Eileen A. Joy, Assoc. Professor

Dept. of English Language and Literature

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

ejoy@siue.edu

Monograph-in-Progress:

Improbable Manners of Being: The Queer Lives of Saint Guthlac

BRIEF DESCRIPTION

My book project represents an in-depth study of the eighth- through tenth-century prose and verse legends of the English saint Guthlac of Crowland, [1] whose life comprised vocations as: first, a Mercian warrior chief in East Anglia, then a monk in the monastery at Repton, and finally a hermit saint living in an abandoned grave-mound on the island of Crowland in the East Anglian fens. This study is aimed at two distinct academic audiences: those working in Anglo-Saxon and early medieval studies, where work on the early Guthlac legends has been somewhat sparse and has mainly concentrated on their most immediate linguistic, cultural, and historical contexts, and those working in contemporary queer studies , which has in some significant instances turned to the legends of saints in both late antiquity and the Middle Ages for examples of forms of self-fashioning that are believed to have some affinity with contemporary modes of gay sexuality and identity.

One of the most important works undertaken in sexuality studies is Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality, published in three volumes between 1976 and 1984. Part of Foucault’s project in volume 3, The Care of the Self, was to demonstrate the ways in which a certain aesthetics of sexual pleasure, developed in Greek antiquity, eventually gave way, in Roman moral philosophy and in an emerging scientia sexualis, to a technology of self-regulation in which the sexual became “dangerous.” A fourth volume, never finished, was to take up the ways in which early Christian confessional modes intensified this self-regulation and also helped to produce sexualities as “truths” about selves that could then be disciplined and governed (and even punished). At the same time, in some of the texts of the early Church dealing with monks and saints’ lives and their extreme forms of self-discipline, Foucault saw a way out of this oppressive regime of disciplined sexuality and a way in to what he called “a manner of being that is still improbable”—a manner of being, moreover, that would offer us “an historic occasion to re-open affective and relational virtualities” that he believed could be emancipatory.

Foucault’s thinking on early Christian saints’ lives was raised for me with a certain urgency in relation to some recent scholarship I have been reading on what some scholars view as the “exuberant erotics” of ancient and medieval saints’ lives)—lives, moreover, that portray what one scholar has called the pleasurably “violent seduction of sacrifice.” In Virginia Burrus’s The Sex Lives of Saints: An Erotics of Ancient Hagiography (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), Robert Mills’s Suspended Animation: Pain, Pleasure, and Punishment in Medieval Culture (Reaktion Books, 2005), and Karmen Mackendrick’s Counterpleasures (State University of New York Press, 1999), just to name a few studies, the legends of desert hermits, militant martyrs, and self-mutilating mystics are held up as models of a sexualized asceticism and as radically sublime sites of freedom.

Most important for my own scholarly concerns is a common theme that runs throughout these studies—that the asceticism and self-mutilations dramatized in the lives of early saints and martyrs supposedly open the self to a radical form of “love” that allows us to give ourselves over to the joy of various “divine” pleasures and abandonments. There has also been some recent work in queer theory that valorizes certain forms of Christian and “saintly” abjections, such as David Halperin’s recent proposal in his book What Do Gay Men Want? for an “upbeat and sentimental” abjection that would help us to “capture and make sense of the antisocial, transgressive” behavior of gay men without recourse to the language of pathology or the death drive, and which relies for some of its inspiration on medieval Christianity’s rhetoric of humiliation and martyrdom. Halperin puts forward a model of “queer solidarity” (between gay men) built upon an embrace of one’s own social humiliation and abjection as an “inverted sainthood.”

