russia's "official policy"). If the only policy against terrorists is to hunt them down and destroy—that is, to kill—them, without conversation, they will keep returning to us, bearing the gift of their deaths and our own murder. If we cannot approach these figures except as monsters, as inhuman, as illegible, then we cannot embark on what Levinas calls the "absolute adventure" of pluralistic being, which is peace itself, but only when we understand that peace "cannot be identified with the end of combats that cease for want of combatants, by the defeat of some and the victory of the others, that is, with cemeteries or future universal empires. Peace must be my peace, in a relation that starts from an I and goes to the other, in desire and goodness, where the I both maintains itself and exists without egoism."[68] But this kind of desiring, which requires that we turn our home (our recollection of ourselves -to -ourselves) into a kind of wandering that allows us to meet and welcome the stranger-Other and even behold her—behold the face of Zulikhan Elikhadzhiyeva—on the plane of the expression of her most enraged and suicidal being, currently exceeds our grasp. It is almost too much to ask. And yet, by her death, she both demands and escapes our attention.

That Terrible and Splendidly Made Spectacle

To Derrida's question regarding how Levinas's ethics of hospitality might be regulated in a juridical practice, or whether or not it could give rise to the law, early English law codes, such as those of Ine, Alfred, and Æthelstan, demonstrate some of the ways in which the figure of the stranger, or lordless man, held a prominent place in the juridical system of Anglo-Saxon England. In the law codes of Alfred (871–899) drafted after the treaty with Guthrum in 886 (referred to as the Danelaw), and modified by Edward the Elder (Alfred's successor, 899–924), it is stipulated that

Gif man gehadodne oððe ælðeodigne þurh enig ðing forræde æt féo oððe æt feore, þonne sceal him cyng beon—oððan eorl ðær on lande—7 bisceop ðere þeode for mæg 7 for mundboran, buton he elles oðerne hæbbe; 7 bete man georne be ðam þe seo dæd sy Criste 7 cyninge, swa hit gebyrige; oððe þa dæde wrece swiðe deope þe cyning sy on ðeode.

[If any attempt is made to deprive in any wise a man in orders, or a stranger, of either his goods or his life, the king—or the earl of the province—and the bishop of the diocese shall act as his kinsmen and protectors, unless he has some other. And such compensation as is due shall be promptly paid to Christ and the king according to the nature of the offence; or the king within whose dominions the deed is done shall avenge it to the uttermost.][69]

In the early English law codes in general (beginning with the seventh-century laws of Ine and extending through the eleventh-century reign of Cnut) the stranger is most often referred to as ælðeodigne [alien person] or feorcumen man [man who comes from afar; foreigner], and occasionally the word gest [guest] is also used, with the term gestliðnesse [literally 'guestliness'] denoting "hospitality." Clearly, the displaced person without specific kinship or local group connections held a special status within Anglo-Saxon England, and Alfred's law, cited above, could even be said to denote a space of legal welcoming of (and hospitality for) the displaced person into the domestic kin-dwelling and protection of the state. In the law codes of Cnut (1020– 23) we can even see the codification of a moral concern for the treatment of strangers, where it states that "he who pronounces a worse judgment on a friendless man or a stranger from a distance than on his own fellows, injures himself."[70]

But in the law codes of Æthelstan (924–939), we can see how the legal welcoming and protection of the stranger also belies a fear of the individual who is too foreign, too displaced, or too unwilling to be attached to the state through a locally circumscribed domicile:

Ond we cwædon be þam hlafordleasan mannum, ðe mon nán ryht ætbegytan ne mæg, þæt mon beode ðære mægþe, ðæt hi hine to folcryhte gehamette 7 him hlaford finden on folcgemote. 7 gif hi hine ðonne begytan nyllen oððe ne mægen to þam andagan, ðonne beo he syþþan flyma, 7 hine lecge for ðeof se þe him tocume.

[And we have declared respecting those lordless men from whom no law may be obtained, that the kin should be commanded to domicile him to common law, and find for him a lord in the district meeting. And if they will not or cannot produce him at the appointed day, then he is afterwards a fugitive outlaw, and let anyone slay him for a thief who can come at him.][71]

Even earlier, in the law codes of Ine (688–725), we can see that the status of the foreigner was ultimately precarious:

Gif feorcund mon oððe fremde butan wege geond wudu gonge 7 ne hrieme ne horn blawe, for ðeof he bið to profianne, oððe to sleanne oððe to áleisanne.

