Aliberti, Vincenzo, Ph.D.

Trans Union (Performance Data Division), Chicago, Illinois,

United States, 60606

Green, Milford, Ph.D.

Department of Geography, The University of Western Ontario,

London, Ontario, Canada N6A 5C2

Abstract

This study examines the spatial distribution of Canada's international merger activity (inward foreign direct investment), for the years 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, and 1991. Log-linear analysis is employed to provide a descriptive examination of the spatial merger flows for the years in question. Internationally, firms based out of the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, acquired the greatest number of Canadian firms. From an acquired perspective, Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia, were the major provincial targets of international merger activity. Foreign firms based out of New York, London (United Kingdom), Chicago, and Los Angeles, acquired the greatest number of Canadian firms. Firms based out of Toronto, Montreal, Calgary, and Vancouver, were the major targets of international merger activity.

Keywords: Canada, foreign direct investment, log-linear

analysis and mergers.

Introduction

This paper addresses one form of corporate growth, expansion through mergers. Specifically, it examines the spatial distribution of Canada's international merger activity (inward foreign direct investment (FDI), for specific years 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, and 1991. To examine the above, three objectives are met. First, given that Canada's economy experienced numerous merger shifts from the mid to late 1940s to the late 1980s, a developmental and historical perspective of Canadian merger activity is presented. Second, a literature review is necessary to properly ascertain the numerous theories that underlie merger behaviour when used as a vehicle for FDI. Last, through the use of log-linear analysis, the spatial distribution (flows) of Canada's international merger activity are determined.

The outline for the remainder of this paper consists of:

1) definitions of mergers, acquisitions, and foreign direct investment;

2) a developmental and historical perspective of Canadian merger activity;

3) a Canadian perspective on foreign direct investment; 4) foreign direct

investment theories; 5) data, methodology, and analysis; 6) international

log-linear analysis; 7) an explanation of the behavior of the firms in

the acquiring centres and firms in the acquired centres; and 8) conclusions.

Defining Mergers, Acquisitions and Foreign Direct Investment

Nelson (1959) states a merger results when two or more independent enterprises combine to form one economic enterprise. An acquisition (or takeover) occurs when an acquiring firm acquires over fifty per cent of the equity of a target firm (Green, 1990). From a business and economic standpoint it is clear that mergers and acquisitions are distinguishable. Spatially, however, mergers and acquisitions are indistinguishable as both represent a process that transfers the corporate locus of control from the acquired firm to the acquiring firm (Dicken, 1976) and possibly from one urban centre to another (Semple and Green, 1983). Therefore, the authors use the term "merger" to represent mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers.

Unlike domestic mergers, international mergers fall under the realm of FDI, with mergers constituting 70% of FDI activity (United Nations, 1995). A popular definition of FDI is that of the United States Department of Commerce that considers investments of 10% or more in a foreign business enterprise FDI. Although there are many definitions of FDI (see Coyne, 1995; and Swimmer and Krause, 1992), for the purpose of this paper, the United States Department of Commerce's definition is used.

A Developmental and Historical Perspective of Canadian merger activity

In this section, three items are addressed: Canadian merger history, United States merger history, and the similarity between Canadian and United States merger waves. In 1969, Grant Reuber and Frank Roseman developed the principal study on Canadian mergers on behalf of the Economic Council of Canada. This study entitled 'The Take-Over of Canadian Firms, 1945-61: An Empirical Analysis', examined all corporations that acquired or were suspected of acquiring other corporations in Canada. The availability and collection of data on mergers became important from post-World War II onwards, since it was from 1945 that conglomerate (two or more firms in related or unrelated industries merge), horizontal (merging firms sell similar product lines in the same geographical market), and vertical (enable corporations to venture into similar or allied product lines enabling the merging corporations to have enhanced sources of 'supply and distribution') merger activity became more pronounced in the Canadian economy.

As Canadian mergers occurred with greater frequencies, distinct merger cycles became apparent. The following table indicates the number of domestic and foreign mergers that have occurred in the Canadian economy from 1945 to 1974.

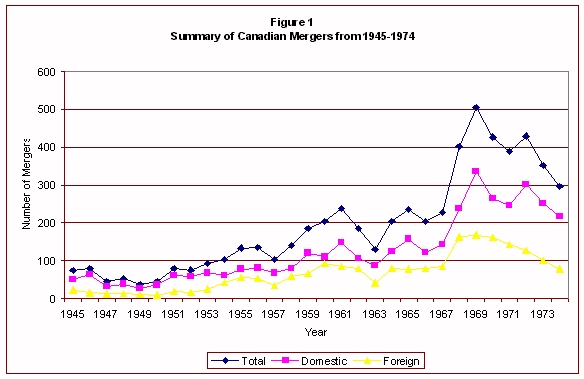

From Table 1, it is evident that there have been distinct merger cycles in the Canadian economy. The years of relatively high merger activity in the Canadian economy were: the last year of World War II and the year that followed, 1945 and 1946; the boom years of 1955 and 1956; the recession years between 1959 and 1961 and; the conglomerate merger years between 1968 and 1972 (Report of the Royal Commission on Corporate Concentration, 1978). Graphically, these distinct merger cycles are illustrated in Figure 1.

Source: adopted from the Report of the Royal Commission

on Corporate Concentration, 1978.

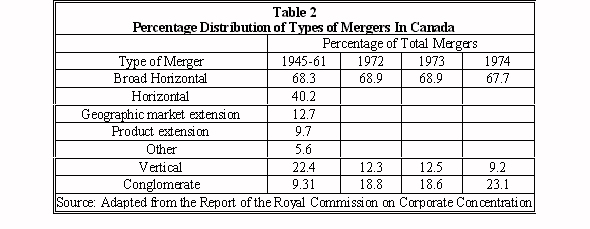

Between 1945 and 1974, not only were there distinct merger cycles, but there were also distinct types of mergers that were employed during this time period (see Table 2).

As shown, the predominant form of Canadian merger activity, both domestic and foreign from 1965 to 1974, was the broad horizontal merger. Approximately 68% of all mergers were classified under the broad horizontal merger category. From 1945 to 1961 these broad horizontal mergers were classified either as straight horizontal, geographic market extension, product extension and other. Over 40% of all broad horizontal mergers were straight horizontal, 12.7% were geographic market extension, while 9.7% and 5.6% were from the product extension and other broad horizontal merger classification, respectively. During the same time frame, vertical and conglomerate mergers combined for 31.7% of Canadian merger activity; of that, 22.4% was represented by vertical mergers, while conglomerate mergers represented the remaining 9.3% of the merger activity. Unfortunately, merger classification statistics for the various merger types from 1962-1971 was not published by the Report of the Royal Commission on Corporate Concentration. From 1972 to 1974, mergers were classified as being either horizontal, vertical and conglomerate. Data on the geographic market extension, product extension and other was not gathered by the Commission. In 1972, 68.9% of all Canadian mergers were horizontal, 12.3% were vertical and 18.8% were conglomerate. In 1973, 68.9% of all Canadian mergers were horizontal, 12.5% were vertical and 18.6% were conglomerate. In 1974, 67.7% of Canadian mergers were horizontal, 9.2% were vertical and 23.1% were conglomerate. It is interesting to note that horizontal and, more importantly, vertical mergers decreased between 1973 and 1974, while conglomerate mergers increased during the same time period. In essence, other than the conglomerate mergers of 1974, the broad horizontal mergers, vertical mergers, and the conglomerate mergers of 1972 and 1973 were relatively similar across the three years of examination. Monopoly power can be more easily obtained through horizontal and vertical mergers, than through a conglomerate merger. One reason for this occurrence can be attributed to the enforcement of the monopoly clauses of the Combines Investigation Act that enabled corporations to consolidate in a conglomerate rather than a horizontal or vertical manner.

