Book 1 of 8:

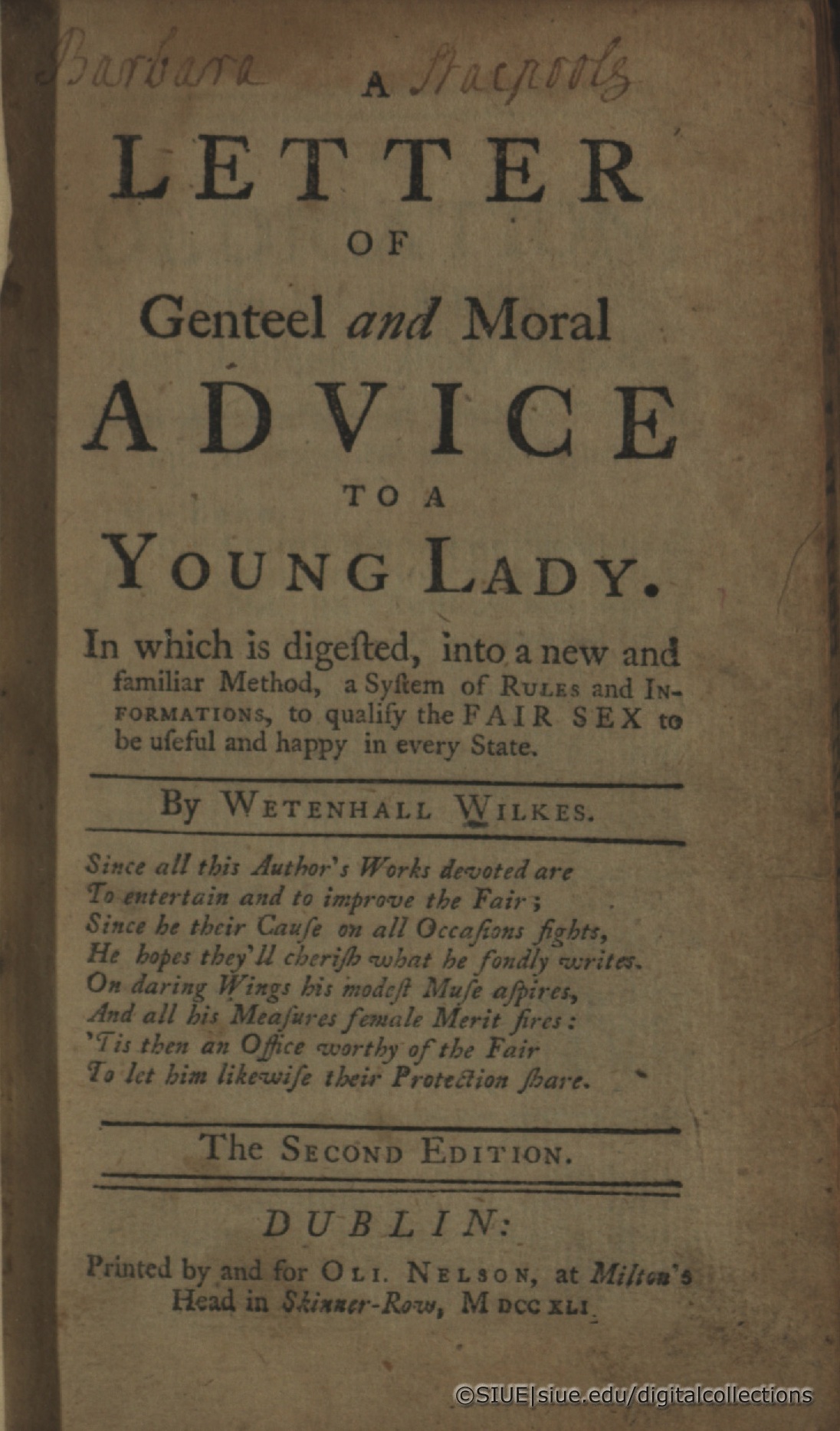

A letter of genteel and moral advice to a young lady: in which is digested, into a new and familiar method, a system of rules and informations, to qualify the fair sex to be useful and happy in every state.

By Wetenhall Wilkes.

The second edition.

Dublin: Printed by and for Oli. Nelson, at Milton's head in Skinner-Row, MDCCXLI [1741].

144 pages, 17 cm (12mo) -- Original edition published in 1740. -- Signatures: [A]4 B-M6 N2 -- Printed on laid paper. -- Brown leather covers. -- Lovejoy Library catalog record.