[If a man from afar, or a stranger, travels through a wood off the highway and neither shouts nor blows a horn, he shall be assumed to be a thief, and as such may be either slain or put to ransom.][72]

The line separating the sacred foreigner whose body and possessions should be protected from the person who is available to be killed (by anyone, no less) precisely because he either does not signify his presence or refuses the invitation into the state's dwelling is very tenuous here. One could say that all of the law codes cited above are predicated, in the final analysis, upon the state's desire both to regulate and contain immigrants and disenfranchised persons (as well as eliminate them when they cannot be contained), and also to profit from them through fees of protection and taxation. T he "fate of the foreigner in the Middle Ages—and in many respects also today," as Julia Kristeva has written, "depended on a subtle, sometimes brutal, play between caritas and the political jurisdiction."[73]

Anglo-Saxon law codes point to a legally codified ethics of care for the stranger-Other who is both threatened yet also threatening in his singularity, and they likely arise from a society that we know, from its imaginative and other literature, was deeply concerned with what might be called the protocols of hospitality.[74] And these protocols—in the absence of the law, or beyond the law's reach—functioned as the important means whereby those who were Other to each other could communicate, without hostility, in spaces of common dwelling, whose doors, whether barred or open, marked the threshold between the "inside" of the communal dwelling from the "outside" of the stateless forest. Importantly, the very idea of the extralegal was enclosed within the Anglo-Saxon legal definition of the fugitive as one who was exlex, or utlah [outlaw].

According to Michael Moore, "The forest was the proper haunt for such figures, ranging far from the houses and protection of the village. No food or lodging was to be offered to the utlah." Further, "These criminals, conceived of as demonic creatures outside the boundaries of humanity, were pushed away from the society, absolutely excluded from the shelter of the community and its legal world and suffering what amounted to 'civil death.' "[75] In medieval Ireland and Iceland, "the term 'wolf' was applied to any dangerous foreigner who did not belong to the local community. Wolfishness was also thought to be an attribute of the medieval outlaw, who was deemed to become wolf-like," demonstrating that to exist outside the law, or outside of the known domicile of a particular kin group with specific connections to the state, was to be considered non-human, even monstrous.[76] As Moore writes, "Such acts of exclusion helped to form the community as a legal subject: the law was made by and for the village or kingdom, at the same time enclosing and defining it" and "the concept of outlawry was fundamental to establishing the inner, safe circle of communal law and royal power."[77] The medieval social community, then, had need of an extralegal "outside" in order to define itself as bounded, while, at the same time, because of certain moral imperatives, rooted either in Christian belief or more archaic rituals of hospitality, and also for the purposes of strengthening its numbers (both human and economic), that community also had to leave a door open for the welcome of the stranger-Other.

In the realm of Old English poetry, as Hugh Magennis tells us, a "concern with ideas of community and of the relationship of individuals to communities is widely evident." Further, Old English poetic texts often "raise unsettling questions" about "received notions of community," which are reflected in the antithesis between the corpus’s positive images of "warmth and security," especially of feasting and drinking in secular halls, and the reverse images of "dislocation and alienation," as we get in Seafarer, Wanderer, and The Ruin.[78] The Anglo-Saxon hall—both real and poetic—is an especially conflicted site, as both tribal seat and the civitas (or state) itself, for it is not only the place where a community gathers, happily and in supposed concord, around a meal and drink, but is also "the seat of business, of political brokering and conflicts, where power. . .[is] exercised."[79]

Themes of authority and the betrayal of that authority are, fittingly enough, often played out in the hall, and this is especially so in Beowulf, where the poet describes Heorot at one point as "filled with friends within" who do not, "as yet practice treachery" (1017–19). One could argue that the gestures of welcoming in Beowulf, which are clearly the primary instrument of the ethico-politics of the world of the story—from the coast guard's welcome of Beowulf and his men into Daneland (lines 237–57, 287–300, and 316–19), to Hrothgar's servant's welcome of them into Heorot itself (lines 333–39), to Hrothgar's initial welcome of Beowulf (lines 457–90), to Wealhtheow's bearing of the banquet feast cup to Beowulf after he has killed Grendel (lines 1216–31), to Hygelac's re-welcoming of Beowulf into Geatland (lines 1975–98)—are all fraught with the anxiety and tension that always arises when ideas of sovereignty (whether of the individual, the family/tribe, or the larger polis-state) come up against an ethics of hospitality that is supposed to transcend those sovereignties. So, for example, when Beowulf returns to Hygelac's court after his adventures in Daneland, Hygelac commands his hall to be cleared for the "foot-guests" [feðegestum] (1976) to whom he offers "earnest words" [meaglum wordum] and cups of mead [meoduscencum] (1980), one of which his daughter bears directly to Beowulf (1981–83). Yet Hygelac also reminds Beowulf that he had "mistrusted" his adventure [siðe ne truwode] (1994) all along and had asked Beowulf to "let the South-Danes themselves make war with Grendel" [lete Suð-Dene sylfe geweorðan / guðe wið Grendel] (1996–97). By letting Beowulf know of his not having faith in Beowulf, Hygelac opens up a line of tension within his re welcoming home of the local hero, who clearly understands the challenge (and possible peril) of not properly receiving Hygelac's hospitality, when he concludes his story of his exploits in Hrothgar's country by telling Hygelac,

" . . . ac he me (maðma)s geaf,

sunu Healfdenes on (min)ne sylfes dom;

ða ic ðe, beorncyning, bringan wylle,

estum geywan. Gen is eall æt ðe

lissa gelong; ic lyt hafo

heafodmaga nefne, Hygelac, ðec." (2146–51)[" . . . but he gave treasures to me,

the son of the Half-Danes, according to my own judgment,

that I to you, king of men, wish to bring,

to bestow willingly. On you, still, is all

joy dependent; I have few

near relations, Hygelac [except for] you."]