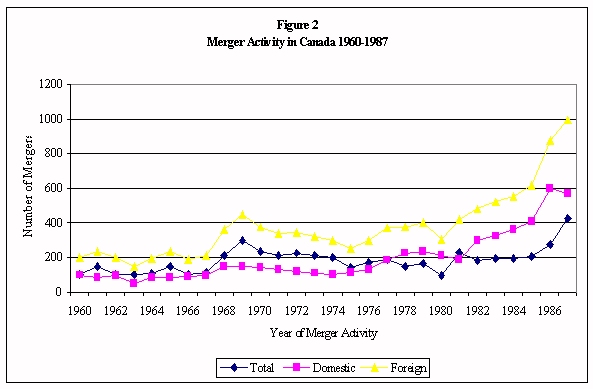

Another historical account of Canadian merger activity is provided in a book titled Mergers, Corporate Concentration and Power in Canada. This book examined Canadian merger activity for the period 1960 to 1987. Figure 2 depicts Canadian merger activity for the period 1960 to 1987 and is an extension of Reuber and Roseman's work done for the Economic Council of Canada.

Source: adopted from Mergers, Corporate Concentration

and Power in Canada, 1988.

It is interesting to note that more foreign than domestic mergers occurred in Canada until 1977, where the same amount of domestic and foreign mergers occurred. From 1978 to 1980 and 1982 to 1987, more foreign mergers occurred than domestic mergers occurred in Canada. Figure 2 confirms Reuber and Roseman's examination of Canadian merger data and, more importantly, illustrates that the Canadian conglomerate wave was not between 1968 to 1972, but rather from 1966 to 1975, peaking in 1969, while the next merger wave began in 1980 and peaked around 1986 or 1987 (Mergers, Corporate Concentration and Power in Canada, 1988). During these merger waves, the Canadian economy was booming. One reason for this Canadian economic boom may be a symptom of the ongoing merger activity.

Since most of Canada's international mergers are with the United States, it is also important to talk about the United States situation. Further, the best historical account of mergers in the western hemisphere, if not the world, is provided from a United States' standpoint.

Four major merger waves have occurred in the history of the United States. The first merger wave began in 1897 and ended in 1904, peaking in 1898 (Nelson, 1959). The industries that experienced the greatest amount of merger activity during this period, according to Nelson's National Bureau of Economic Research study, include; primary metals, food products, petroleum products, chemicals, transportation equipment, fabricated metal products, machinery and bituminous coal. This period is also known for the first billion-dollar merger between United States Steel, owned by J.P. Morgan, and Carnegie Steel, owned by Andrew Carnegie.

Along with this megamerger other great industrial corporations were formed during this merger wave. These include American Tobacco Inc., Dupont Inc., Eastman Kodak, General Electric, Navistar International and Standard Oil (Gaughan, 1996). The first merger wave was characterized by firms attaining monopoly power in their specific industries through horizontal mergers. For instance, United States Steel accounted for 75% of the United States Steel industry's market share, American Tobacco held a 90% market share, while Standard Oil accounted for 80% of its market (Gaughan, 1996). Although the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was in place to prevent anti-competitive behaviour that resulted from monopolistic power of firms, industry consolidation progressed unabated without major antitrust interventions.

There were three major reasons why the first merger wave came to an end. Firstly, the shipbuilding trust collapse in the early 1900s put an end to fraudulent financing. Secondly, the stock market crash of 1904. Third, the Banking Panic of 1907 that closed numerous banks and led to the formation of the Federal Reserve System (Gaughan, 1996). In essence, the first merger wave came to an end because fraudulent financing for mergers was stopped, and the key financial ingredients for takeover activity were halted due to a deteriorated stock market and a feeble banking system.

The second merger wave began in 1916 and ended in 1929. The industries that were impacted by merger activity included primary metals, petroleum products, food products, chemicals, and transportation equipment (Gaughan, 1996). Unlike the first merger wave, which was characterized by monopolistic behaviour and horizontal mergers of firms, the second merger wave was characterized by the oligopolistic behaviour of firms and, by the formation of vertical and conglomerate mergers. In other words, rather than one firm dominating its respective industry, the consolidation of firms gave industry control to a few firms. To monitor the oligopolistic behavior of firms, the Clayton Act was passed in 1914. By using the Sherman Act and Clayton Act, the United States government was better equipped to control anti-competitive behavior of firms. Similar to the first merger wave, numerous prominent firms were formed during this wave including General Motors, International Business Machines, and Union Carbide Corporation. The second merger wave ended on October 24, 1929 (Black Thursday), when the United States stock market crash occurred (Gaughan, 1996).

The third merger wave began in 1965 and ended in 1969. Unlike the first (horizontal) and second (vertical and conglomerate) merger waves, the third merger wave was characterized by the formation of conglomerate mergers. A conglomerate merger occurs when firms in unrelated industries merge. There are three types of conglomerate mergers; product extension, market extension and other types of mergers. According to the Federal Trade Commission, 80% of mergers in the third merger wave were conglomerate mergers (Federal Trade Commission, 1977).

During the conglomerate merger wave, firms continually sought to expand while antitrust regulations from the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950 were employed to strengthen the antimerger regulations that were put in place by the Clayton Act of 1914. In this merger wave, firms used high price earnings ratios (P/E ratio) to justify their growth/expansionary activities. The price earnings ratio is the ratio of the market price of a firm's stock divided by the earnings available to common stockholders on a per share basis. The higher the price earnings ratio, the more investors were willing to pay for the firm's stock, this increased the expectations of a firm's future earnings. It was the high stock values that resulted from the price earnings ratio that helped finance the third merger wave (Gaughan, 1996). When the Tax Reform Act was passed in 1969, it put an end to the playing of the price earnings ratio game and speculative accounting practices by corporations. The Tax Reform Act, along with the ensuing decline of the stock market, ended the conglomerate merger wave.

The fourth merger wave in the United States began in 1981

and ended in 1989. What distinguished the fourth wave from the previous

three waves was the acceptance of hostile mergers (takeovers). In this

period, it was acceptable for a firm to gain corporate growth through a

takeover, since it was a means of obtaining high profits in a short period

of time (Gaughan, 1996). The fourth merger wave can be distinguished from

the previous three waves based on the size and prominence of the merger

targets. The average and median prices of mergers rose from $73.4 and $9.0

million respectively in 1981 to $208.4 million and $32.0 million in 1995

(Mergerstat Review, 1994). The largest merger in this period occurred in

1988 when Kohlberg Kravis acquired RJR Nabisco for $25.1 billion (Wall

Street Journal, 1988). Some of the unique characteristics of the fourth

wave include the:

Aggressive role of investment bankers

in pursuing mergers;

Increased sophistication of takeover

strategies;

Legal and political strategies;

Shareholder activism; and

Amount of foreign takeovers.

The fourth merger wave ended in the late 1980s as the junk market collapsed. This moved the United States into a recession. The recession was short-lived, however, and the megamerger trend began to resurrect itself once again in 1992, predominantly in the following industries drugs, medical supplies and equipment, banking and finance, broadcasting, insurance, and computer software supplies and services (Mergerstat Review, 1994).

