The Signs and Location of a Flight (or Return?) of Time: The Old English Wonders of the East and the Gujarat Massacre

Eileen A. Joy

**this is a copy of a chapter that appears in Cultural Diversity in the British Middle Ages: Archipelago, Island, England, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, Aug. 2008)

Abstract: examines two widely divergent instances of sexualized violence against women whose bodies have been figured as foreign and barbaric threats within collective national bodies: the real case of a massacre in the modern state of Gujarat in southwestern India in 2002 and the imaginative case of Alexander the Great’s massacre of a race of giant women in the fantasized Babilonia of the Anglo-Saxon Wonders of the East.

For all colonization involves the taming of the beast by bestial methods and

hence both the conversion and projection of the animal and human, difference

and identity. On display, the freak represents the naming of the frontier and

the assurance that the wilderness, the outside, is now territory.

—Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic,

the Souvenir, the Collection

The historian never knows which.

In his account of the possession of the Ursuline nuns of Loudon, France in the 1630s, Michel de Certeau concluded that this possession ultimately “has no ‘true’ historical explanation, since it is never possible to know who is ‘possessed’ and by whom.”1 However, as an historical and even socio-psychological crisis—for those nuns who believed themselves to be possessed as well as for their witnesses, intercessors, and judges—the possession revealed “an underground existence, an inner resistance that has never been broken.” To the question of whether this possession was “something new, or the repetition of the past,” Certeau answered:

The historian never knows which. For mythologies reappear, providing the eruption of strangeness with forms of expression prepared in advance, as it were, for that sudden inundation. These languages of social anxiety seem to reject both the limits of a present and the real conditions of its future. Like scars that mark for a new illness the spot of an earlier one, they designate in advance the signs and location of a flight (or return?) of time.2

In this essay, I want to examine two widely divergent instances of what I understand to be a compulsive and sexualized violence against women whose bodies have been figured as foreign (and even, as animal and barbaric) threats within collective national bodies: the real case of a massacre in the modern state of Gujarat in southwestern India in 2002 and the imaginative case of Alexander the Great’s massacre of a race of giant women in the fantasized Babilonia of the Anglo-Saxon Wonders of the East. Both cases reveal, I believe, certain persistent social anxieties about the female body as, in Elizabeth Grosz’s terms, “a formlessness that engulfs all form, a disorder that threatens all order,” and a “contagion.”3 Out of the horror and disgust that sometimes arises in the encounter with the female body that is perceived as aggressively monstrous, and which is seen to mark, in the words of William Ian Miller, “a recognition of danger to our purity,”4 we can trace a very ancient and ritualized type of reactionary (riotous, yet also highly controlled) violence that is both morally condemnatory and sublimely (even sexually) ecstatic, and which can be seen, to a greater and more restrained degree, respectively, in the Gujarat genocide and the Old English text.

This is a violence, moreover, that can be understood to participate in what Dominick LaCapra, writing about the Holocaust, has described as a “deranged sacrificialism in the attempt to get rid of” stranger-Others as “phobic or ritually impure objects that polluted the Volksgemeinschaft (community of the people).”5 And to participate in this “deranged sacrificialism” is, according to LaCapra, to partake in a moment of Rausch—an elation, intoxication, delirium, or ecstasy—whereby “an unspeakable rite of passage involving quasi-sacrifice, victimization, and regeneration through violence” is undertaken as a labor of political culture.6 In the Gujarat massacre, which involved the mass sexual mutilation, torture, and brutal murder of hundreds of Muslim women, we can glimpse what Certeau terms the “latent singularity” that is “revealed in the continuous plurality of events”7 or what Paul Strohm calls the “traces or residues of an unexhausted past.”8 These are traces which join with the lines of the Old English text that describe Alexander’s killing of a race of giant “women who have boar’s tusks and hair ample to their heels and ox-tails on their loins,” because they were ‘shameful’ [æwisce] and ‘unworthy’ [unweorðe] ‘in their bodies’ [on lichoman].9 In both instances, the supposedly unruly and shameful bodies of women occasions a trauma in which, as Jeffrey Cohen argues, “[s]exed bodies are materialized along with the past in which they figure,” with women representing “the Real in all its inhuman, biological vitalism” and male heroes (who are also the founders of nations) signifying “the structurating principle that overcodes these obscenities of the flesh.”10

My yoking together of two widely disparate events—one terrifyingly real and the other purely textual, separated by approximately one thousand years and an entire continent—is admittedly somewhat contrived, although I must confess that my scholarly method is indebted to the aesthetic of the novelist W.G. Sebald, who sought in his writing to adhere to an “exact historical perspective” by “patiently engraving and linking together apparently disparate things in the manner of a still-life.”11 In an age that values speed and liquidity and synergistic conflation, it may be that one of the chief values of a medieval studies today would be in its ability to account, in slow and semi-still measure, for the phenomenology of what Cohen has defined as “the localized cultural matrix or meshwork,” which includes individual bodies, “within which time moves”12 and history is always becoming, going on, and returning.

I would also like to note here, before this essay progresses further, that while I agree with Michael Calabrese that “we cannot proceed uncritically in the pursuit of ethics as an attendant aspect of our studies of the medieval,” I do not agree that “all such criticism that foregrounds the history of violence and difference in an attempt to practice critical ethics risks reducing the text under study to a type of historical hate crime.”13 I disagree for two important reasons: first, because I understand violence to be a perduring feature of human nature and societies across time, I am not interested in assigning some kind of blame or moral repugnance to either characters in or authors and readers of medieval texts that represent fear of (and violence against) a particular group of persons, so much as I am interested in tracing circuits of anxieties that have always coalesced and continue to coalesce around the multiple histories of and contestations over becoming-human—the careful delineation of which histories and contestations by medieval and other scholars of premodern periods I see as critical to the future of humanism and the humanities; and second, I don’t see how we can possibly maintain what Calabrese terms “Arnoldian disinterestedness”14 over contemporary issues out of a fear for how the so-called corporate university might assimilate our politically sensitive scholarship in the service of global capitalism. Everything, ultimately, is up for grabs by global capitalism, including love and death, and while I agree with Calabrese that we should avoid adopting in our literary scholarship contrived political affects that are nothing more than postures, while also embracing an academic culture that is as open to as many competing viewpoints as possible, I ultimately concur with Françoise Meltzer that “the study of culture without politics is an inane undertaking,” although I would substitute “humanism” for her “politics.”15

Was this the India of my childhood? Were these my people?