The question is finally raised, for me, of what kind of “spiritual” work all of these studies are doing with regard to asceticism, saintliness, the sacred, queer relational modes, and love, and whether or not, as a scholar who works in both medieval studies and contemporary queer studies, I think we should be cautious about the supposedly emancipatory relational modes that some scholars have argued are opened within the creative conjunctions between premodern religious practices, asceticism, self-sacrifice, and queer sexuality. I do, in fact, think we should be cautious, and it is my aim in this book-length study of the early English legends of Saint Guthlac to offer an alternative set of readings of a premodern saint’s life that might offer avenues toward new (and queer) relational modes that are founded in positive rather than in negative affects, in pleasure and joy rather than in pain and suffering, and in an affirmation of life rather than an embrace of the death drive. I focus, more specifically, on what I see as affirmative sites of relations that are not necessarily sexual, per se, but which are sensually and affirmatively affective and intimate and which are available in the Guthlac narratives through various readings of his encounters with his demon-torturers, as well as with his sister, Pega (also a hermit), and Beccel, a brother-monk and servant to Guthlac.

Much of the most innovative and important work in queer theory in recent years has been preoccupied with themes of shame, loss, melancholy, suffering, dereliction, anti-sociality, the death drive, and so on,[2] and it is the aim of my book to join a small but growing group of queer theory scholars (including Elizabeth Freeman, Jose Esteban Munoz, and Michael Snediker)[3] who have been developing more affirmative and utopian historiographical methodologies. There is a dearth of monographs within the field of Anglo-Saxon literary studies that are informed by queer sexuality studies or queer historiography,[4] and within contemporary queer studies, there are very few books that attempt to address current theoretical concerns from the longer perspective of premodern studies (and those that do address premodern periods are not always written by scholars specializing in premodern history and culture; therefore, the analysis or use of subject matter from those periods is often historically shallow). It is my hope that my book, when published, would make a significant contribution to an under-represented critical approach in early English literary studies and would also stage an important critical intervention into a field—contemporary queer studies—that rarely explores the complexities of its longer historical dimensions.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- “The Thousand Tiny Itinerants of Guthlac’s Body”: this chapter is an exploration of the themes of fugitive itinerancy, unsettled subjectivity, disenfranchisement, and exile in the early medieval legends of Saint Guthlac, and is intended to demonstrate that the generic role of the hermit saint as isolated outsider is primarily an illusion. The saint can never really be understood apart from the social groups and networks from which he supposedly absents himself or from those persons whom he supposedly displaces in order to make room for his hermitage. The saint is always, ultimately, a multiplicity of inter-subjective beings, never a single being, and he can never really renounce the world, no matter how much he tries.

- “The Swarm Becomes Him”: this chapter is an exploration of the possibility of affective recognition between individuals enmeshed in supposedly impersonal mass institutions and encounters (such as the medieval Church, civil wars, and “demonic” sexual encounters). Through an analysis of what the medievalist scholar Jeffrey Cohen has termed the “dynamic intermezzo” that is formed in Guthlac’s night-flight with a swarm of demon abductor-torturers who carry and drag him through fens and marshes, freezing skies, and down to Hell, I follow and elaborate upon Cohen's argument that, as Guthlac and his demons fly together through Middle Anglian and other space, they form molecular intensities of desire through which they both merge and also maintain their separate identities. Ultimately, the focus in this chapter is on the delineation of certain sites of “felicitous promiscuity” that contain within them the possibility for new affective relations that might help us to glimpse alternative models of queer political alliances built on pleasure rather than on shared pain and loss.

- “The Light of Her Face Was the Voluptuous Index of a Multiplicity of Guthlacs”: this chapter is an exploration of Guthlac’s relationship with his sister, Pega, who briefly lives with Guthlac on Crowland as a fellow-hermit until he banishes her (for reasons that are not entirely clear), and to whom he entrusts his body after his death. Ultimately, the argument of this chapter will be that the queerest love of all that Guthlac cannot allow himself is intimacy with and love of his sister, who serves as a sort of soul-mate to Guthlac. Because medieval hagiography invests in the “delights” of self-denial, sadomasochism, and death, the sister has to be removed from the narrative, with the result that the more life-affirming affects implied in their relationship can be covered over and silenced. These affects remain palpably present, however, in Guthlac’s dying wish to be buried by his sister’s hands and to see the “light” of her face in heaven after death.