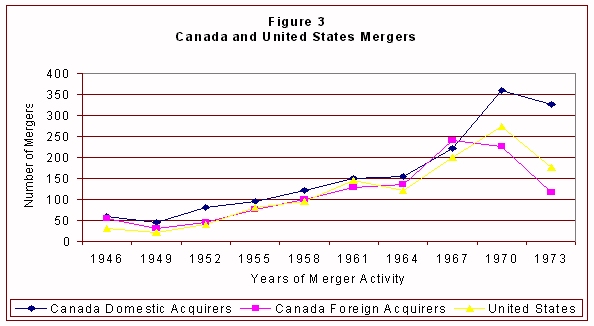

Figure 3 summarizes the Canadian and American merger waves.

Sources: Canada variations in the number

of mergers Canada and the United States, 1945-1974

United States: 1945-1970, U.S. Historical Statistics

(1975); 1971-1974

U.S. Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract

of the U.S. (1976)

Based on Figure 3 one can say that Canadian and United States merger cycles are quite similar. However, there are some differences. The level of Canadian merger activity in the late 1960s, when compared to the base year of 1955, was maintained more in Canada than in the United States, but has decreased relatively less in the early 1970s. Furthermore, in the United States, merger activity has been relatively higher than Canadian merger activity post World War II.

The general similarity between Canadian and Unites States merger cycles is a result of a number of factors. In the Reuber and Roseman study for the period 1945-1961 variations in foreign merger activity in Canada are explained by three factors: the variations of merger activity in the United States; the number of failures in the Canadian commercial sector; and the ability of Canada's economy to stimulate funds in its corporate sector. In other words, foreign merger activity in Canada is influenced by the number of domestic mergers in the United States, and conditioned (influenced) by the level of domestic merger activity and credit conditions of the Canadian economy.

Fluctuations in Canadian domestic merger activity can be attributed to the fluctuations in Canadian stock market prices. Variations in stock market prices reflect the expectations that individuals have about firms when considering a merger; the ability to generate funds in Canada's corporate sector; and the credit conditions within Canada. Based on the results from the Royal Commission on Corporate Concentration (1978) for the time period 1947 to 1974, variations of Canadian and United States merger activity was directly and significantly attributed to the rates of change in stock market prices of the respective country. Given that mergers are the major form of investment in Canada, a review of foreign direct investment theory is in order.

A Canadian Perspective on Foreign Direct Investment

Baldwin and Gorecki (1991) and Globerman (1991) looked

at takeovers of Canadian high-tech firms by foreign firms. They determined

that one of the primary reasons why a foreign firm acquires a Canadian

high-tech firm was its value-added potential following a takeover. McNaughton

(1992) examined the locational and sectoral patterns of United States FDI

coming into Canada for the period 1985 to 1989. He also studied international

investment coming into Canada by examining the behavior of Canadian-based

foreign-controlled firms to that of United States and overseas investors,

for the years 1985 to 1989 (McNaughton, 1992). Meyer (1994) examined the

spatial distribution of outward FDI by Canadian multinational enterprises.

He concluded that the favourite targets for Canada's multinationals were

the United States, followed by the United Kingdom, various countries in

Western Europe, the Caribbean region, Australia, Brazil and various Asian

countries. Aliberti (1998) determined that financial/economic, corporate

infrastructure and trade spatial imperfections (spatial mismatches that

exist between and within nations that stem from differences in economic

and infrastructure conditions) fostered international merger activity coming

into Canada.

Foreign Direct Investment Theories: A Literature Review

It is essential that the determinants that fuel FDI are addressed to better understand the various motivations that are involved in the internationalization process of the firm. Following, is an examination of the FDI theories, beginning with the those based on the principle of comparative advantage.

Comparative Advantage Based Theories

The international trade theory, Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theory, neo-classical location theory and Vernon's product life cycle are the four major theories of comparative advantage. In 1817, Ricardo espoused the most important and most widely recognized concept of international trade theory, the principle of comparative advantage where emphasis is placed on the labour theory of value. This theory states that a country (or geographical area) should specialize in producing and exporting those products in which it has a comparative, or relative cost advantage, compared to other countries and should import those goods in which it has a comparative disadvantage (Ensign, 1995). Ricardo's principle of comparative advantage is subject to a great deal of criticism. Ricardo perceived factor endowments to be geographically immobile between countries but geographically mobile within countries (Rugman, 1980). Land, of course, is the exception. Mobility of factor endowments varies by good. For instance, capital transfers between nations are mobile in nature. In contrast, semiskilled labour is less mobile than skilled labor. Dicken (1992) states that a comparative cost view of the trade theory assumes that transport costs are zero (constant across space) between the trading countries. However, this is not so--transport costs are always incurred when exporting goods between nations. Furthermore, when importing goods from a country, someone has to absorb the transport costs incurred. Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage emphasizes the supply side and the relative abundance of production factors in each country.

A neoclassical approach to the theory of comparative advantage is the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theory (H-O-S theory). Unlike Ricardo's theory, that focused on the labour theory of value and supply side conditions, the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theory emphasizes more than one factor of production (labour and capital), and considers both, demand and supply conditions, through the use of utility curves (Harrington and Warf, 1995). In essence, the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theory demonstrates that a country must possess specific advantages--capital, labour, or resource advantages--in order for economics and trade to exist within and between regions. Models based on comparative advantage help us to explain the association between trade, investment, and government imposed distortions (quotas and tariffs) as they pertain to foreign direct investment.

Similar to Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage, is neo-classical location theory. Neo-classical location theory of foreign direct investment emphasizes supply-side conditions and cost conditions. The major difference between the theory of comparative advantage and neo-classical location theory is that the former emphasizes commercial policy, while the latter focuses on minimization of transportation costs and the availability of raw materials (natural resources), similar to the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson theory, as key variables in determining an optimal production facility. The advantage to neo-classical location theory of foreign direct investment is that a host country's spatially imperfect markets can be exploited by a multinational enterprise (profit maximizer) to establish a production facility. Unlike, classical industrial location theory, which does not consider complex environments and is based on static models, neo-classical location model accounts for the above by adding variability (variable costs) to its models.

Lastly, another theory often used in conjunction with international trade theory to illustrate how foreign direct investment can occur through exporting, at least in the first stage, is Vernon's product life cycle. In 1966, Raymond Vernon developed the three stage product life cycle. In the first stage, the product is unstandardized and produced and sold in the home country. Contact between the firms marketing groups and the product's target market is often maintained (Rugman et al., 1985). Emphasis is placed on research and development activities of scientists and technicians, since the product is being introduced to the market and may have to be modified. During the second stage, the product matures and begins to become standardized. Normally, increases in production and demand are characterized at this stage, these attributes enable the producer to begin "exporting" the product at a less expensive price to foreign nations. The home country's firm still maintains advantages in this foreign nation, since they are the only firm producing the product. However, once foreign firms begin to produce competing products and keep their advantage, the home country's firm internalizes its functions, becomes a multinational enterprise, and begins establishing subsidiaries in the foreign nation's market. In the third stage, the product becomes completely standardized, and since there are firms producing competing products, the firm that sells the product at the lowest unit cost will probably sell more products. In other words, a price-war between the home country's multinational enterprise and host-country firms occurs. Strong cost advantages by the host-country firms normally characterize this stage. If this is the case, it will be in the best interest of the home country's multinational enterprise to stop manufacturing the product and, if anything, simply import the product from the host-country firms (Rugman et al., 1985).

The finance/portfolio theory

The finance/portfolio theory of foreign direct investment espouses that firms seek financial markets in countries where they can diversify their investments to minimize risks. This theory also suggests that firms that invest in foreign nations will obtain a better return on their investment resulting from imperfect financial markets. Other than minimization of risk on their investment, firms can take advantage of favourable fluctuations in interest rates on profit to add to their investment portfolio (Hymer, 1960).