In the roughly seventy-two hours between February 27th and March 2nd of 2002, there was a spectacular eruption of anti-Muslim violence in the southwestern Indian state of Gujarat that was partly a boiling over of long-simmering post-Partition tensions between Hindus and Muslims living there, but was also directly orchestrated by Hindu nationalist groups in collaboration with local political officials and police authorities.16 More specifically, the event was triggered by a fire-bombing on an express train pulling out of Godhra station on February 27th that was filled with mainly Hindu passengers returning home from a pilgrimage to Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, the supposed birthplace of the Hindu god Rama, a site that had become a kind of tinderbox for anti-Muslim sentiment. Fifty-eight passengers perished in the fire, and to this day it is not certain whether a Muslim mob throwing rocks at the train as it was departing the station or Hindu nationalists inside the train were responsible for the flammable substance that was either thrown into or poured within the car.17 What is certain is that in the days following, and fueled by local media and certain political officials allied with the Hindu nationalist right who sought to link the fire-bombing incident to Pakistani and international “Islamic” terrorism,18 a terrible wave of anti-Muslim violence seized the state. The attackers were gangs of young men armed with swords, explosives, chemicals, and trishuls (three-pronged spears associated with Hindu mythology), and the intention of the architects of this violence was clearly to make it appear as if it were the spontaneous riot of a “mob” of long-suffering “ordinary” Hindus no longer able to contain their rage against Muslim “outsiders.”19 When it was over approximately 2,000 Muslims—men, women, and children, the elderly and the infirm—were dead, many by being hacked with swords and then burned alive. Muslim mosques, businesses, vehicles, and homes were also defaced and destroyed, thereby creating a mass exodus of over 100,000 Muslims.

Most shocking of all were the mass rapes and sexual mutilation of the women, often staged in front of children who were made to watch and then killed afterward (or vice versa), in which the “typical tactic was first to rape or gang-rape the woman, then to torture her [primarily by mutilation of the genitals with metallic objects, such as swords, rods, and trishuls], and then to set her on fire and kill her.”20 Fetuses were ripped out of the wombs of pregnant women who were often also split down the middle with a sword and then burned. On some occasions, the breasts of the women were cut off; petrol was poured into the mouths of children, who were then exploded with lit matches; heads were cut off and displayed on platters to frighten those still alive; iron rods were used to electrocute children and to pierce young girls’ stomachs—to continue rehearsing these details is to risk entering the realm where, as one survivor put it, “I feel like my mind has been destroyed.”21

Although the violence in Gujarat left almost no Muslim body in the region untouched, the bodies of Muslim women and girls received special attention, and even, special violence. For the authors of the International Initiative for Justice’s feminist analysis of the massacres, the “scale and brutality of the sexual violence unleashed upon the women was new, or felt as if it was new,”22 and Flavia Agnes, a feminist legal activist, testified that the “scale and extent of atrocities perpetrated upon innocent Muslim women during the recent violence, far exceeds any reported sexual crime during any previous riots in the country in the post-independence period.”23 According to the historian Tanika Sarkar, who interviewed many of the eyewitnesses, “[t]he pattern of cruelty suggests three things. One, the woman’s body was a site of almost inexhaustible violence, with infinitely plural and innovative forms of torture. Second, their sexual and reproductive organs were attacked with a special savagery.”24

It was no accident that the violence in Gujarat reserved a special place for sexual sadism against Muslim women, for, as Martha Nussbaum has written, at the time of the massacres, Muslim female bodies symbolized “a recalcitrant part of the nation, one as yet undominated by Hindu male power,” and because the founders of the Hindu right in the 1930s borrowed much of their rhetoric and political culture from National Socialism in Germany and “openly expressed their sympathy with German ideals of racial purity,” a “very similar, and similarly paranoid, idea of male purity has taken deep root in the culture of the Hindu right, in a way that is unconnected to authentic Hindu religious and cultural traditions.”25 For Nussbaum, the critical importance of the operations of disgust in the Gujarat violence—especially in its sexual violence—cannot be underestimated, and also has to be understood in a more global context in which disgust has a long history as “a powerful weapon in social efforts to exclude certain groups and persons,” and in which history “the locus classicus of group-projected disgust is the female body.” Therefore, “[i]n very many cultures and times, women have been portrayed as dirt and pollution, as sources of a contamination that allures and must somehow . . . be both kept at bay and punished.”26 And because the woman’s body is a reproducing body, it occupies a precarious position within any community that considers itself a collective “nation,” one in which family is the basal unit.

Although it is clear that part of the campaign of rape of Muslim women was connected, on one level, to the making of “little Hindus” (in other words, to colonizing Muslim women’s bodies through impregnation), the Gujarat massacre was unique for the ways in which many of the rapes were inseparable from mutilation and murder (and therefore were decidedly not about colonization through impregnation), especially in light of the fact of how many women and girls were penetrated with metal objects and then also set on fire. The bodies of women have always, in the words of Anne McClintock, been “subsumed symbolically into the national body politic as its boundary and metaphoric limit.”27 Nevertheless, there was, in Sarkar’s words, a “dark sexual obsession”28 at work in the Gujarat genocide that could be said to pose an almost debilitating historical moment for global feminism, but also, more narrowly, for the idea of a secular and pluralistic India. For Uma Chakravarti, a feminist historian at Delhi University who participated on the International Initiative for Justice in Gujarat, the genocide was a kind of psychic deathblow:

I was a child of independent India, among the first generation of post independence children who had watched the nation being born on the midnight of August 14, 1947. . . .I despaired as I watched the horror of Gujarat unfold through its various stages. . . .Was this the India of my childhood? Were these my people?29