In other words, Beowulf has to reassure Hygelac, through his hospitable (and loving) language and his gifts, where his loyalties as a warrior (and citizen of Hygelac's Geatland) ultimately lie.

In the case of Wealtheow, as the wife of Hrothgar and hostess of the table of the Danish hall, it is her duty to give to Beowulf, following Grendel's defeat, both wine and gifts, and to wish him good health and prosperity, and she does so, but not without also voicing her concern that Beowulf will always be kind in deeds to her sons [Beo þu suna minum / dædum gedefe] (1226b–27a). Wealhtheow's anxiety over her sons' future may very well be predicated upon her fear that her husband has gone too far in his hospitality and gratitude by having already spoken of Beowulf as a son [sunu] in his mind [ferþe] to whom he would give everything he is able to give (946b–50). Hospitality, then, is not just a form of charity in this world, but is also a type of politics—a politics, moreover, that has its breakable limits, evidenced by the poem's multiple digressions into stories about violence erupting in the very site of reception that makes hospitality possible at all: the hall itself. Therefore, in both the story of Hengest and Finn, told by Hrothgar's scop after Beowulf has defeated Grendel (1071–1159a), and also of the destruction of Heorot itself by the Heathobards, first foretold by the poet (81b–85) and then later retold with great embellishment by Beowulf himself (2032–69a), we hear about the murder of guests in the halls of their former enemies, who have invited them there to share food, drink, and gifts (including women exchanged as brides), ostensibly to smooth over past enmities—which enmities obviously percolate very close to the surface of the structures of hospitality designed to ameliorate them.

It is significant, I think, that Beowulf asks Hrothgar, when first arriving in Daneland to allow him to cleanse, or purify, Heorot [Heorot fælsian] (432b), the great hall of the Danes, which has been the chief object of Grendel's attacks.[80] No hospitality (or politics) is possible while Heorot is polluted with the blood of Hrothgar's subjects, many of whom have also abandoned the hall to sleep (and therefore, to reside) elsewhere (138–43), meaning that not only the hall itself, but also the space of sovereignty it marks, has been deserted. T he Danish community, thanks to Grendel's relentless violence, has no viable or pure center, no gleaming building with which to signify their supposedly generous hearts.[81] But even without Grendel's desecration of Daneland's chief ceremonial and communal space, as the poem makes clear again and again in all of its asides regarding the feuds between Frisians and Danes, Danes and Heathobards, Geats and Swedes, and so forth, it is the men themselves who stain the floors of their halls with each other's blood and also burn the structures of their communities down to the ground. As a result, the poem keeps in perpetual motion what Levinas defined as one of the more distressing tasks of alterity: defining "who is right and who is wrong, who is just and who is unjust."[82]

In his terrifyingly excessive hostility, which the poet describes often as a form of hatred [nið, which can also mean 'envy,' 'terror,' 'evil,' and 'spite,' among a great many other connotations in the corpus],[83] Grendel is the signifier of a politics that transgresses the state, through terror, and thereby transfixes its gaze.[84] Grendel's violence challenges the code of hospitality that founds Hrothgar's great hall (and by extension, the whole jural feud society of Daneland),[85] while it simultaneously expresses a kind of excess of the very same violence that helped build that hall, for Hrothgar's "wide" reputation and the wealth of his court are the chief byproducts of his and his troops' "success in war" and "honor in battle" [heresped and wiges weorðmynd] (64, 65). And because Grendel's seemingly senseless aggression encloses a kind of unconscious insistence on his own murder as the only possible end to that aggression, Grendel refuses conversation with Hrothgar and his Danes, and with Beowulf and his Geats, and thereby forcefully opens a way out of his solitude onto the plane of a certain futurity, which is the plane of his own death, but also of a history beyond the judgment (or sense) of those who would "translate" him into a battle trophy.

In that moment when Beowulf and his Geats return to Hrothgar's court with Grendel's severed head, which they have to drag by its hair across the floor of the great hall [be feaxe on flet boren / Grendles heafod] (1647–48), the "terrible" and "splendidly-made spectacle" [egeslic and wliteseon wrætlic] (1649, 1650) of that head, upon which everyone gazes, is a marvel of alterity that, similar to the face of Zulikhan Elikhadzhiyeva, "gleams like a splendor but does not deliver itself."[86] Seth Lerer has argued that Beowulf's killing of Grendel can be viewed as a "rite of purification" or "sacrificial act" by which Heorot is "cleansed" [gefælsod] (1176), with the return of Grendel's severed head to Heorot serving as the "token" or "sign" [tacne] (1654) of that purification. Further, by delivering Grendel in parts, the monster's body "may remain as parts, safe in their symbolism and inactivity."[87] But I would argue that there is something not completely benign or inert in the spectacle of Grendel's head being dragged across the floor of Heorot, and whether it is tied to the rafter beams or left on its slaughter-pole [wælstenge] (1638), in the words of Jeffrey Cohen, "it smears the formal structure of the symbolic network with its obscene presence—its pleasures, delights, and destructions."[88] Further, as Carolyn Anderson writes, "the banishment of Grendel and his Mother does not rid the world of Heorot or Beowulf of disruptions. The abject (repressed) persistently encroaches on and disrupts the symbolic order, so that the subject is always in process, on trial, and always insecure about the boundaries of identity."[89]