The diversification theory

The diversification theory of foreign direct investment espouses that firms can strategically diversify their operations to expand. Augmon and Lessard (1977) state that before a multinational corporation diversifies, two conditions must be met. First, more barriers must be present for portfolio capital flows than for foreign direct investment. Second, that investors understand that the multinational enterprise is a diversification vehicle for foreign direct investment that would otherwise not be available. By diversifying, a firm can expand into another nation and exploit market structure imperfections such as, monopoly power, that are not easily attainable in the home country. Diversification on a global scale can occur externally, horizontally or vertically, and can result from internal and external forces. If a firm chooses a merger to expand internationally, the conglomerate merger would be best suited to diversify the firm's functions/operations.

Unlike the horizontal or vertical merger, the conglomerate merger can expand into specific product lines, markets, or general operations. Conglomerate mergers have the ability to: share similar marketing channels and production processes through a product extension merger; or enable the merged firms to produce similar products but sell these products in different markets through a market extension merger; or to merge with another firm in unrelated industries to give a clear buyer-seller relationship, or definite advantage over the respective competition. From the diversification theory, we now turn to Kojima's macroeconomic explanation of foreign direct investment.

Kojima's macro-economic approach

Kojima (1978) advocates a macroeconomic approach to make a relationship between trade and foreign direct investment. His macroeconomic approach explains the fostering of trade, rather than devastating trade (oligopolistic or monopolistic behavior). Kojima states that foreign direct investment should take place from the investing nation's relatively disadvantaged industry, that is conceivably a relatively advantaged industry in the host nation. It is primarily a normative theory, as the multinational enterprise is considered a vehicle for the advancement of the comparative trading advantage of countries. According to Kojima, foreign direct investment is viewed both, as a catalyst to trade and an allocator of economic activity. The major flaw with Kogima's macroeconomic approach to foreign direct investment is that he restricts himself to a static interpretation by looking at the trade effects of international investment. He does not consider the dynamic components of foreign direct investment such as employment creation, improvement of the labour force, enhancement of technological capabilities and other externalities (spill-over effects), that may be useful for market penetration (i.e., anti-trade oriented) investments than for trade-oriented investments such as those that include natural resource extraction (Kohlhagen, 1977). Furthermore, Kojima neglects one major tenet of the multinational enterprise, its ability to internalize functions. This is because Kojima is not considering market failure imperfections, since he is working within the neoclassical paradigm of perfect competition. Next, we move to the three transaction cost economics based theories: internalization theory, appropriability theory and the transaction cost theory , or market and hierarchy approaches to foreign direct investment.

Transaction Cost Economics Based Theories

Buckley and Casson (1976), attempted to piece together the various foreign direct investment theories that have been espoused in the past, to construct a more encompassing theory of foreign direct investment, an internalization theory. This transaction cost economics based theory originated from the works of Coase (1937), following previous work on the firm by Knight (1921). Buckley and Casson state that there are two ways in which a firm can 'internalize.' First, a firm can internalize the market by replacing a contractual relationship with unified ownership. Second, a firm can internalize an advantage (production knowledge) to establish a market where no market existed previously (Buckley and Casson, 1985).

In neoclassical economics, markets are assumed to be perfect and firms do not have a clear-cut advantage over other firms, therefore, there is no reason to bypass the market. Presently, the global economic system does not operate under neoclassical economic assumptions and, spatial imperfections in the form of uncertainties in the external market's transaction costs, imperfect markets for knowledge, information, technology and government imposed distortions do exist. Consequently, a firm should weigh its costs and benefits, and if it maintains clear-cut firm specific advantages, then the firm should bypass the market and internalize its functions. The internalization theory recognizes that foreign direct investment is an alternative to exports, licensing, and joint ventures. However, there are costs a firm bears when foreign direct investment is chosen over the alternatives, including, search costs, cultural, and political costs. The internalization theory is a hierarchy approach to foreign direct investment.

Another transaction cost economics based theory that uses the hierarchy approach to foreign direct investment is Magee's appropriability theory. Magee (1976,1977) theory simply combined the industrial organization approach to foreign direct investment with the neoclassical ideas on the appropriability gains of returns on investments that result from sophisticated forms of information. Similar to the internalization theory, the appropriability theory suggests that a firm should internalize specific firm specific advantages (knowledge, information and technology) to bypass the market. Wherever dynamic and innovative product development exists appropriability is vitally important. According to Magee (1976) valuable information is generated by multinationals at five distinct stages: new product discovery, product development, creation of the production function, market creation, and appropriability. A multinational enterprise can use foreign direct investment if it possesses high-end, more sophisticated forms of technology, since this technology is less likely to be imitated, and should expect to receive better returns on their technologies than from simple technologies. Unlike the internalization theory or the appropriability theory that are hierarchy approaches to foreign direct investment, Williamson's transaction cost theory could be either, a market or hierarchy theory of foreign direct investment depending on the circumstances.

Oliver Williamson (1975), transaction cost theory can be used to explain foreign direct investment activity. This theory, originally rooted in organization theory, tries to determine whether a firm's transactions should be governed by the market or hierarchy. He argues that there are three vital dimensions to determine whether a transaction is best governed by the market or hierarchy: the frequency with which a transaction occurs, asset specificity, and uncertainty (Williamson, 1981). As Williamson states, if the frequency of investment increases from a supplier's standpoint, it is better to proceed in two steps: 1) to sway from market contracting to bilateral/obligational market contracting, 2) to sway from bilateral/obligational market contracting to internalization. Of primary importance to a transaction is asset specificity. Unfortunately, Williamson's examination of asset specificity is contrary to empirical evidence, which asserts "that asset specificity encourages market exchanges, while nonspecificity, by endangering property-rights, leads to internalization (Kay, 1992)." In the case of uncertainty, as uncertainty increases, it is better to govern transactions through a hierarchy, rather than through the market. The contrary also holds true.

Dunning's eclectic theory

One of the most celebrated theories of foreign direct investment is Dunning's 'eclectic theory' of international production. Dunning's theory states, that a multinational enterprise will engage in foreign direct investment if three conditions are met. These three conditions are as follows: ownership specific advantages; location specific advantages; and internalization incentive advantages, otherwise known as the O-L-I advantages (Dunning, 1979; 1988; 1990; and 1993). Initially, the firm must possess net ownership advantages in the form of property rights or of common governance that are exclusive to the firm at least, in the short-term. If the corporation possesses these ownership specific advantages, it should internalize its advantages rather than sell or lease them out to other corporations. Assuming that the multinational enterprise has both, ownership and internalization specific advantages in its possession, in order for international production to take place the firm should use these advantages in conjunction with another nation's factor endowments (societal and infrastructure provisions and natural resource endowments). In other words, the multinational enterprise should possess locational advantages of other nations, otherwise domestic sectors of the economy would best be served by domestic production and foreign sectors of the economy would be best served by exports. Since Dunning's eclectic theory is a host nation's perspective of foreign direct investment, a home nation perspective of foreign direct investment is required. Porter's diamond theory of competitive advantage does just that.

Porter's diamond theory

Porter believes that there are four determinants (endogenous variables) that enable a firm to compete on a national level. These endogenous variables are as follows: factor conditions; demand conditions; related and supporting industries; and firm strategy, structure and rivalry. Following, is a description of Porter's endogenous variables.

Factor conditions. The nation's position in factors of production, such as skilled labour or infrastructure, necessary to compete in a given industry.