“Was this the India of my childhood?” and “Were these my people?” are questions worth lingering over. They point, I believe, to a moment of personal but also political crisis, as well as to a type of longing for something that has never been and can possibly never be—a polity that could align itself as a collective “body” under a name such as “India,” and in which name a radically liberal politics tied to that identity’s collective body could be articulated. Chakravarti’s plaint also gestures to a hope that a nation of “origin” could be predicated on something other than exclusion and violence. Chakravarti’s questions, which insist on one level that there is such a country as an independent India, a unity that could be capable of expressing a collective will and consciousness (implied to be humane, radically liberal, and incapable of violence), also cover over (or refuse to engage) the absence of history—similar to the Hindu right’s “pure” India, which they locate in an apocalyptic future tethered to the inheritance of an ancient “holy land,”30 Chakravarti’s nation born on the midnight of August 14, 1947 never existed, or has yet to arrive, except as an event-to-come. This is not to say that there is no history in India (although some have claimed so),31 but rather, that the matter of India having a history as “India,” however defined, is always an open question that must address itself not only to the context of what Eric Hobsbawm has termed the “exclusively” and “historically recent” nation (or, “modern territorial state”),32 but also to the context of the premodern world in which ideas of “peoples” (gentes) were always tied to particular physiognomies and geographies, and where, to paraphrase Roger Bacon, place was always the beginning of existence.33

A moment of unraveling transference.

The tenth-century Old English text, The Wonders of the East (British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fols. 98v–106v),34 an early pictorial catalog of monstrous bodies and animal and human marvels is not typically considered a romance narrative—indeed, Mary Campbell has argued that the Wonders is a text that “records a mass of unsynthesized data shorn of any relation to an experiencing witness.”35 Susan Kim believes that it is “difficult to discern any consistent method behind the organization of the catalog,”36 and Asa Simon Mittman argues that the text’s “accounts of various human, animal and plant oddities are disconnected, discontinuous descriptions” which, extracted from their exemplar’s epistolary framework, are “extracted and essentialized”—“little ethnographical and zoological morsels, easily consumable individually or all together.”37 In some respects, the Old English Wonders, a text that is derived from Latin and Greek sources on travels to the East that have been filtered through Continental translations over a period of hundreds of years before being made over into a local vernacular in an Anglo-Saxon manuscript, functions somewhat like a cabinet of curiosities, or more properly, a collection that, in Susan Stewart’s words, “seeks a form of self-enclosure which is possible because of its ahistoricism. The collection replaces history with classification, with order beyond the realm of temporality.”38

The Wonders then, lacks what could be called a linear or other type of explicit narrative structure—it cannot even, properly speaking, be called an ordered or orderly series, progressing, say, from plants to animals to “humans” (in that sense, even if it’s a collection, it’s an unruly one). Nevertheless, by virtue of Alexander’s sudden appearance toward the end of the text as the executioner of a race of thirteen-feet-tall and white marble-bodied “women who have boars’ tusks and hair ample to their heels, and ox-tails on their loins,” as well as “camel’s feet and boar’s teeth” (sec. 27, p. 200), I want to suggest that the Wonders text is stitched to the one that follows it in the Nowell codex of the Vitellius A.xv manuscript, the Old English Letter of Alexander to Aristotle, and therefore the Wonders is subsumed into the long-established corpus of Alexandrian romance. In the Old English Letter, Alexander tells his old teacher Aristotle that his ‘memory’ [gemynd], which is also his ‘mind’ and his ‘memorial’ in the form of all the letters and monuments he leaves behind, should “stand and loom perpetually as an example for other earthly kings, so that they [will] know very well that my might and my honor were greater than all of the other kings who ever were in the world” (sec. 41, p. 252). In this sense, Alexander’s killing of the giant human-animal women in the Wonders participates, if even tangentially, in the genre of medieval romance, in which, as Cohen writes, “[t]he defeat of the giant is a social fantasy of the triumph of the corporeal order (in all its various meanings) written as a personal drama, a vindication of the tight channeling of multiple somatic drives into a socially beneficial expression of masculinity.”39

Although The Wonders of the East exists in three manuscripts of medieval English provenance, dating from the tenth through twelfth centuries, I am concentrating my analysis primarily on the Vitellius version of Wonders as that is the earliest copy in English and also because, in addition to sharing the Nowell codex with the Old English Letter of Alexander to Aristotle, it also shares that space with Beowulf, which follows the Letter. Following the thinking of Nicholas Howe, I consider the Nowell codex as a “cultural atlas” that, “by depicting regions in continental Europe, the Middle East, and Asia,” may have established for its Anglo-Saxon audience “a vivid, expansive, and sometimes cautionary sense of place.”40 The savvy client-reader of the Anglo-Saxon monastic library would have likely recognized from other manuscripts on the shelves many of the marvels recorded in the Wonders, such as the men without heads whose eyes and mouths are in their chest (the Blemmyae) and the dog-headed men (the Conopenae), but by virtue of these marvels’ enclosure within the vernacular language and because early medieval maps positioned the British Isles at the furthest margins of the world—often in the same outermost band that contained the monstrous races of Africa—the Anglo-Latin Wonders tradition might have constituted an already known but discomforting arrangement, one in which monsters and the English shared an uneasy geography.41 This discomfort would have been augmented by the illustrations which, “particularly in the Vitellius version,” as Kim has argued, “are characterized by their aggressive and persistent movement outside their frames, and even . . . by their invasion of the textual space.”42

I further agree with Howe that the texts in the “cultural atlas” of the Nowell codex also “form a compilatio in the sense that Martin Irvine uses the term: ‘the selection of materials from the cultural library so that the resulting collection forms an interpretive arrangement of texts and discourse’.”43 While we cannot say for certain how the texts in the Nowell codex—none of which are actually set in England—might have functioned as part and parcel of, say, a post-Alfredian program of nation-building, we can certainly identify the social context of the codex’s assembly, as Brian McFadden does, as one that was rife with “anxieties caused by tenth- and early-eleventh-century Viking Invasions, the Benedictine Reform, and eschatological concerns provoked by the coming millennium,” such that the Old English works gathered together in this compilatio could be viewed as highlighting different forms of “resistance of foreign others to containment in either a social or narrative order.”44