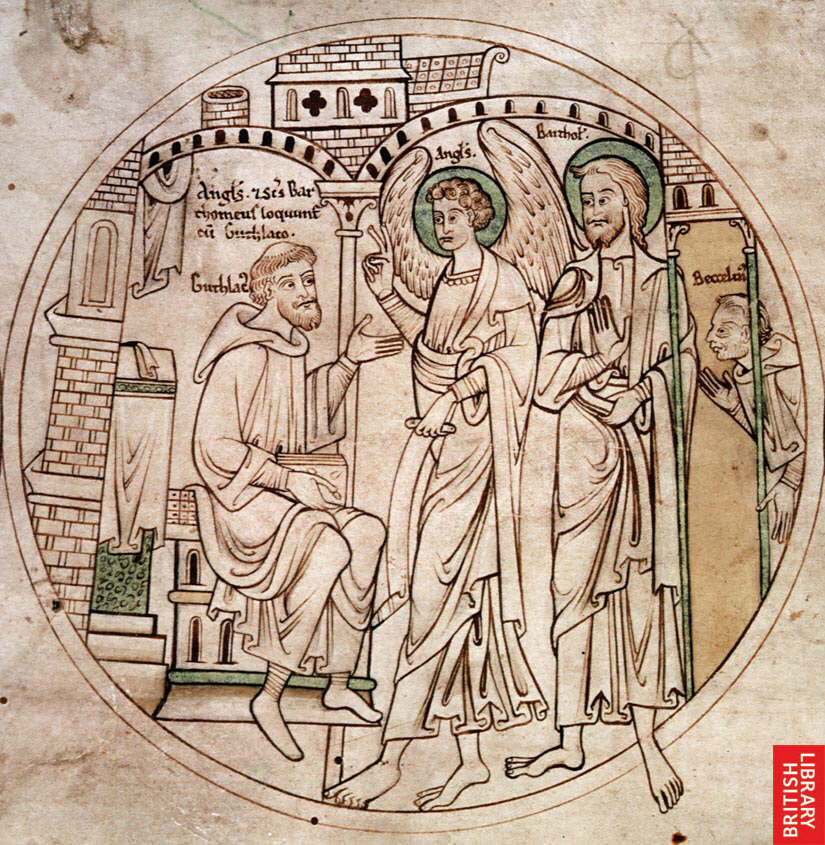

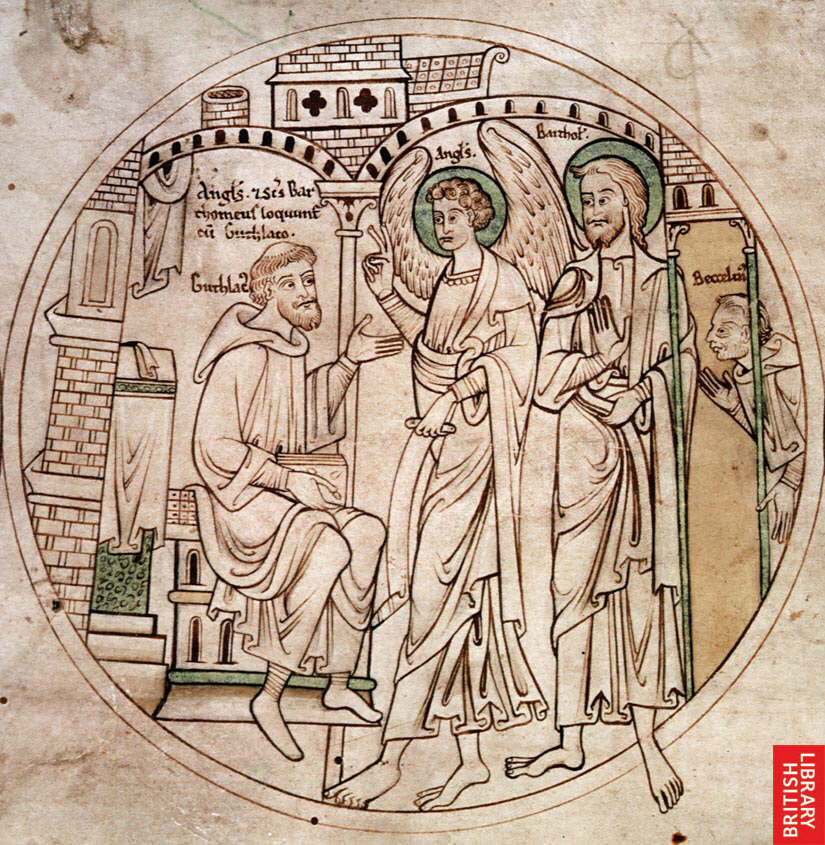

- “The Bedside Mourner and the Politics of Friendship”: this chapter is an exploration of the affirmative possibilities of a queer politics of friendship as enabling important angential intimacies even closer than sexual intimacy, via an analysis of the relationship between Guthlac and Beccel, his fellow monk and serving-brother. This chapter will also propose a politics of queer friendship as a new site for work within the discipline of medieval studies.

* * * * *

ENDNOTES

1. The primary sources for this study are Felix’s 8th-century Anglo-Latin Life of St. Guthlac, ed. and trans. Bertram Colgrave (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1956) and the anonymously-authored 10th-century Old English poems Guthlac A and Guthlac B, located in the Exeter Book manuscript (edition: Jane Roberts, ed., The Guthlac Poems of the Exeter Book, ed. Jane Roberts [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972]).

2. See, especially, Leo Bersani, Homos (Harvard University Press, 1995); Leo Bersani and Adam Phillips, Intimacies (University of Chicago Press, 2008); Judith Butler, Giving an Account of Oneself (Fordham University Press, 2005); Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Duke University Press, 2003); Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Duke University Press, 2004); David L. Eng and David Kazanjian, eds., Loss (University of California Press, 2003); Didier Eribon, Insult and the Making of the Gay Self, trans. Michael Lucey (Duke University Press, 2004); David Halperin, What Do Gay Men Want? An Essay on Sex, Risk, and Subjectivity (University of Michigan Press, 