Demand conditions. The nature of home demand for the industry's product or service.

Related and supporting industries. The presence or absence in the nation of supplier industries and related industries that are internationally competitive.

Firm strategy, structure, and rivalry. The conditions in the nation governing how companies are created, organized, and managed, and the nature of domestic activity (Porter, 1990).

Furthermore, Porter points out that two exogenous variables exist in his diamond theory. These variables are: government and chance. Government policy is definitely an important variable to consider in a firm's national competitive advantage. Government policy can either impede or aid a firm's progress to innovate, or upgrade. Chance events can come in the form of historical accidents, and it is these historical accidents that create a national competitive advantage for a firm (Porter, 1991). Moreover, he states that different dynamics exist between the endogenous and exogenous variables, depending on what stage--factor-driven, investment-driven, innovation-driven, and wealth-driven--of competitive development the nation is in. The first three stages are associated with a continuous improvement of a country's competitive advantages that come with a rising economy. The last stage, wealth-driven stage, deals with stagnation and continuous decline, that is associated with a country's declining economy.

In the case of foreign direct investment, Rugman and Waverman

(1991) citing the Canadian experience, point out one major flaw with Porter's

diamond theory. They believe that Porter has a flawed comprehension of

two-way foreign direct investment. Although Porter examines the exporting

and outward foreign direct investment that takes place by Canada's home

firms, he fails to recognize that importing and inward foreign direct investment

also takes place by Canada's home firms.

Data, Methodology, and Analysis

The international merger data were compiled on a yearly basis in an aggregate form from the Investment Review Division of Industry Canada, for the years 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, and 1991. These data were comprised of the location, city and province, of the acquiring and acquired firms, and the year of the merger transaction. Through initial tests, it was determined that there were only low levels of variation from year to year in merger characteristics. It was more parsimonious to choose representative years that matched census data.

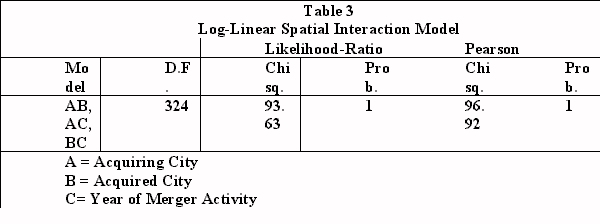

To determine the spatial distribution of corporate control for the aforementioned years, an international spatial interaction model was developed through the use of log-linear analysis. Log-linear spatial interaction modeling is an excellent explanatory and exploratory tool for empirically finding and describing the spatial structure (flows) of the Canadian international merger data. A number of log-linear models are developed, and the model that has the best goodness of fit (model has to meet the 5% significance level) to the data, is chosen.

Through, log-linear analysis one can create a geographic contingency table which one can use to measure the relationships that exist among variables that are measured at discrete levels. In other words, log-linear modeling enables one to postulate multiplicative relationships that exist between the frequency cell counts in a contingency table and the parameter (multiplicative form of log-linear parameter estimates are denoted as beta parameters) estimates of the model. The beta estimates are integrated in relation to the overall geometric mean of one. Values of beta estimates above one indicate increased likelihood of merger occurrence while values less than one indicate decreased likelihood of merger occurrence. The parameter estimates are a measure of the effect or importance of a category in a variable while all other effects are held constant. The parameters of the log-linear model can be statistically interpreted to represent specific interaction effects of the merger data. The contingency table produced from the log-linear analysis provides spatial flows from the data. These flows can be represented in a merger matrix. The matrix comprises the locational attributes of the acquiring and acquired firm, and the year of acquisition of the acquired and acquiring firm. This matrix will allow one to define the spatial flows of international merger activity within Canada (the cities/metropolitan areas that have had the greatest attraction to merger behavior).

Using log-linear analysis, a three way contingency table was developed using the following variables: 1) location of the acquiring firm; 2) location of the acquired firm; and 3) year of merger activity. Once log-linear analysis was employed on Canada's international merger data, the following log-linear spatial interaction model was chosen.

The aforementioned model implies that in order to replicate the spatial effects of Canada's international merger activity, one must ensure that the following are controlled for: 1) the location of the acquiring firm; 2) the location of the acquired firm; 3) the year of merger activity; 4) the spatial interaction effects of the acquiring and acquired cities; 5) the spatial interaction effects of the acquiring cities and the year of merger activity; and 6) the spatial interaction effects of the acquired cities and the year of merger activity. This model is the most parsimonious one that can be derived from the data with a probability level of error less than 0.05.

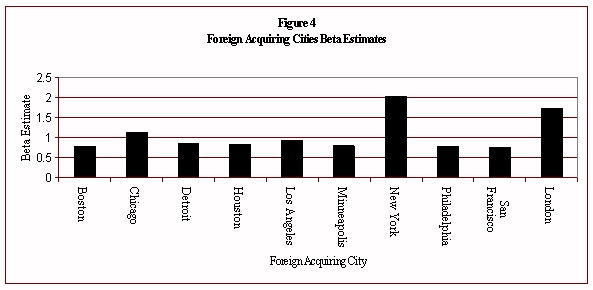

In the case of firms in foreign acquiring cities, it is apparent that two cities, New York (2.03) London (1.74) are an order of magnitude beyond the other foreign cities (see Figure 4). The parameter estimates for New York and London indicate that firms in these cities are 2.03 and 1.74 times more likely to conduct foreign merger activity in Canada, with respect to firms in other foreign cities.

Following New York and London are Chicago (1.12), Los Angeles (0.93), Detroit (0.86), Houston (0.82), Philadelphia (0.79), and San Francisco (0.76). Out of all of these cities only Chicago firms have a parameter estimate greater than one indicating that firms in these cities conduct foreign merger activity in Canada more than firms in the average foreign city. Although the other foreign cities have parameter estimates less than one, they still conduct foreign merger activity in Canada, but at a lesser extent than the average firm in a foreign city.

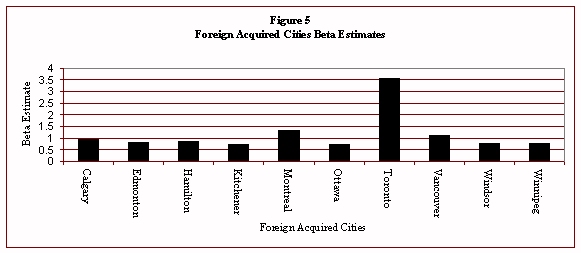

In the case of firms in foreign acquired cities, Toronto (3.56) is the favourite target of firms of foreign cities (see Figure 5). Toronto firms are 3.56 times more likely to have firms in a foreign city acquire firms in it, than in any other Canadian city.

Only two other Canadian cities have beta parameters greater than one; Montreal (1.31) and Vancouver (1.12). In other words, firms based out of Montreal and Vancouver are 1.31 and 1.12 more likely to have firms in foreign cities acquire firms in it, than any other Canadian city, excluding Toronto of course. The firms in the remainder of Canada's acquired cities Calgary (0.92), Hamilton (0.84), Edmonton (0.80), Winnipeg (0.77), Windsor (0.77), Kitchener (0.75), and Ottawa (0.71), all have beta parameters less than one. This indicates that although foreign cities do acquire firms in these cities, the propensity for merger activity is not as great.

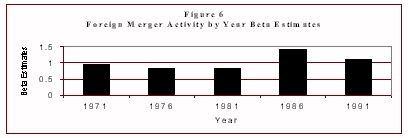

In the case of the year of merger activity, it is apparent that foreign firms conducted more merger activity in Canada in the years 1986 and 1991 (see Figure 6).