Prior to their violent ends at the hands of Beowulf, Grendel, a "grim ghost" [grimma gæst] (102), and his mother, a "mighty mere-wife" and "sea-wolf" [merewif mihtig and brimwylf] (1519, 1599), live in the landscape that is wild and supposedly unlivable, yet is also situated at the very margin, or border, of the so-called civilized world—specifically, Daneland, whose chief symbol, Heorot, is upheld by the poet as the "best of all houses" [husa selest] (146). Because Daneland's primary symbol, the hall, is architectural—it is a thing made and built by human design and therefore articulates human identity—it stands in stark contrast to the fen paths, dark headlands, and burning mere that mark the monsters' territory (1357–72). One could argue that the hall is not just a metonymy for Daneland (and for its authority), but is, in fact, Daneland itself, for the poet shares no details regarding any village or cultivated fields, or other outlying areas that would surely have attached to such a monumental seat of political and cultural power. There is something peculiar about this glittering and golden world whose light shines over many lands [lixte se leoma ofer landa fela] (311): the only things that really constitute Daneland are the shore that separates it from the rest of the world, the horn-gabled hall, the paved stone road leading to and away from the hall, the blood and flesh-splattered trail that leads to the monsters' mere, and the outland territories of the monsters who are "out there" somewhere,[90] calling to mind, again, Jeffrey Cohen's argument that the monster resides "in that marginal geography of the Exterior, beyond the limits of the Thinkable, a place that is doubly dangerous, simultaneously 'exorbitant' and 'quite close .'"[91] Similar to the world evoked in King Lear, in which there are really only two places—the inside of the houses of degenerate power and the outside with its "all-shaking Thunder" and "House-less heads"—Beowulf's world is partitioned between a sick and ruined civitas and a menacing wilderness.

Grendel is the chief border-crosser between these two worlds— a "fiend from hell" [feond on helle] (101) who has spent twelve winters crafting crimes [fyrene fremman] (101) against Heorot, he is not only Daneland's chief terror, but also its chief terrorist. The descriptions of Grendel within the poem reveal both his inherent unknowability as well as his intimate familiarity, which both fascinates and frightens. He is a "powerful ghost " [ellengæst] (86), a "giant" [eoten] (761), a "dark death-shadow" [deorc deaþscua] (160), a "soul killer" [gastbona] (177), a "secret hatemonger" [deogol dædhata] (275), a "hell-secret" [helrunan] (164), and perhaps most importantly, because it is repeated so often, a "terror," or "one who plays with [or fights] the law" [aglæca] (159, 425, 433, 592, 646, 732, 739, 816, 989, 1000, and 1269).[92] Although Grendel is definitively strange and monstrous, the poet also tells us that he and his mother are descended from Cain (104–14, 1260–68), and therefore they share a human kinship with the other characters in the poem, while also bearing the mark of Cain's pathology.[93] As Ruth Melinkoff reminds us,

Grendel and his mother not only are plainly fleshly creatures but also clearly are more human than beast. Although the poet was sparing with physical descriptions, he provides some vividly revealing details: arms and shoulders (835a, 972a and 1537a), claw-like hands (746–8a and 983b–90), a light shining from Grendel's eyes (726b–7) and his head dragged by the hair (1647–8a). . . .Evil monsters, yes, but with human forms, flesh and minds.[94]

Although Grendel never speaks within the poem, and therefore could be construed by the Geats and Danes as being bereft of a rational or human consciousness, the poet refers often to his mental states. As Katherine O'Brien O'Keeffe has pointed out, when Grendel first approaches Beowulf after bursting into Heorot in the dead of night, "he is angry ('[ge]bolgen," l. 723; 'yrremod,' l. 726), his heart laughs ('mod ahlog,' l. 730), he shows intent ('mynte,' l. 731), and he thinks ('þohte,' l. 739)."[95] More to the point of Grendel's troublingly intimate exteriority,[96] he is simultaneously the "elsewhere ghost" [ellorgæst] (807), "fierce house-guard" [reþe renweardas] (770), and the "hateful hall-thane" [healðegnes hete] (142) whom Hrothgar calls "my invader" [ingenga min] (1776), pointing to his intertwined status with those who lie sleeping in the hall at night, and whom he kills and ingests during his visits there. It would appear that somehow, if even on an unconscious level, Hrothgar recognizes that Grendel is somehow his and the Danes' personal nightmare, and even the poet mentions, at lines 152 and 154–55, that Grendel "had fought for a long time against Hrothgar" and "wanted no peace with any man of the Danish troop." So, while on the one hand the Danes can claim not to know or understand Grendel, part of his ability to terrify them might be partly rooted in Hrothgar’s recognition that somehow and in some way, Grendel’s violence is recognizable as a kind of death-shadow of the very same violence that founded his own hall and might also have a more materially palpable cause that attaches to specific persons or specific places.