Although Alexander’s killing of the giant human-animal women in the Wonders can certainly be understood as having participated in a certain romantic (and violent) poetics of nation-building in which, in Cohen’s words, “bodies that do not know their proper cultural place because they preexist the masculine ‘invention’ of place” have to be evacuated,45 this act of sudden and unanticipated aggression, although it is certainly consistent with Alexander’s reputation as a world conqueror, has to also be considered as a somewhat anomalous event within the Wonders itself, and even in relation to the text of the Letter that follows. In the case of the Wonders text, there is, with one other exception [the “barbarous peoples” of sec. 18], almost a complete and total absence of any kind of moral condemnation of the monstrous animals and animal-human creatures and other races, not even where you might expect it most—in the case, say, of the polyglot and anthrophagic Donestre who beguile strangers by talking to them in their familiar language and then kill and eat them, except for the heads, over which, afterwards, they ‘sit and weep’ (sec. 20, p. 196),46 an image that could almost be said to construct a moment of pathos for the Donestre who seem caught in an inexorable cycle of consuming their own abject humanness. In addition, the text even praises a group of ‘benevolent’ [fremfulle] people who, “if any man goes to them they give him a woman before they let him go away” (sec. 30, p. 200). This passage is significant because it sets up Alexander’s only other interruption of the text as an active character: the author tells us that when Alexander visited these people, “he was astonished at their humanity, and he would not kill them nor cause them any injury” (sec. 30, p. 202). The only other mention of Alexander in the text is at the very beginning, where it is mentioned that in the land of Archemedon there are ‘great monuments’ [mycclan mærða] which “the great Macedonian Alexander commanded to be made” (sec. 2, p. 184). From this moment forward, Alexander’s presence could be said to hover over the Wonders text as an absent yet still imposing force who suddenly appears, in a vigorously present past tense, as the executioner of the giant women whom, we are told, he could not capture alive [“he hi lifiende gefon ne mihte”; sec. 27, p. 200], indicating their position outside any epistemology of knowledge or technique of subjugation: they are “disturbing hybrids whose externally incoherent bodies resist attempts to include them in any systematic structuration.”47 They can be killed, but they cannot be caught (known), which might be another way of saying, they cannot be penetrated in the same way that Alexander penetrates, in the Letter, the innanwearde [‘innermost part’] of India (sec. 9, p. 228).

Although the Alexander of classical and medieval legend, much like the Hercules of the Liber Monstrorum, “traveled in battles through almost the entire world, and spattered the earth with so much blood” [“paene totum orbem cum bellis peragrasset et terram tanto sanguine maculauisset”; sec. 12, p. 267], the Alexander of the Letter seems more intent on ‘beholding’ [sceawigað] the spectacle of ‘wondrous creatures’ [wunderlice wyhta; sec. 3, p. 226] than he is on killing them, unless they attack first. This is the case when a great multitude of Cynocephali (dog-headed men) emerge from the woods with the intent of harming Alexander and his men, to which they respond by shooting them with arrows until they “departed back into the forest” (sec. 29, p. 224). This is not to say that the Alexander of the Letter is a somehow gentler, kinder Alexander—far from it. He mentions several battles with foreign armies (there is no kingdom he is not intent on subduing), and he often vents his violent fury at those who serve under his command. After a harrowing night spent at a lake battling hordes of attacking animals, even though he himself had requested that his guides take him by the dangerous and not the safe paths (sec. 9, p. 228), he orders that the guides who led him to such travails be “tied up and their bones and legs broken, so that they would be swallowed in the night by the serpents” (sec. 22, p. 238). But when it comes to certain monstrous “peoples,” who are more like local tribes or sub-populations within the kingdoms Alexander is always seeking to topple and absorb as part of his world-becoming trajectory, he seems more intent on what might be called scientific observation than murder and conquest. In the case of the nine-feet-tall naked women and men who are as “shaggy and hairy as wild beasts,” and who can snatch whales out of the rivers and eat them, Alexander writes that he wanted to take a closer look and observe them, but they “immediately fled into the water and hid themselves in stony hollows” (sec. 29, p. 242). This Alexander—the explorer and seeker of marvels who desires to see the innermost parts of India and who often lets strange creatures run away without pursuing them to the death—provides a striking contrast to the Alexander of the Wonders who kills the thirteen-foot-tall women “on account of their giant-ness” [for heora micelness],48 because he could not capture them alive, and because they are “shameful and unworthy in their bodies.”

It has to be admitted that the Alexander of the Wonders who would kill an entire race because he could not capture one (or more) of them was likely very recognizable to an Anglo-Saxon audience familiar with the Alexander of the Old English Orosius who is described there as se swelgend—according to Bosworth-Toller, ‘voracious person’ or ‘glutton,’ but also, more fittingly in this case, ‘a place which swallows up, a very deep place, an abyss, a gulf, a whirlpool.’49 In some of the many Continental texts that likely served as exemplars in the transmission of manuscripts leading to the Anglo-Latin Wonders, and which still retain something of the original epistolary framework of the Letter of Pharasmanes (which pointedly does not include mention of the murder of these women, who are described, for all of their animal characteristics, as specioso corpore, ‘beautiful in their bodies’), it is remarked that, “The writer desired to look at them, [and] some were killed by three of our comrades because they could not capture them alive.” In one manuscript, it indicates that the women fought for a long time and were able to escape.50 Because the Old English text simply states, in two instances, hie gefelde wurdon and acwealde he hi [‘they were killed’ and ‘he killed them’; sec. 27, p. 200], Alexander therefore killed the entire tribe, or at least whoever of that tribe was visible to him and within reach (although it is amusing to speculate how Alexander killed a entire tribe, or race, of women whom he supposedly could not capture—the implication would seem to be that this tribe of women were such violent fighters that they could not be subdued without retaliatory violence of equal force, or else they were excellent runners and had to be shot down with arrows). In the Latin text included in the Tiberius and Bodleian manuscripts, we are told, “many of them were killed” [multae ex ipsis ceciderunt].51 Therefore, by the time the Wonders text gets transcribed into three Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, the number of women killed is either “all” or “many,” indicating not the sport of hunting one or two of an exotic species but the wholesale slaughter of a group. Nevertheless, within the created world of the Wonders text, which seems mainly constructed around objective and non-judgmental scenes of fleeting glimpses of foreign Others (and within which scenes, many of the creatures are even described as “shy” or “soft-voiced” and “hospitable” and so afraid of intruders they run away when approached), this slaughter is striking in its sudden violence that literally appears from somewhere else (the tradition of Alexandrian romance), and yet could almost be argued to have been called forth by the women’s unruly and shameful and perhaps too-masculine and hypersexual bodies.