Wilkes' letter to his sixteen-year-old niece exemplifies the literary genre of the conduct book. It covers topics like comportment, leisure activities, educational pursuits, and preparation for married life.

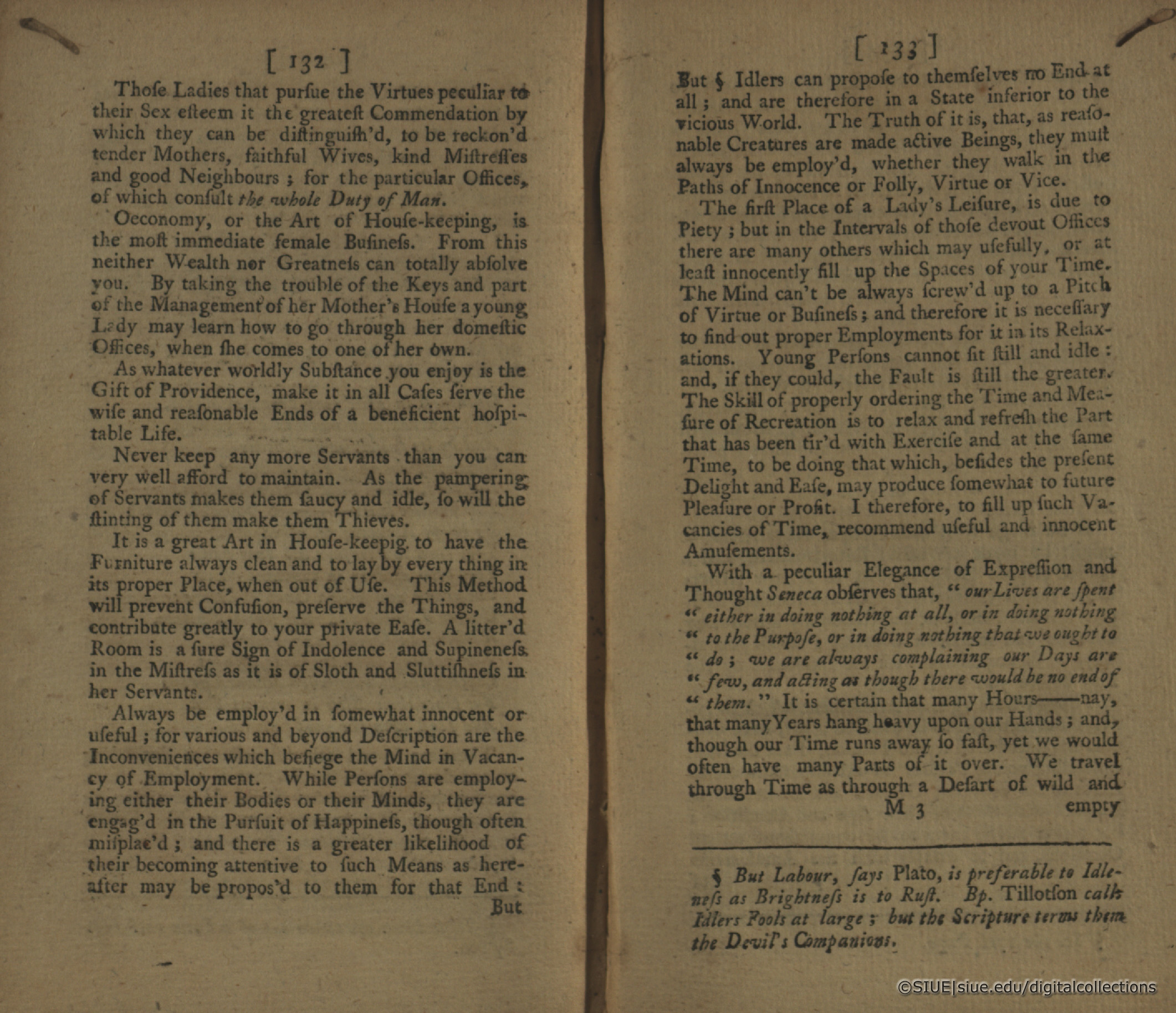

Conduct books addressed young women of the upper and middle classes. Wilkes advises his niece to "[n]ever keep any more servants than you can very well afford to maintain." He gives her tips for keeping a tidy house, noting that "[a] litter'd room is a sure sign of indolence and supineness in the mistress" (p. 132). He acknowledges that his niece's future will likely include a fair amount of grappling with idleness. Needlework features among Wilkes' list of suitable activities to fill her time. In 2005, Christine Hivet asks:

Was not sewing ... the opium of women? Busily employed at their work, they were less likely to resent the society which was shutting them up in the domestic sphere, leaving them both useless and bored. (Hivet 43)

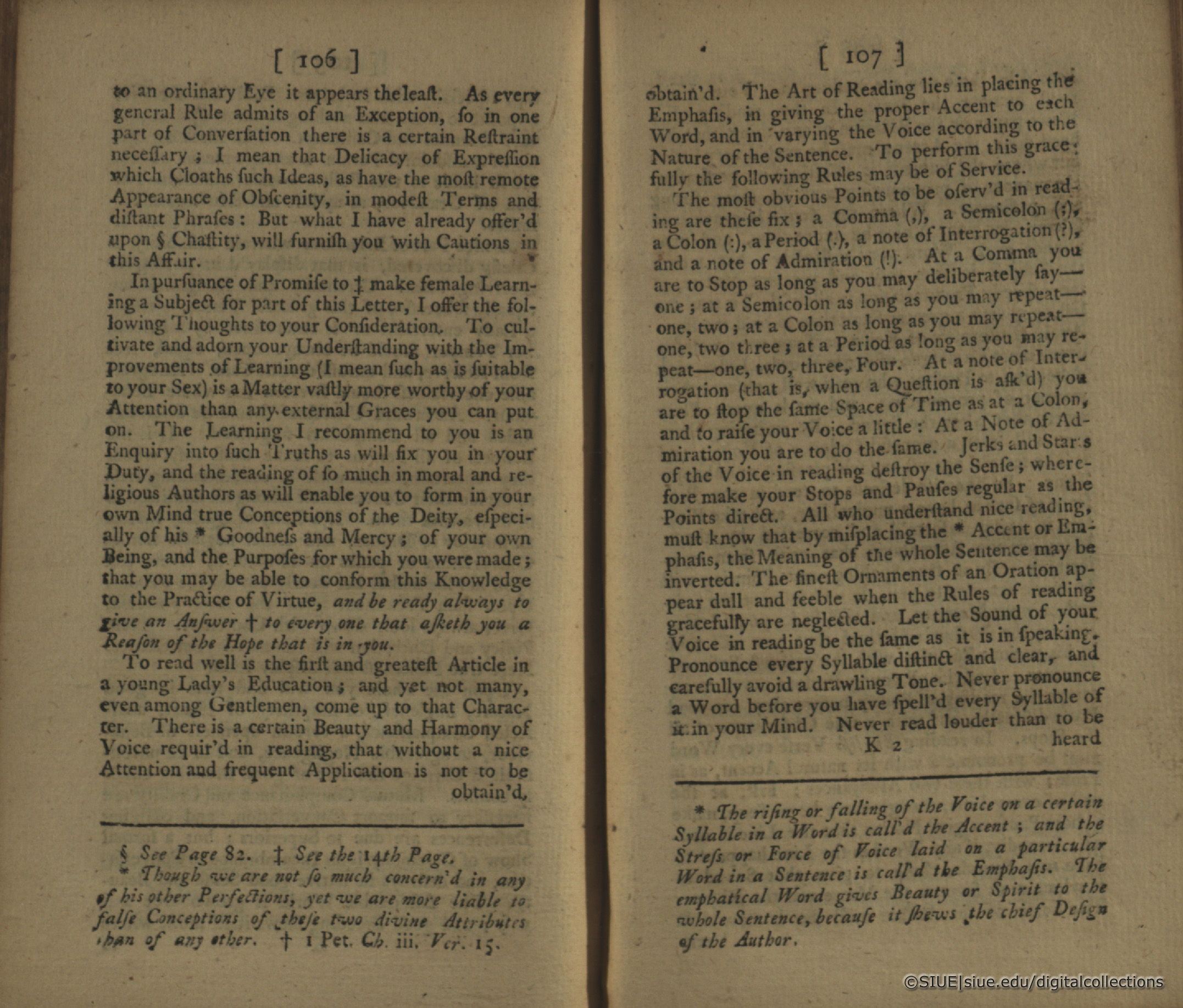

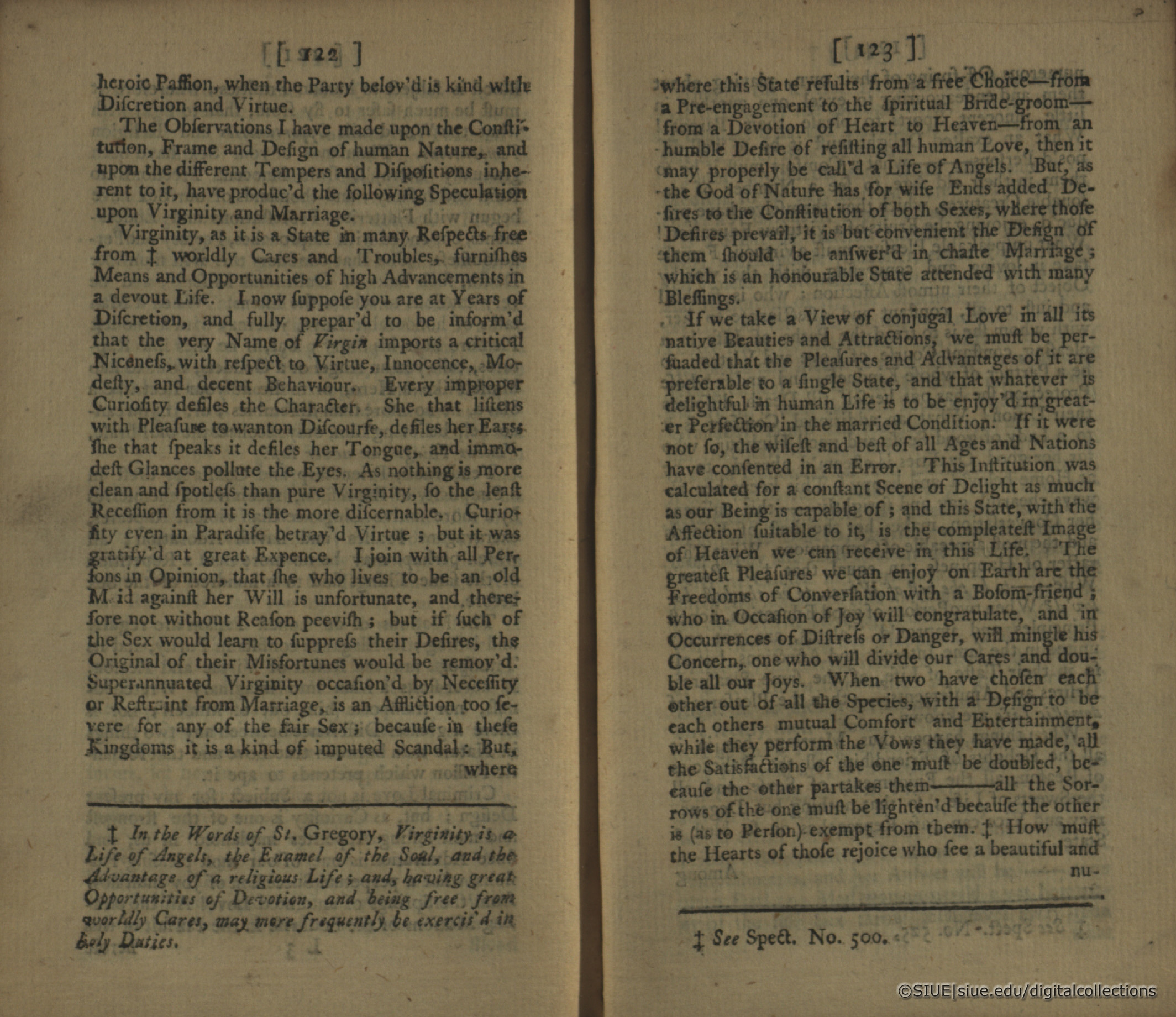

Women in the higher social classes had few career alternatives to that of wife/unpaid head housekeeper. Wilkes observes that being an "old maid" is "unfortunate" and "a kind of imputed scandal" (p. 122). He makes an exception for women who choose perpetual virginity as a form of spiritual devotion. Given these narrow options, Wilkes' limited view of women's education isn't surprising. He states: "To read well is the first and greatest article in a young lady's education" (p. 106). He proceeds with detailed instructions for interpreting different signs of punctuation to achieve the proper emphasis. For example, a lady is to deliberately count silently to herself to one after a comma, three after a colon, four after a period.

British and American women's literacy increased rapidly during the 17th and 18th centuries. The publication of women writers in the late 1700s was a direct result. One wonders if Wilkes, who died in 1751, would have approved.

References:

Hivet, Christine. "Needlework and the Rights of Women in England at the End of the Eighteenth Century." The Invisible Woman: Aspects of Women�s Work in Eighteenth-century Britain. Eds. Isabelle Baudino, Jacques Carré, Cécile Révauger. Hampshire, Eng.: Ashgate, 2005. 37-46.