The year 1986 with a parameter estimate of 1.43, and the year 1991, with a parameter estimate of 1.10, were the only years where the parameter estimates were above one. This indicates that the propensity of foreign firms to conduct merger activity in Canada was more conducive during these years. Although foreign firms conducted merger activity during in 1971 (0.94), 1976 (0.81), and 1981 (0.83), the activity was not as pronounced, relative to the years 1986 and 1991. The reason why 1986 year's beta parameter was higher than the other years is that Canada experienced a merger wave from the mid to the late 1980s.

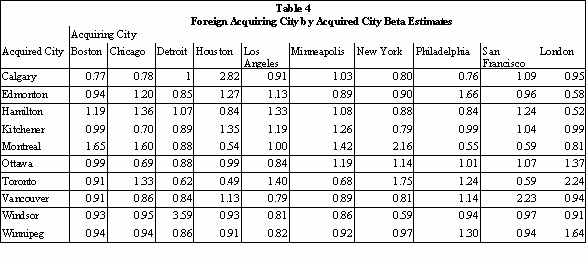

Furthermore, when comparing the merger activity between the firms in foreign acquiring cities and the firms in Canada's acquired cities, some interesting results are apparent. These results can be best examined by looking at the parameter estimates for both, the firms in the acquiring cities and the firms in the acquired cities, in Table 4.

From Table 3, it is evident that firms in foreign cities have favourite merger targets. International merger activity is being fueled by complimentarities in the industrial structures of the respective centres. To prove this, and simultaneously explain the beta parameter results in Table 4, a cross-tabulation was performed on the location and standard industrial classification codes of the acquiring firms and, the location and standard industrial classification of the acquired firms. For the sake of brevity only selected cells of the cross-tabulation are presented here but the entire table is available from the authors.

According to Table 4, New York firms favour Montreal and Toronto firms. Based on the cross-tabulation results of the international merger data, in the case of New York based firms conducting merger activity in Montreal, 21.5% of the activity was in the trade sector of the economy and 14.8% of the mergers were in the services sector of the economy. In the case of New York mergers in Toronto, 20% of Toronto's acquired firms were in trade, 22% were in the services, while 8.1% were in the finance, insurance and real estate (FIRE) sector of the Canadian economy. Firms based out of London (United Kingdom) favoured Toronto and Winnipeg firms as targets. In the case of Toronto, 17.3% of Toronto's acquired firms by London's acquiring firms were in the trade sector, 16.1% were in services and 11.2% were in finance, insurance and real estate sectors. For Winnipeg, 50% of the Winnipeg's acquired firms were either in the trade, or finance, insurance and real estate sectors. Los Angeles based firms had the propensity to acquire Toronto based firms, as 28% of their mergers were in the trade sector, while 23.7% of their mergers were in the services sector. Chicago and Boston firms targeted Montreal firms for merger activity. Respectively, over 22% and 45% of the merger targets of Chicago and Boston based firms, were in the trade sector. Detroit firms favoured Windsor firms for merger activity. This is logical as both cities are automobile manufacturing capitals of their respective nations. Sixty per cent of Detroit based firms acquired Windsor firms that engaged in manufacturing activities. Houston firms favoured Calgary firms as merger targets. This is because both cities extensively focus on the oil industry. Over 59% of Houston's firms merged with Calgary firms in the mining industry. Minneapolis firms favoured Montreal firms for merger activity. Over 33% and 17.5% of Montreal firms acquired by Minneapolis firms were in the services and trade sectors, respectively.

San Francisco firms favoured Vancouver firms for merger activity. Over 28% of San Francisco's firms merged with Vancouver firms in the services sector. Philadelphia based firms favoured Toronto, Vancouver, Edmonton and Winnipeg firms for merger activity. Over 32% and 18% of the Toronto firms that were acquired by Philadelphia firms were in the trade and services industries, respectively. In the case of Vancouver firms, 28.6% of Philadelphia's firms merger targets were situated in the services sector. In the case of Edmonton firms, 66.6% of Philadelphia firms merger targets were either, in the trade or services industries. Over thirty three per cent of Edmonton's acquired firms were in the trade industry and 33.3% of its acquired firms were in the services industry. Whereas, 33.3% of Winnipeg based firms engaged in the service sector were the merger targets of Philadelphia firms. What is striking about the city of Philadelphia is that it is a second tier financial centre in the United States that is also very diversified industrially. This enables it to conduct financial mergers and transactions with two of Canada's financial powers, Toronto and Vancouver, as well as two second tier financial and industrialized cities, Edmonton and Winnipeg.

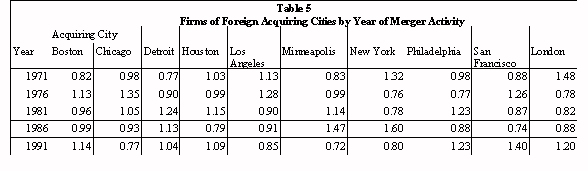

Furthermore, firms of foreign acquiring cities preferred to conduct merger activity in Canada during specific years (see Table 5).

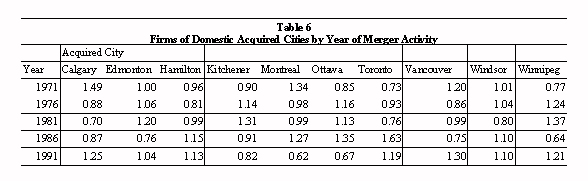

Furthermore, firms of domestic acquired cities preferred to conduct merger activity during specific years (see Table 6).

In the cases of firms of foreign acquiring cities by year

of merger activity and firms of domestic acquired cities by year of merger

activity, it is evident that depending on the year, some acquiring cities

and acquired cities engaged in merger activity with greater or lesser frequency.

This could be because of a number of factors. First, some cities may have

accrued more capital, information and technology in specific industries

that would enable them to engage in international merger activity. Second,

certain industries did well some years, but not so well in other years.

This would explain why certain foreign acquiring centres would acquire

more in those industries during some years, and acquire less in other years.

Third, headquarters locations of numerous corporations in the same industry

may have moved from one city to another city, thereby shifting the locus

of control to another centre. By doing so, capital, information and technology

is lost in one centre, and gained in another centre. Consequently, over

time, merger activity decreases in one centre and increases in the other

centre.

Firms in the Acquiring Centres and Firms in the Acquired Centres: An Explanation

From the aforementioned one can state that firms in certain cities have a greater propensity to acquire firms in certain Canadian cities and, that certain Canadian cities, over others, house firms that are more receptive and conducive to merger activity. From the foreign acquiring city perspective, it is evident that New York and London have the greatest propensity to acquire Canadian firms. New York and London are true global/world cities as both house many global Fortune 500 headquarters, numerous international non-governmental organizations or inter-governmental agencies and, are the main urban centres for their respective nations (Knox and Taylor, 1995). Both cities act as command and control centres of the global economy (Sassen, 1991). In other words, they are global financial centres as they contain many branch, regional headquarters and head offices or representatives of most of the worlds major banks (Thrift, 1989). These two cities act as centres between the multinational/transnational capitalist class and economic elite (Knox and Taylor, 1995). In addition, both have among the best, if not the best, global communication and/or information networks, alongside Tokyo and Paris, that facilitates world scale interaction. By being large metropolitan financial and urban centres that are globally connected from an airline, communication and information perspective, it is no wonder that these centres are the two most prominent acquiring centres of Canadian firms. Following New York and London, are Los Angeles and Chicago. These two centres are intensively populated, maintain a substantial degree of demographic diversity, integrate their local economies with the international world economy, conduct foreign trade, shipping and air freight on an inter presence of international markets and conduct a great deal of transnational investments. However, Los Angeles and Chicago are still considered second tier world cities in comparison to New York. To sum, one can state that New York is the quintessential mercantile city. Chicago is the quintessential industrial city, while Los Angeles is the quintessential post-industrial city (Knox and Taylor, 1995).