Because we know that there are many bodies in the Wonders text that combine human and animal features, yet do not require violent elimination (including the men who give birth in sec. 11), what sets these women apart might be said to be their first-introduced characteristic: they are wif [‘women’] first of all, and ‘woman’ is a term that, historically, has always marked the terrain of the too queer. As Elizabeth Grosz writes,

The metaphorics of uncontrollability, the ambivalence between deep, fatal attraction and strong revulsion, the deep-seated fear of absorption, the association of femininity with contagion and disorder, the undecidability of the limits of the female body . . , its powers of cynical seduction and allure are all common themes in literary and cultural representations of women.52

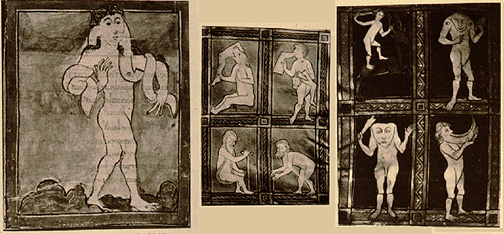

The readers of the Old English Wonders, similar to the fictional Alexander himself, may very well have been drawn to the image of these women as both frightening and attractive, and there may have even been some cognitive dissonance, leading to feelings of both sexual desire (or sexual astonishment), followed by feelings of violent revulsion, the relief of which (through dark enjoyment) might have been provided by Alexander’s decisive act of execution. The illustrations in the Vitellius and Tiberius manuscripts actually bear out this idea of cognitive dissonance wrought by the description of the women in the text. According to Kathryn Powell, whereas the Tiberius illustrator sought to minimize the animal characteristics (the hooves and tusks are present, but quite small) and to emphasize the woman’s beautiful and slender naked body (which is modestly covered by her long hair, but revealing enough to be enticing, albeit lacking any hint of breasts and therefore androgynous), the Vitellius illustrator emphasizes a figure “who is only recognizable as a woman by virtue of her partially exposed breasts” and who is thick and muscular and intimidating in her giant-ness.53 Further, as Dana Oswald has described the Vitellius illustration, the body parts are “exaggerated”: “Her lips are extremely full, and perhaps even red, unlike any other figure in the manuscript. Her breasts are bulbous and reach down to the split of her legs, all of her sexual parts thus seeming to incorporate one another.” Conversely, in the Tiberius illustration, the artist “seems to be at pains to simultaneously conceal and reveal this body . . . . Though the woman’s chest faces us, she crosses her arms across it, curling her fingers around the locks of hair on either side of her torso.” Further, “[t]he hair cascades over her rotated hips, flowing around her exposed buttocks, and between the cross of her legs.”54

Interestingly, the figure judged most “feminine” (Powell) and “delicate” (Oswald) in Tiberius, combines both conventionally feminine (curved hips and buttocks and long flowing hair) and conventionally masculine (no breasts, boy-like torso) features—if this woman is attractive, it is partly because her physiognomy is androgynous, or at least bi-sexed, whereas the woman drawn in the Vitellius manuscript is threatening precisely because the markers of her female-ness (her breasts) are so large, so monstrously out of proportion. In addition, whereas the woman in Tiberius is positioned fully within the frame and turning away to the right—as if departing or getting ready to flee—the woman in Vitellius is standing with her full body facing forward, her head and hooves extending outside of the frame, and is holding a tri-pointed scepter (or club), making her even more frightening in her imperiousness. To be monstrous in this scenario is not so much to be a mixture of mismatched human and animal body parts (gendered and otherwise) as it is to be too much of one thing: wif, or ‘woman,’ while also striking a proudly aggressive pose.

But there is something more, too, in both of these illustrations that points to the discomfort both illustrators may have felt when drawing this woman’s body: the ‘ox-tail’ [oxan tægl], which very clearly, according to the text, is attached ‘on the loins’ [on lendenum].55 As Ann Knock has pointed out, the compiler of the tenth-century Liber Monstrorum (believed by both Knock and Orchard to have used the Latin Wonders as one of his sources) was squeamish enough about this detail to change in lumbis [‘on the loins’] to the euphemistic in lateribus [‘on the side or flank’]. Although the Tiberius illustrator had the Latin in lumbis and Old English on lendenum right in front of him (although, admittedly, he may have been following an exemplar illustration and not the text), he chose to place the tail directly on the woman’s left posterior, near the anus, where it is more animal-like and less sexual. In the Vitellius illustration it is difficult to determine at first if the ox-tail is even present, but if you examine the image carefully, it is clear that the tail is present, protruding from the woman’s right leg, near her hip, and curving downward behind her leg, near the knee, where it joins the long hair flowing behind her back. The outlines of this tail, at the top, stray dangerously close to where the woman’s breasts meet her genital area. Because the illustrators for both manuscripts clearly chose to revise the textual directions for the placement of the ox-tail, it would appear they had some anxiety about this feature of the image, and sought to subtly revise it. As Oswald writes, the bodies of these women “imply a kind of action that is far more transgressive than just exceeding human norms. This action is communicated through the possession of a tail, but even more explicitly through the rupture between the artists’ rendering of the tail and the writers’ words describing it.”56