That Grendel's feud with Hrothgar's court is personal, and that its original cause might somehow be rooted in Daneland's ostentatious display of its wealth and power in its most visible articulation—the golden keep of Heorot itself—is evidenced in the lines, early in the poem, that Grendel "sorrowfully endured his time in the darkness, [and] suffered distress, when he heard each day the loud rejoicing in the hall, the music of the harp, and the clear song of the poet" [earfoðlice / þrage geþolode, se þe in þystrum bad, / þæt he dogora gewham dream gehyrde / hludne in healle; þær wæs hearpan sweg, / swutol sand scopes] (86–90). One of the reasons Grendel may be particularly angry about this music is the subject matter of the song itself—God's creation of the world (91–98)—for Grendel, as one of the deformed or "harm-shaped" creatures spawned by Cain, likely has a special grievance with God, and also with any men, like Hrothgar and his Danes, who appear to have been blessed by God. One visible sign of this blessing, aside from the Danes' material wealth, is the fact that, as the poet tells us in lines 168–69, because of God, Grendel could not approach or touch Hrothgar's "gift-seat," nor could he "know" God's "mind" or "love."[97] Although the poet does not say so directly, we can assume that Grendel assumes that he is not, never was, and never will be welcome in the hall and the field of un-welcoming that the hall radiates might be part of what undergirds his rage against the Danes who do not (and will not) recognize him as being part of their world such that they could even fathom the idea of welcoming him as a stranger-guest. Perhaps, too, Grendel simply hates all who are foreign to him and recognizes no sovereignty except his own, which sovereignty, moreover, he asserts through the elimination of all others whom he perceives to be in his way. This raises the question, too, of how Levinas’s unconditional hospitality can ever be possible in a world that has need of the idea (and force) of sovereignty.

When Beowulf first arrives in Daneland and is explaining to the coast guard why he is there, as mentioned above, he reveals that he and his men have heard of this "unknown malevolence" [uncuðne nið] (276) that threatens the country of the Scyldings, and he wishes to offer Hrothgar counsel as to how he might vanquish this "I don't know what kind of ravager" [sceaðona ic nat hwylc] (274). It could be argued that it is not fair to say that the Danes have not properly recognized Grendel as belonging, in some fashion, to their world (if even as a type of structural excess), for Grendel stands in stark contrast to more identifiable human enemies— the Frisian or Heathobard who has been invited to dinner and is quietly seething over old grudges, and whose killing sword is always close at hand. These are enemies whose worst motives are understood and even anticipated. Yet it is precisely this more familiar enemy that Beowulf identifies as the ultimate cause of the undoing of Heorot when he returns to Geatland and explains his adventures in Daneland to Hygelac. In other words, it is other men, familiar family members even, and not Grendel, who are Heorot's real threat.

In his speech, lines 2000–162, which constitutes a second telling of his exploits (the first having been already given to us by the poet), Beowulf, either through an amazing prescience or a smart reading of social cues he witnessed while at Hrothgar's court, explains to Hygelac that Heorot will eventually be destroyed by a failed alliance with an old enemy, the Heathobards, through an arranged marriage between Hrothgar's daughter, Freawaru, and Ingeld, the son of Froda, chief of the Heathobards. Indicating to Hygelac that these kinds of alliances rarely hold, Beowulf states, "Often, after the fall of princes, in a short while the deadly spear flies, even if the bride is good" [Oft seldan hwær / æfter leodhryre lytle hwile / bongar bugeð, þeah seo bryd duge] (2029–31). In a strikingly creative moment, Beowulf then imagines the marriage dinner itself, still in the future, when the Heathobards will welcome the Danes into their hall to celebrate the wedding and, for all their good intentions, will eventually be galled by the sight of all the Danes in their glittering ring-mail, which they wrested from the dead bodies of the Heathobards on the battlefield (2032–40). Because the desire for vengeance always wins out over the desire for reconciliation (and even sex), violence naturally erupts, regardless of the protocols of hospitality that have been designed to avoid (or at least dull) such violent impulses.[98]

The poem speaks often of these seemingly ceaseless cycles of tribal violence and their horrific aftermath—the image of Hildeburh, in the Finn and Hengest story, watching as the heads of her son and brother melt as they are being consumed on their funeral pyre, their blood bursting from the gashes in their bodies (1120b–22a), is a signature moment in this respect—but many of the characters do possess some prescience about this cycle, and they even have social codes to contain it somewhat.[99] Some might argue, then, that Grendel is still worse than these familiar enemies because he represents an obdurately opaque type of mythical or archaic violence that will always be worse than anything the men can do to each other.[100] More terrifying still, he cannot be fought with conventional weapons. When Beowulf requests that Hrothgar allow him to fight Grendel, he mentions that he has heard that Grendel, "in his dark thoughtlessness, does not care for weapons" [for his wonhydum wæpna ne recceð] (434), and therefore Beowulf resolves to fight him without sword and shield (437–40). Further, when Beowulf and Grendel are struggling together in hand -to -hand combat in Heorot, and Beowulf's men rush to defend Beowulf with their "ancestral swords" [ealde lafe] (795), the poet tells us that