2008); Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Harvard University Press, 2007); Christopher Nealon, Foundlings: Lesbian and Gay Historical Emotion Before Stonewall (Duke University Press, 2001); and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Duke University Press, 2003). This is not an exhaustive list but provides only the tip of the iceberg of work in queer studies that takes up what might be called the negative and anti-sociality theoretical turn. It should also be noted that Sedgwick's work is wide-ranging and takes up somewhat of a missle position with regard to the turn to negative affects in queer theory; her thinking on "reparative reading" and "queer little gods" is especially important in this regard.

3. See Elizabeth Freeman, “Time Binds, or, Erotohistoriography,” Social Text 23.3-4 (Winter 2005): 57-68 and “Turn the Beat Around: Sadomasochism, Temporality, History,” differences: a journal of feminist cultural studies 19.1 (2008): 32-70; Jose Esteban Munoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York University Press, 2009); and Michael Snediker, Queer Optimism: Lyric Personhood and Other Felicitous Persusasions (University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

4. The two single exceptions to this are Allen Frantzen’s Before the Closet: Same-Sex Love from “Beowulf” to “Angels in America” (University of Chicago Press, 2000), which in many respects presents itself as an oppositional text to contemporary queer theory, and also ranges broadly from the early Middle Ages, through the Renaissance, to modern literature, and David Clark, Between Medieval Men: Make Friendship and Desire in Early Medieval Literature (Oxford University Press, 2009).