The race of women with ox-tails on lendenum may have presented, both for the readers of the manuscript as well as for the fictional Alexander and the author who created him in language, an image of a figure too perverse, too abject, which, in Kristeva’s words, “takes the ego back to its source on the abominable limits from which, in order to be, the ego has broken away.”57 In this scenario, Alexander’s murder of the animal-human dyads would be the natural outcome of Alexander’s (and the author’s) sudden recognition of the fragility of the subject’s “own and clean self,”58 which would need to be purified by some violent means. That an Anglo-Saxon readership could have understood such a notion is well explained by Powell, who has analyzed this instance of literary extermination in the Wonders text alongside the St. Brice’s Day Massacre of 1002, when, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records, “the king [Æthelred] commanded that all the Danish men who were among the English be slain . . . because the king was informed that they wished to ensnare his life, and afterwards all of his counselors, and afterwards have this kingdom.”59As regards the severity of the attacks, a charter of 1004 from the monastery of St. Frideswide at Oxford records that a certain group of Danes, who had “sprung up” in England like “cockle amongst the wheat,” had been forced to flee to the barred church, the doors and bolts of which they broke by force to get inside, and once securely settled there, an angry mob of their neighbors set fire to the church, apparently burning the Danes inside, along with “its ornaments and books.”60 As Powell writes, “The behavior of the Anglo-Saxons on St. Brice’s Day suggests that the Danes had become for the English a homogeneous Other who existed solely to deprive them of their every enjoyment—life, land, wealth, and power—and who were unworthy of human sympathy.”61

We might recall here that in the image of the giant women of the Wonders in the Vitellius manuscript, that they are holding what looks to be a type of scepter (or club), an object that would have denoted some type of threatening power for the audience of the manuscript (although no such detail is mentioned in the Old English text). And this threatening strength could have only been complicated by the gender of its wielder, which might have rendered the image both frightening and attractive simultaneously. As Powell explains, the Old English word æwisce [‘shameful’], used to describe the women’s bodies, “is sometimes used to describe female temptresses, most notably of Eve in Genesis, who is called ‘ides æwiscmod’ [ashamed woman; line 896] after she has enticed Adam to eat the forbidden fruit.”62 The image in the Vitellius manuscript, as well as the Old English text that accompanies it, would appear to work together to construct a moment of “unraveling transference . . . of love/hatred for the other,”63 leading to definitive act of “ecstatic destructiveness” which, in the terms set forth by Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit, reading Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents, is “ultimately unanalysable”:

It can’t be interpretively reduced or reformulated; individual histories are irrelevant to it, as is perhaps history tout court . . . . It is postulated as a universal property of the human psyche, something as species-specific as the human aptitude for verbal language. . . . Jouissance is without psychological causation; it is the final cause of our desires, the cause (in Lacanian terms) to which no object of our desire ever corresponds.64

But if jouissance—this dark enjoyment that threatens individuals and whole societies—is a pleasure “beyond pleasure” (in Lacan’s terms), can there be a jouissance beyond jouissance, something that might, in the words of Bersani and Dutoit, “play to the side of it, supplement it with a pleasure at once less intense and more seductive”?65 How to move beyond, or to the side, of the dark poetics of cultural identity in which the figures of unimpregnable and hypersexual female bodies have to be violently evacuated while also being instituted as a sacred-obscene threshold to natio (?), much like the Egyptian Danaïdes of ancient Greek legend whose aggressive refusal to marry their cousins led to their exile in Argos and then their execution, with the eternal punishment of bearing water in jars perforated like sieves to a bottomless cistern.

An otherness barely touched upon and that already moves away.

Although we know from both the Latin and Old English texts of the Anglo-Saxon Wonders that Alexander ‘killed’ [ceciderunt and acwealde, past tense] many or all of the giant women with ox-tails on their loins, this threatening race of women are first introduced to the reader in the present tense—“Then there are other women who have boar’s tusks” [“Ðonne sindon oðre wif ða habbað eoferes tucxas . . .”]—and therefore they are always simultaneously killed and still palpably out there somewhere, threatening the reader in their monstrous present-ness. Indeed, in all the moments of reading this Old English text, past and present, these women haunt history as still there, still too queer, too unsubordinated, and always looming, dangerously, in their unruly sexuality which threatens to collapse the border between same and different, self and Other. Moreover, these fictional women stand alongside the real women who were mutilated and murdered in Gujarat, where together they mark the place, which is also the boneyard, of something that has always been an ineluctable fact of human existence: the essential volatility of bodies, of biology and culture, and of the fear, loathing, and hatred this impassable condition of history calls forth. And the ethical task that this imposes on us, in Kristeva’s formulation, would be to “not seek to solidify, to turn the otherness” of these bodies “into a thing,” but to merely “touch it, brush by it, without giving it a permanent structure.” This would be the very otherness that the Wonders texts, amazingly, in its grammar, has already inscribed for us and invites us to marvel at—one that is “barely touched upon and that already moves away.”66

As Bersani and Dutoit argue, if there is to be “a jouissance beyond jouissance,” we must overcome “the illusion of disconnectedness,” an illusion which “makes of the external world . . . an always potentially dangerous enemy of the self.” Since “jouissance ‘rewards’ the illusion of having abolished the distance, and the difference, between the subject and the world,” perhaps the alternative “dark enjoyment” would be to allow ourselves to be so “extraordinarily receptive to the being of the world,” that even in the midst of war and slaughter itself, in a willed moment of “ontological passivity,” of marveling and wondering at the shining strangeness of the world, we could be “shattered by it . . . shattered in order to be recycled as allness.” This shattering of our individual identities in a “wholly open looking” at the “world as correspondences” might be our “truest human ripeness,”67 as well as an ecstasy that would lose itself in a marvelous relationality without discernible borders. In this scenario, there would be no nations, no city-states, and no heroic individuals, only wonders.

Endnotes

The completion of this essay would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the Newberry Library Center for Renaissance Studies, who funded my travel to the Library in winter 2007 to participate in Susan Kim’s Graduate Consortium Seminar, “Unworthy Bodies: The Other Texts of the Beowulf Manuscript.” My thanks also to Dana Oswald for generously sharing portions of her dissertation with me while it was still in progress.