Similar to Los Angeles is San Francisco. Neither is the dominant financial centre for the United States, since they are secondary to both New York and Chicago. However, both are important information (Mitchelson and Wheeler, 1994) and financial centres that are located in the same time zone and state (Porteous, 1995). The value/wealth and power of information that is in California has made it possible for these centres to achieve such a prominent metropolitan standing not only in the United States, but the world as well. The reason why California can support two major regional financial centres that are so close in proximity is because its economy is large than both Australia and Canada (Porteous, 1995). Out of the two cities San Francisco houses twelve major United States banks, including Bank of America, in comparison to Los Angeles' ten. According to the 1989 Rand McNally directory of the United States banks, one difference between San Francisco and Los Angeles is that the former houses sixty one foreign banks to Los Angeles' one hundred and twenty five foreign banks. Another difference of course is that San Francisco, with its high tech industries, is more technologically advanced then Los Angeles. By having the aforementioned, as well as being so comparable to Los Angeles, it is no wonder why San Francisco possesses the assets and resources to enable it to conduct an extensive amount of merger activity in Canada.

In the case of the other major foreign acquiring centres, Detroit, Houston, Minneapolis, Boston and Philadelphia, all of them have an advantage that enables them to conduct merger activity in Canada. Other than being major urban areas of the United States, all of them are at the top fifty in the world in terms of revenues in the controlling subsidiary centres by level of centrality (Nahm and Semple, 1995). The level of globalization by a particular centre is measured where it stood in the international quaternary place system, with respect to how much control it exerted over subsidiary centres, in terms of revenue. The higher the centrality score, the higher the degree of globalization. Conversely, the lower the centrality score, the lower the degree of globalization. These centres have been able to accumulate and organize capital internationally by employing mergers as a vehicle for foreign direct investment. Detroit, for instance, is the automobile capital of the United States. Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors are headquartered in Detroit. Houston is renowned for its interests in the oil industry, in the same way that Calgary, its Canadian counterpart is engaged in the oil industry. Boston, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis are cities with a good reservoir of financial resources as well as, being among the top fifteen centres in the United States for generating information--command and control functions and specialized producer services--(Mitchelson and Wheeler, 1994). This enables these cities to conduct foreign direct investment through merger activity.

In the case of foreign acquired cities, it is no surprise that the top four Canadian metropolitan centres Toronto, Montreal, Calgary, and Vancouver, have the greatest propensity to attract foreign merger activity. Toronto of course, is by far the city that has the most firms acquired by foreign firms, followed by Montreal, Calgary, and Vancouver, respectively. These four cities simply possess, the greatest amount of capital, information and technology. Furthermore, they integrate their local economies with the international world economy, exercise control through corporate headquarters, and are connected globally with their communication and airline networks (Toronto and Montreal more so than Vancouver and Calgary), with respect to other Canadian cities. Calgary is a special case, however. Although it is one of Canada's major financial centres, it is different than the other three cities. Calgary is renowned for one resource, oil. It is this resource that stimulates its primary industry, the oil industry. This industry enables it to have a comparative advantage over other Canadian cities and thus, attract industry specific foreign merger activity. The remaining six Canadian acquired centres, although they possess some of the attributes of Canada's top four centres, they possess these characteristics, but at a smaller scale. Therefore, they provide a conducive environment for foreign merger activity, but they do not have as much to offer, when compared to Canada's top four centres.

What is particularly striking is that all of the major

foreign acquiring cities come from countries that share a common legal

and linguistic background, the United Kingdom and the United States. In

other words, since these nations are culturally similar, it makes sense

that the greatest amount of foreign merger activity into Canada comes from

the cities of these nations. Along with foreign merger activity coming

into Canada being a culturally rooted phenomenon, the friction of distance

could also be a factor for foreign direct investment behavior. In the case

of the United States, the distance between the major acquiring United States

centres and the major Canadian acquired centres is small, when compared

to other foreign cities. Since the friction of distance is not as great,

firms from the United States are more inclined to conduct foreign merger

activity in Canada. In essence, foreign merger activity can be considered

both a cultural and distance based phenomenon (Dunning, 1993).

Conclusions

Merger activity coming into Canada (inward FDI) has been cyclical in nature. And, as mentioned previously in this paper, the majority of the merger cycles have occurred post World War II. During these merger cycles Canada's inward FDI via mergers has been encouraged as well as, discouraged. Some of the reasons why inward FDI via merger activity can be encouraged are: the legal and political strategies that are in place, shareholder activism, increased sophistication of takeover strategies, and the economic/financial structure of the Canadian market. The converse also holds true! For instance, from a legal and political strategies standpoint, merger activity coming into Canada can be easily discouraged by a passing of a single legislative act. The Combines Investigation Act is a testament to this. This act hindered horizontal and vertical consolidations in order to extirpate the monopolistic nature of the Canadian merger market. Furthermore, there are certain conditions that enable international firms to invest abroad into Canada such as favorable exchange rates, taxation issues, or the potential to increase global market share.

Two progressive and prominent theories provide a great deal of insight and rationale into what I have said in the above paragraph, Porter's Diamond Theory (domestic focus) and Dunning's Eclectic Paradigm (International focus). From a domestic standpoint, inward FDI via mergers will be induced when Porter's endogenous (factor conditions, demand conditions, related and supporting industries, and firm strategy, structure and rivalry) and exogenous (government and chance) variables are maximized within and between firms to ensure a stable investment environment in Canada. From an international standpoint, Dunning's suggests that the O-L-I conditions are required for firms to consider investing abroad. In other words, international firms must possess ownership specific advantages, location specific advantages, and internalization incentive advantages in order to conduct outward FDI via mergers into Canada. From a historical and theoretical standpoint there are a myriad of reasons for why a host country, in this case Canada, has firms that are solid merger targets and, there are just as many reasons, for why home country firms or international firms, have abundant resources and market structure within their country to logically take the next step to conduct outward FDI via mergers into Canada.

This paper places the aforementioned in perspective by examining the spatial distribution of Canada's international merger arena for specific years, 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, and 1991. To recapitulate, firms based out of the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany, acquired the greatest number of Canadian firms. From an acquired perspective, Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec, were the provinces that were the major targets of international merger activity. Foreign firms based out of New York, London, Chicago, and Los Angeles acquired the greatest number of Canadian firms. Firms based out of Toronto, Montreal, Calgary, and Vancouver were the major targets of international merger activity.

Over time, this international merger activity in Canada has created regional implications as some centres have become more pronounced and conducive to such activity over others notably, Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, and Calgary. If this trend continues, a disproportionate economic shift will be transferred to the aforementioned four centres. This economic shift will be accompanied by agglomeration economies and further produce regional inequalities between centres.

In essence, the case of Canada is somewhat unique. Its'

long history of economic interdependence with the United States has made

two bodies of theory particularly relevant. Merger theories are of obvious

relevance but Canada's reliance on external investment capital makes foreign

direct investment theories equally important! Although Porter's Diamond

Theory and Dunning's Eclectic Theory advance the FDI and mergers theoretical

framework considerably, since individual mergers tend to exhibit some idiosyncratic

traits, one has to understand that one theory will not fit all. We as yet

do not have a unified theory of mergers or of FDI. As the analysis shows

in the geographic patterns of Canadian international mergers activity,

each significant locational pair has case specific reasons drawn from the

literature. So, although some generalizations can be made regarding overall

activity, there is still a need for an appeal to a wide range of theoretical

models.