Hie þæt ne wiston, þa hie gewin drugon,

heardhicgende hildemecgas,

ond on healfa gehwone heawan þohton,

sawle secan: þone synscaðan

ænig ofer eorðan irenna cyst,

guðbilla nan gretan nolde;

ac he sigewæpnum forsworen hæfde,

ecga gehwylcre. (798–805)[They did not know, when they began the fight,

hard-minded warriors,

thinking to swing [their swords] in every direction,

to seek his soul, that [not any of] the best of iron blades,

of any over the earth, nor any war-sword,

could greet that sin-shadow,

for he had forsworn battle weapons,

all sword-edges.]

Additionally, when Beowulf cuts off the head of Grendel's dead body with the ancient giant sword [eald sweord eotenisc] (1558) he finds hanging on the wall of Grendel's mother's cave (and with which he has also killed Grendel's mother), the poet tells us that the blade of the sword burned up and melted due to Grendel's "too hot" blood (1615–17), indicating, once again, the difficulty of penetrating Grendel's body with conventional weapons. Ultimately, Grendel does not answer to standard forms of combat, which we can imagine contributes to his ability to terrorize. In this respect, Grendel appears to be pure, menacing alterity: he does not walk, talk, or fight "straight."

While Hrothgar and his Danes and Beowulf and his Geats view Grendel and his mother as thoroughly Other than themselves, as Carol Braun Pasternack has pointed out, the language in the poem often belies the lines of difference that supposedly separate the men from the monsters, and thereby also reveals what might be called the poem's "political unconscious":

Aglæca characterizes Grendel and the dragon and aglæcwif Grendel's mother, but aglæca also characterizes Sigemund (893a), both Beowulf and the dragon together (2592) and, in two instances, ambiguously either Beowulf or his monstrous opponent, in the first possibly Grendel (739a) and in the second possibly mere-monsters (1512a). Klaeber struggles in his glossary to keep a clear distinction between hero and opponent, identifying the same term as, on the one hand, "wretch, monster, demon, fiend," and on the other, "warrior, hero." But, as George Jack recognizes in his edition, "fierce assailant" indicates the common ground for all the referents.[101]

Further, Pasternack explains that "The aglæcan are also wreccan, and this word and etymologically related terms point even more clearly to an oral-heroic paradigm in which hero and opponent fall within a single concept, the fierce outsider."[102] O'Keeffe has also remarked that the significance of the term rinc [man; warrior] as it is applied to Grendel "is underscored by the number of the times the poet uses the word as a simplex or as part of a compound in the. . .description of Grendel's actions in the hall [when he fights Beowulf]. 'Rinca manige' (l. 728), 'magorinca heap' (l. 730), 'slæpende rinc' (l. 741), and finally of Beowulf himself, 'rinc on ræste' (l. 747), confirm Grendel's connection with the men in the hall."[103]

Perhaps what is most troubling to the Danes is not Grendel's status as either a monster or a man, so much as the seeming unstoppable and unknowable trajectory of his bloody incursions into Heorot. Early on in the poem, the poet notes that Grendel's feud with the Danes was perpetual, that he would never make peace with any Danish man, he would not consent to settle the feud in any manner or by any payment, and he was not regretful about his murders (136, 152–58), all of which give to Grendel the status of an unknown horror who comes, again (geographically, tribally, mentally), from "I know not where." In this sense, it is not possible for Grendel to attain the status of even the man who comes from afar (such as a Beowulf) or alien person, which would, perhaps, make him worthy of some kind of welcoming, for not only his place (or tribe) of origin but also the causes of his hatred are completely unknown to the characters within the poem. But I would argue that this reading of Grendel belies what Hrothgar himself tells Beowulf about who Grendel is and where he comes from. Because it is only the poet who tells us that Grendel and his mother are descended from Cain (and this happens in two definitive instances at lines 102–14 and 1260–68), and therefore it is only the poet who acknowledges Grendel's genealogical link to the human world, it is important, I think, to look closely at how Grendel's chief enemy, Hrothgar, describes and perceives him. A key passage for understanding this—perhaps the key passage—is the somewhat lengthy speech Hrothgar makes to Beowulf (1322–82) after Grendel's mother has burst into Heorot and killed Æschere, Hrothgar's most beloved warrior, rune-counselor, and shoulder-companion (1325–26).