1 Michel de Certeau, The Possession at Loudon, trans. Michael B. Smith (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972), p. 227.

2 Certeau, The Possession at Loudon, p. 1.

3 Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), p. 203.

4 William Ian Miller, The Anatomy of Disgust (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 204.

5 Dominick LaCapra, History and Memory After Auschwitz (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), p. 38.

6 LaCapra, History and Memory After Auschwitz, p. 29 n. 19; see also Saul Friedlander, Memory, History, and the Extermination of the Jews (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), pp. 109–15.

7 Certeau, The Possession at Loudon, p. 1.

8 Paul Strohm, Theory and the Premodern Text (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p. 93.

9 Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 1995), sec. 27, p. 200. Citations of the Old English and Latin Wonders, the Old English Letter of Alexander to Aristotle (contained in the Vitellius A.xv manuscript), as well as to the Liber Monstrorum, will be to Orchard’s editions of these texts, which are included as appendices in Pride and Prodigies, parenthetically, by section and page numbers. All translations, unless otherwise noted, are mine.

10 Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Of Giants: Sex, Monsters, and the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), pp. 46 and 49.

11 W.G. Sebald, “An Attempt at Resitution,” trans. Anthea Bell, The New Yorker 20 & 27 December 2004: 112 [110–14].

12 Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Medieval Identity Machines (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2003), p. 9.

13 “Performing the Prioress: ‘Conscience’ and Responsibility in Studies of Chaucer’s Prioress’s Tale,” Texas Studies in Language and Literature 44.1 (Spring 2002): 69 [66–91].

14 Calabrese, “Performing the Prioress,” p. 71.

15 Françoise Meltzer, “Future? What Future?” Critical Inquiry 30 [2004]: 469 [468–71].

16 For a full accounting and analysis of the details of the Gujarat genocide and its aftermath, see International Initiative for Justice-Gujarat (IIJ), Threatened Existence: A Feminist Analysis of the Genocide in Gujarat, December 2003, available at http://www.onlinevolunteers.org/ gujarat/reports/ iijg/2003/ (hereafter referred to as Threatened Existence); Smita Narula, Jonathan Horowitz, Amardeep Singh, et al., “We Have No Orders to Save You”: State Participation and Complicity in Communal Violence in Gujarat, Human Rights Watch Reports 14.3(C) (April 2002): 1–68, available at http://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/india/ (hereafter referred to as We Have No Orders); and Siddharth Varadarajan, ed., Gujarat: The Making of a Tragedy (New Delhi, India: Penguin Books, 2002).

17 For a full accounting of the Ghodra incident, see Jyoti Punwani, “The Carnage at Ghodra,” in Varadarajan, Gujarat: The Making of a Tragedy, pp. 45–74. See also Martha Nussbaum, The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), pp. 33–36.

18 On this point, see Siddharth Varadarajan, “Chronicle of a Tragedy Foretold,” in Varadarajan, Gujarat: The Making of a Tragedy, pp. 5–10 [3–41].

19 On this point, see Nandini Sundar, “A License to Kill: Patterns of Violence in Gujarat,” in Varadarajan, Gujarat: The Making of a Tragedy, pp. 75–134.

20 Martha Nussbaum, “Body of the Nation: Why Women Were Mutilated in Gujarat,” The Boston Review 29.3 (2004), http://www.bostonreview.net/BR29.3/Nussbaum.html. See also Martha Nussbaum, “Genocide in Gujarat: The International Community Looks Away,” Dissent (Summer 2003): 61–69.

21 Testimony of Javed Hussain, fourteen-year-old survivor of the Gujarat massacre; quoted in “Narratives from the Killing Fields,” in Varadarajan, Gujarat: The Making of a Tragedy, p. 138 [135–76].

22 Threatened Existence, p. 8.

23 Flavia Agnes, “Affidavit,” in Of Lofty Claims and Muffled Voices, ed. Flavia Agnes (Bombay, India: Majlis, 2002), p. 69.

24 Tanika Sarkar, “Semiotics of Terror: Muslim Women and Children in Hindu Rashtra,” Economic and Political Weekly 13 July 2002: 2872–76; quoted in Threatened Existence, p. 26.

25 Nussabaum, “Body of the Nation.”

26 Nussbaum, Hiding from Humanity, p. 112.

27 Anne McClintock, “‘No Longer in a Future Heaven’: Gender, Race, and Nationalism,” in Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives, ed. Anne McClintock, Aamir Mufti, and Ella Shohat (Minneapolis: University Press, 1997), p. 90 [89–112]. See also Nira Yuval-Davis and Floya Anthias, eds., Women-Nation-State (London: Macmillan, 1989), and Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest (New York: Routledge, 1995).

28 Sarkar, “Semiotics of Terror”; quoted in Nussbaum, “Body of the Nation.”

29 Quoted in Threatened Existence, p. 8.

30 On the Hindu right’s fascist historicizing, see Threatened Existence, pp. 17–24.

31 See Gyan Prakash, “Postcolonial Criticism and Indian Historiography,” in McClintock et al., Dangerous Liaisons, pp. 491–500, where he writes that “[h]istory and colonialism arose together in India. As India was introduced to history, it was also stripped of a meaningful past; it became a historyless society brought into the age of History” (p. 499).

32 E.J. Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationality Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 9. I am well aware of the extensive work undertaken in medieval studies to revise Hobsbawm’s idea of the nation-state as exclusively modern; on this point, see especially Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Introduction: Midcolonial,” in The Postcolonial Middle Ages, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), pp. 1–17; Kathleen Davis, “National Writing in the Ninth Century: A Reminder for Postcolonial Thinking about the Nation,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 28 (1998): 611–37; Bruce Holsinger, “Medieval Studies, Postcolonial Studies and the Genealogies of Critique,” Speculum 77 (2002): 1195–227; and Ananya Jahanara Kabir and Deanne Williams, “Introduction: A Return to Wonder,” in Postcolonial Approaches to the European Middle Ages: Translating Cultures, ed. Ananya Jahanara Kabir and Deanne Williams (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 1–21.