References

Aliberti, V. 1998. Canada's domestic and international

mergers and acquisitions: a spatial imperfections

dimension. Ph.D. dissertation,

The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.

Augmon, T.B., and Lessard, D.R. 1977. Investor recognition

of corporate international diversification.

Journal of Finance September:

1049-1055.

Baldwin, J. R. and Gorecki, P.K. 1991. Distinguishing

characteristics of foreign high technology

acquisitions in Canada's manufacturing

sector. Statistics Canada.

Buckley, P.J. and Casson, M. 1985. The economic theory

of the multinational enterprise. London: The

Macmillan Press Ltd.

Buckley, P.J. and Casson, M. 1976. The future of the multinational enterprise. London: Macmillan Press.

Coase, R.H. 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica 4: 386-405. Combines Investigation Report (1976).

Combines Investigation Report (1976). Ottawa.

Corporate Taxation Statistics (1974). Ottawa.

Coyne, E.J. 1995. Targeting the foreign direct investor:

strategic motivation, investment size, and

developing country investment-attraction

packages. Boston : Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dicken, P. 1992. Global shift: The internationalization

of economic activity (2nd ed.). New York: The

Guilford Press.

Dicken, P. 1976. The Multiplant Business enterprise and

geographical space: some issues in the study of

external control and regional development.

Regional

Studies 10: 401-412.

Dunning, J.H. 1993. The Globalization of business: the challenge of the 1990s. New York: Routledge.

Dunning, J.H. 1990. Dunning on porter: reshaping the diamond

of competitive advantage. Paper prepared

for the Academy of International

Business.

Dunning, J.H. 1988. The Eclectic paradigm of international

production: a restatement and some possible

extensions. Journal of International

Business Studies Spring: 1-31.

Dunning, J.H. 1979. Explaining changing patterns of international

production: in defence of the eclectic

theory. Oxford Bulletin of Economics

and Statistics

41: 269-95.

Ensign, P.C. 1995. An examination of foreign direct investment

theories and the multinational firm: a

business/economics perspective. In

The location of foreign direct investment: geographic and

business approaches, ed. M.B.

Green, and R. B. McNaughton, 15-27. England: Avebury Ashgate

Publishing Ltd.

Federal Trade Commission. (1977). United States.

Gaughan, Patrick. 1996. Mergers, Acquisitions and Corporate

Restructuring. New York: John Wiley &

Sons, Inc.

Globerman, S. 1991. Continental accord : North American

economic integration Vancouver : Fraser

Institute.

Green, M.B. 1990. Mergers and acquisitions: geographical

and spatial perspectives. London and New

York: Routledge Publishing.

Harrington, J. W. and Warf, B. 1995. Industrial location

: principles, practice, and policy. London:

Routledge.

Hymer, S. 1960. The International Operations of National

Firms: A Study of Direct Investment. Ph.D.

dissertation, Massachusetts Institute

of Technology.

Kay, N.M. 1992. Markets, false hierarchies and the evolution

of the modern corporation. Journal of

Economic Behaviour and Organization

17: 315-333.

Knight, F.H. 1921. In Risk, Uncertainty and profit,

ed. G.J. Stigler (1971). Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Knox, P. and Taylor, P. (1995). World cities in a world-system.

Cambridge; New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Kohlhagen, S. 1977. Exchange rate changes, profitability,

and direct foreign investment. Southern

Economic Journal 44: 43-52.

Kojima, K. 1978. Direct foreign investment: a Japanese

model of multinational business operations.

London, England: Croom Helm.

Magee, S.P. 1977. Information and the multinational corporation:

an appropriability theory of direct foreign

investment. In The new international

economic order: the north-south debate, ed. Bhagwati, J.N.

Cambridge, Massachussets: MIT Press.

Magee, S.P. 1976. Technology and the appropriability theory

of the multinational corporation. In The new

international economic order: the

north-south debate, ed. Bhagwati, J.N. Cambridge,

Massachussets: MIT Press.

McNaughton, Rod. 1992. U.S. Foreign direct investment

in Canada, 1985-1989. The Canadian Geographer

36 (2): 181-189.

McNaughton, Rod. 1992. Patterns of foreign direct investment

in Canada 1985-1989. Canadian based

foreign, controlled firms versus U.S.

and Overseas Investors

Geographica 36 (1): 50-56.

Mergerstat Review. New York. Merrill Lynch Business Brokerage and Valuation, 1994, p. 61

Mergerstat Review. New York. Merrill Lynch Business Brokerage and Valuation, 1994, p. 7.

Mergers, Corporate Concentration and Power. 1988. Ottawa.

Meyer, S.P. 1994. Canada's multinationals: a study

in outward foreign direct investment. Ph.D.

Dissertation, Department of Geography,

The University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

Mitchelson, R. and Wheeler, J. 1994. The flow of information

in a global economy: the role of the

American urban system in 1990 Annals

of Association of American Geographers 84 (1): 87-107.

Nahm, K.B. and Semple, R.K. 1995. Concentration and dispersion

of global control links and changes in

The multinational quaternary place

system. In The location of foreign direct investment:

geographic and business approaches,

ed. M.B. Green and R.B. McNaughton, England: Avebury

Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Nelson, R.L. 1959. Merger movements in American industry

1895-1956. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

Porteous, D.J. 1995. The geography of finance: spatial

dimensions of intermediary behaviour. Avebury:

Brookfield.

Porter, M.E. 1991. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strategic Management Journal 12: 95-117.

Porter, M.E. 1990. The competitive advantage of nations. New York: The Free Press.

Report of The Royal Commission on Corporate Concentration. 1978. Ottawa.

Reuber, G.L. and Roseman, F. 1969. The Takeover of

Canadian Firms, 1945-1961: An Empirical Analysis.

Ottawa.

Robertson, D. 1971. The multinational enterprise: trade

flows and trade policy. In The multinational

enterprise, 169-203. Middlesex,

ed. J.H. Dunning, England: Penguin Books Ltd.

Rugman, A.M. 1980. Multinationals in Canada: theory,

performance, and economic impact. Boston:

Martinus Nijhoff Publishing.

Rugman, A.M., Lecraw, D.J., and Booth, L.D. 1985. International

business: firm and environment. New

York: McGraw-Hill.

Sassen, S. 1991. The global city : New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Semple, R.K. and Green, M.B. 1983. Interurban corporate

headquarters relocation in Canada. Cahiers de

Geographie de Quebec 27: 389-446.

Swimmer, D. and Krause, W. 1992. Foreign investment

in Canada: measurement and definitions.

Investment Canada, Working Paper,

No. 12.

Thrift, N. 1989. New models in geography: the political-economy

perspective. London : Winchester,

Massachussets : Unwin-Hyman.

United Nations. 1995. World investment report 1994:

transnational corporations employment and the

workplace. New York: United

Nations.

United States Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States. 1976.

United States Historical Statistics. 1975.

Vernon, R. 1966. International investment and international

trade in the product cycle. Quarterly Journal of

Economics May 80: 190-207.

Williamson, Oliver E. 1981. The economics of organization:

the transaction cost approach. American

Journal of Sociology 87 (3):

548-577.

Williamson, Oliver E. 1975. Markets and hierarchies:

analysis and antitrust implications. New York: Free

Press.