First and foremost, it is clear that Hrothgar understands that the "hand-slayer" [handbanan] (1330) had a comprehensible motivation for her murder: "She revenged that feud when you [Beowulf], last night, killed Grendel" [Heo þa fæðe wræc, / þe þu gystran niht Grendel cwealdest] (1333–34), and further, she "would avenge her kinsman" [wolde hyre mæg wrecan] (1339). At the same time, Hrothgar describes Grendel's mother in somewhat oblique terms as a "wandering slaughter-host" [wælgæst wæfre] (1331) who goes "I know not where" [ic ne wat hwæder] (1331) with her plundered body. But then, in a striking reversal, Hrothgar shares with Beowulf some very specific details (albeit, borrowed from the hearsay of "land-holders among my people," but also from counselors [1345–46]) about who, exactly, Grendel and his mother are, and where they live. In what could even be called slightly excitable tones, Hrothgar explains that some people have seen "two similarly huge borderers, holding the moors, elsewhere ghosts" [swylce twegen / micle mearcstapan moras healdan,/ ellorgæstas] (1347–49), one of whom could "clearly" [gewislicost] (1350) be seen "shaped as a woman" [idese onlicnæs] (1351), and the other, "harm-shaped, tread the exile-path in the form of a man, although he was much bigger than any man" [oðer earmsceapen / on weres wæstmum wræc-lastas træd, / næfne he wæs mara þonne ænig man oðer] (1351–53). Most important, I think, is that Hrothgar knows this ghost has a name, Grendel (1354–55), and that he has no father—given that this is a world in which patrilineal succession is so important, one could argue that Grendel's fatherlessness adds one more layer to his dimension of frightening and unsettling uncanniness, while at the same time, the assumption that he should have a father (and is strangely lacking one) denotes that he is believed to be, like the Danes, a kin-defined person, even a human being. Finally, in this same speech, even though Hrothgar claims that Grendel and his kinswoman "guard a secret land" [Hie dygel lond/ warigeað] (1357–58), he then goes on, in shades of increasing hysteria, to describe in very precise detail this "wolf country": there are fens, windy cliffs, mountain streams under dark bluffs, a flood under the earth, a lake with overhanging branches and frost-covered trees, and at night, strange fires on the water (1357–76).

In Hrothgar's emotional speech to Beowulf, we see that the margins of the world in which the "monsters" live are sublimely secret and treacherous, yet also geographically recognizable (and therefore, navigable). Likewise, the monsters themselves, Grendel and his kinswoman, are both dark shadows, but also corporeally material and even human. It is fairly obvious, I would argue, that Hrothgar is afraid of the secret, yet familiar country in which Grendel and his mother live (otherwise, why hasn't he already launched some kind of counter-offensive there, or traveled there himself to survey the obstacles?), perhaps because he realizes that the difference of this landscape is, as Cohen writes, "arbitrary and potentially free-floating, mutable rather than essential,"[104] just like the bodies of the monsters, or the bodies of the men who sleep within Heorot's high walls. As René Girard has written, "Difference that exists outside the system is terrifying because it reveals the truth of the system, its relativity, its fragility, its mortality."[105] Grendel's and his mother's anthrophagy is very apt in this scenario because it both absorbs the warrior's body "into that big Other seemingly beyond (but actually wholly within, because wholly created by) the symbolic order that it menaces,"[106] and also disperses the warrior's being, like so many pieces of flesh, into the wilderness (a kind of anti-Heorot, the space where no hospitality, no state, and no law is thought to possible). In fact, one of the most terrifying sights for Beowulf and his men when they seek out Grendel's mother in her underwater den is the spectacle of Æschere's head sitting on a cliff beside the burning and blood-swelled waters of the mere (1417–21). Later, when he returns home, Beowulf tells Hygelac how upset the Danes were that they could not properly burn Æschere's body on a funeral pyre (2124–26). The memory of Æschere's body having been both ingested and also discarded, almost as trash, along the tracks of the stateless forest, serves as a frightening rebuke to the idea that anyone could ever be safe, at home, from the enemy.

By leasing Beowulf, as it were, to destroy Grendel and his ilk, Hrothgar is admirably doing everything he can to stop terror from enveloping and decimating his culture, to be sure, although it does raise the difficult question, again, of the difference "between, on the one hand, the force that can be just, or in any case deemed legitimate (not only an instrument in the service of the law but the practice and even the realization, the essence of droit), and on the other hand the violence that one always deems just."[107] Grendel is so terrifying because, for the "hospitable" warrior-polis of Heorot, as Cohen writes, the "maintenance of order. . .is achieved only by the repression of those [murderous] impulses Grendel embodies,"[108] but which nevertheless were once necessary for the building of Heorot, which then becomes the "law" that keeps violence in check through its alliances, man-payments, diplomacy, and when necessary, controlled reprisal. But as Robert Gibbs notes, "the positivity of law depends on a singular [violent] event, a revolution or war," as well as upon the reiteration of that violence through the coercion that preserves the maintenance of the state.[109] And what always puts the law in question (or peril) is the stranger-Other, such as a Grendel, for whom conformity is out of the question and whose violence appears to have no boundaries. Cohen writes that "Grendel represents a cultural Other for whom conformity to societal dictates is an impossibility because those dictates are not comprehensible to him; he is at the same time a monsterized version of what a member of that very society can become when those dictates are rejected, when the authority of leaders or mores disintegrates and the subordination of the individual to hierarchy is lost. Grendel is another version of the wræcca or anhaga, as if the banished speaker of The Wanderer had turned in his exile not to elegaic poetry but to the dismemberment of the cultural body through which he came to be. "[110] Levinas's hospitality, of course, would not be able to succeed within any model of conformity; indeed, it depends on the appearance and welcoming of the non-conformist.