33 The full quotation is, “Place is the beginning of our existence, just as a father” (Roger Bacon, The Opus Majus of Roger Bacon, trans. Robert Belle Burke [New York, 1962], p. 159).

34 The Wonders of the East survives in three richly illustrated copies in medieval English manuscripts: in Old English in British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv (fols. 98v–106v), dating to the late tenth century, in Old English with facing Latin in British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.v (fols. 78v–87r), dating to the eleventh century, and in Latin in Oxford, Bodleian Library (fols. 36r–48r), from the twelfth century. According to Andy Orchard, the Anglo-Saxon versions of the Wonders “derive ultimately from a text represented in mainly continental manuscripts in many different forms, almost all of which share a basic epistolary framework, in which either a character variously named Feramen, Feramus, or Fermes writes to the emperor Hadrian (A.D. 117–38), or a figure called Premo, Premonis, Perimenis, or Parmoenis writes to Hadrian’s predecessor, the Emperor Trajan (A.D. 98–116), to report on the many marvels he has witnessed on his travels” (Pride and Prodigies, pp. 22–23).

35 Mary Campbell, The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400–1600 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988), p. 82.

36 Susan Kim, “The Donestre and the Person of Both Sexes,” in Naked Before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Benjamin C. Withers and Jonathan Wilcox (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2003), p. 165 [162–80].

37 Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England (New York and London: Routledge, 2006), p. 80.

38 Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993), pp. 151 and 152.

39 Cohen, Of Giants, p. 84.

40 Nicholas Howe, “Historicist Approaches,” in Reading Old English Texts, ed. Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 93 [79–100]. See also Martin Irvine, The Making of Textual Culture: ‘Grammatica’ and Literary Theory, 350–1100 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994), especially pp. 272–460).

41 On this point, see Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England, pp. 39–59; Kathy Lavezzo, Angels on the Edge of the World: Geography, Literature, and English Community (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006), pp. 27–31; and Martin K. Foys, “The Virtual Reality of the Anglo-Saxon Mappamundi,” Literature Compass 1 (2003): n.p. [online journal]; available at http://www.literaturecompass.com.

42 Susan M. Kim, “Man-Eating Monsters and Ants as Big as Dogs: The Alienated Language of the Cotton Vitellius A.xv Wonders of the East,” in Animals and the Symbolic in Medieval Art and Literature, ed. L.A.J.R. Houwen (Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1997), p. 40 [38–51].

43 Howe, “Historicist Approaches,” 95.

44 Brian McFadden, “The Social Context of Narrative Disruption in The Letter of Alexander to Aristotle,” Anglo-Saxon England 30 (2001): 91 [91–114].

45 Cohen, Of Giants, p. 59.

46 The black cannibals, with long legs and feet [sec. 13] might be considered another, albeit minor, instance of negative approbation on the author’s part since their name, hostes, means ‘enemy.’

47 Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Monster Culture (Seven Theses),” in Monster Theory: Reading Culture, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), p. 6 [3–25].

48 The Latin text of the Tiberius and Bodleian manuscripts indicates obscentitate [obscenity], where the Old English translator has mycelnesse and micelnesse, respectively [giant-ness]. In his edition, E.V. Gordon emended this to unclennesse (“Old English Studies,” The Year’s Work in Old English Studies 5 [1924]: 66–72), an emendation Orchard follows in his edition. Although it may well be true that the compiler of the Old English Wonders made a mistake in copying unclennesse, I would argue that micelnesse is an apt substitute for the description of women who are thirteen-feet-tall, and we do not lose the meaning of their ‘obscene’ bodies since the Old English translation still retains the phrase “æwisce on lichoman 7 unweorðe” [“shameful and unworthy in (their) bodies”].

49 Janet M. Bately, ed., The Old English Orosius, EETS s.s. 6 (London: Oxford University Press, 1980), 66.7.

50 See Ann Knock, “Wonders of the East: A Synoptic Edition of the Letter of Pharasmenes and the Old English and Old Picard Translations,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of London, 1982,” pp. 749–62.

51 Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, p. 180.

52 Grosz, Volatile Bodies, p. 203.

53 Kathryn Powell, “The Anglo-Saxon Imaginary of the East: A Psychoanalytic Exploration of the Image of the East in Old English Literature,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Notre Dame, 2001,” p. 151.

54 Dana Oswald, “Indecent Bodies: Gender and the Monstrous in Medieval English Literature,” Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, 2005.

55 Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, sec. 27, p. 200. This is borne out in the Latin version of the Wonders text found in the Tiberius and Bodleian manuscripts, where we find in lumbis caudas boum. It is further significant that, in classical Latin, caudas can often stand in for ‘penis.’

56 Oswald, “Indecent Bodies.”

57 Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), p. 15.

58 Kristeva, Powers of Horror, p. 53.

59 Rositzke, Harry August, ed., The C-Text of the Old English Chronicles (Bochum-Langendreer: Heinrich Pöppinghaus, 1940), pp. 55–56. According to Simon Keynes, Æthelred’s order was likely not directed against the Danes who were already well-established for over a hundred years in the Danelaw and therefore were fully assimilated, but rather was probably “directed against the Danes who had recently settled in various parts of England, whether as traders, as mercenaries, or even simply as paid-off and provisioned members of the armies that had been ravaging the kingdom” (The Diplomas of King Æthelred the Unready, 978–1016: A Study in Their Use as Historical Evidence [Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1980], p. 204).

60 Dorothy Whitelock, ed., English Historical Documents I, c. 500–1042, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), p. 591.

61 Powell, “The Anglo-Saxon Imaginary of the East,” p. 157.

62 Powell, “The Anglo-Saxon Imaginary of the East,” p. 160.

63 Kristeva, Strangers to Ourselves, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), p. 182.

64 Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit, Forms of Being: Cinema, Aesthetics, Subjectivity (London: British Film Institute, 2004), pp. 126–27.

65 Bersani and Dutoit, Forms of Being, p. 127.

66 Kristeva, Strangers to Ourselves, p. 3.

67 Bersani and Dutoit, Forms of Being, pp. 175–76, 177.