Ultimately, Grendel reserves for himself the privilege of murder that, typically, only the state (Heorot) can authorize, and similar to the suicide bomber who can never be caught or punished because she is already dead (and there will always be another to die again in her place), Grendel holds the place of a primal, sacrificial violence to which the only response is either fear and resignation or the unleashing of a force of the state that operates outside of the usual laws, such as a Beowulf (who is a "special force"). Indeed, it is precisely in Beowulf's "grappling" with Grendel in Heorot (745b–818a), when Heorot literally resounds with Grendel's "wailing cry" [wealle wop] (785) as Beowulf is ripping Grendel's arm and shoulder from his body, that we can glimpse the fluctuating structuration of violence that, tragically, has always undergirded this world.

According to Levinas, "The privileged role of the dwelling does not consist in being the end of human activity but in being its condition, and in this sense its commencement."[111] Without the dwelling, what Levinas calls "recollection"—the "coming to oneself. . .which answers to a hospitality, an expectancy, a human welcome"—is not possible. It is not possible to know, of course, if the underwater mere where Beowulf meets Grendel's mother in combat functioned, in that way, as Grendel's dwelling. But because of what we can imagine to be Grendel's belief that Heorot mocks him and even denies him welcoming access, and because his home—to which he drags himself to die after Beowulf has torn his arm out of its socket—is designated ahead of time by the Danes as everything that is un-homelike, Grendel exists outside the state as the figure of the "extralegal" and is beyond both his own and others' "recollection." Beowulf's murder and post mortem decapitation of Grendel represents what might have been for Grendel a devastating double-dispossession, especially when we consider that Beowulf first drives Grendel out of the "high hall" that is the home of those who are supposedly blessed by a God whose regard Grendel cannot "know," and then later, to add insult to injury, Beowulf desecrates Grendel's body by slicing off his head in the "roofed hall" [hrofsele] (1515) of his mother.[112] And this is a head that, tellingly, will take four men to haul it along the horse-path back to Heorot (1634–39), where, somewhat disturbingly, after being dragged across the floor to where the nobles are sitting on the benches, it becomes a spectacle for silent awe as well as a trophy (1647–50). The building of Heorot was made possible through the spoils of war, and Grendel's severed head is the most visible marker of the monstrous, outsized rage necessary for founding that hall as well as the signifier of the violent coercion necessary for maintaining the law of the hall that, in the final analysis, is not predicated as much upon an ethics of hospitality as it is upon a force of exclusion that makes hospitality for some (as opposed to all) possible.

For the Danes, or even for Beowulf and his men, to even pause to consider how they might substitute for or subject themselves to a Grendel, to face him, as it were, without intermediary (Levinas's face-à-face sans intermediare), would be to contemplate a justice that literally stands beyond the social totality (Heorot itself) that makes thinking possible. It would be to go "where no clarifying—that is, panaromic—thought precedes, in going without knowing where," in order to a grasp a "pluralism" that can never be totalized and without which peace can never be accomplished. It may be, as John Caputo has written of Derrida’s reflections on the possible politics that could be founded by Levinas’s hospitality, that "[u]nconditional hospitality requires a politics without sovereignty," and also a "community without community, a city without walls, a nation without borders. . .where the decision procedure for administration is based on a holy undecidability between insider and outsider." And what would result would be a type of "holy hell" that is "the stuff of sacred anarchy."[113] But how to imagine such an anarchic state of affairs into administrative being? Or, to put the question another way: surrounded by so many bad deaths, both in the poem but also in our own troubled times, how to make way, hopefully, for its shining and chaotic arrival?

Although Grendel can't dine anymore on the beautiful, shining bodies of the Danes, cracking their bones and gulping them down in chunks, nor does the light, which the poet calls "unbeautiful" [unfæger] (727), any more shine through his eyes, his head, suspended in the hall in a moment of Anglo-Saxon time, can keep watching them.[114] He can keep gaping and warning as what Levinas would have called, not a face, but a façade "whose essence is indifference, cold splendor, and silence."[115] L ikewise, Æschere's head, left behind along the cliff beside the burning lake where Grendel's mother discarded it (1421), is also watching and warning. These, finally, are the faces of Beowulf that overflow the boundaries of all images and call into question the nature of the proper relationship of violence to justice, and to the sovereignty of the state. Along with the photograph of Zulikhan Elikhadzhiyeva, these “remains” are the expressions of persons “brutally cast forth and forsaken in the world.”[116] In addition to Heorot itself, once it is destroyed, they are also the "somewheres" of dwellings that can no longer open to themselves, but only to those of us who are willing to behold them, belatedly, with wonder.

ENDNOTES

This essay has been with me, troubling my thoughts and my study, for over three years now, and many have been the readers and friends involved in its evolution. I want to thank, especially, Roy Liuzza, Bruce Gilchrist, and James Earl for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts. I want to also thank Michael Moore, Ann Astell, and Justin Jackson for giving me opportunities to present proto-versions of this chapter at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville's Spring Colloquium, "Thinking about Empire," and at Kalamazoo in 2004.