Eileen A. Joy, Assoc. Professor

Department of English

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

ejoy@siue.edu

http://www.siue.edu/~ejoy

CHAPTER ABSTRACT:

For: The Politics of Nothing: Sovereignty and Modernity, eds. Clare Monagle and Dimitris Vardoulakis

Notes Toward an Anglo-Saxon Biohistory

In our current, supposedly “post/human” age, intellectual work on biopower and biotechnologies has become intense, beginning with Foucault’s commentary in the first volume of History of Sexuality on “Right of Death and Power Over Life,” where he argued that the premodern sovereign’s authority to “take life or let live” had been superseded in modernity by a disciplinary biopolitics that “fosters” or “disallows” life. Although the Nazi regime, with its merging of the “old” sovereign power to take life and an intense biopolitics that also reduced and disallowed some lives, troubled Foucault’s analysis of modern biopower, he still insisted on a linear biohistory. When Agamben proposed the biopolitical principle through his delineation of bios and zoe in ancient Greek society, and later, of homo sacer and the sovereign exception in the Roman empire, medievalists started tracking the possibilities for modifying Foucault along these lines. But as Kathleen Biddick has been pointing out in her recent work on medievalism, political theology, and contemporary theories of sovereignty[1], the disappointing part of Agamben’s account of biopolitics is that, although he “argued for biopower as the kernel of power from the ancient world to the present,” he did so by also proposing a temporality (messianic time) informed by typological relations (littera to figura) that he was at pains to “bracket off” from medieval forms of typology, and therefore, as Biddick has elegantly argued, Agamben’s “messianic time becomes haunted by an inexplicable amputation.” In the end, both Foucault and Agamben immunize biopower from the medieval.

In some recent talks she has given (relative to her ongoing book project, The Tears of History), Biddick has beuatifully detailed some of the ways in which “new epistemologies of flesh, time, law and biopolitics [were] emerging among clerical circles . . . in early twelfth-century Anglo-Norman England,” and how “liturgical bare life,” as well as the “suture of Eucharistic and Jewish flesh,” form “the biopolitical kernel at the heart of sovereign legal innovations” in the medieval period. Rather than re-assert some sort of linear temporality whereby medieval political history becomes one more important step along the way to modern biopower, Biddick insists instead on “transcryptic” accounts, where past moments of biopower become traumatic sites that are “buried” in the present, yet still travel (are transitive), haunting and troubling accounts of a supposedly linear, thoroughly “modern,” and secular biohistory.

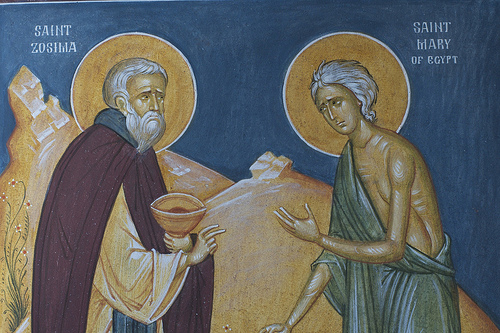

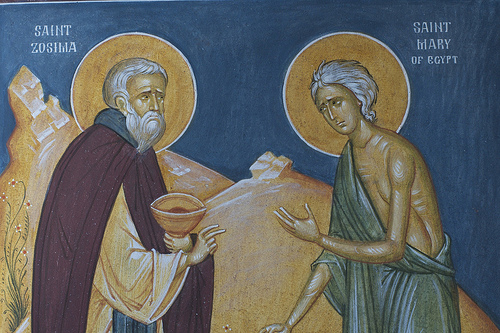

My commentary will ask where we might begin to trace similar traumatic sites in the Anglo-Saxon historical (and literary) record, and I will suggest some initial starting points, vis-a-vis the tropes/figures of the stranger/foreigner, sovereignty, flesh, and “bare life” in Anglo-Saxon law codes and in hagiographic narratives such as Mary of Egypt, included in Ælfric’s Lives of Saints. The ultimate aim will be to trace how certain “new epistemologies” of flesh in the Anglo-Saxon period might have important implications in relation to writing a longue durée biohistory. I will also explore what happens in the contemporary present when power is no longer wholly centralized in a sovereign body of any sort, but rather has become dispersed into transnational (and often illegal) zones and networks and dynamic webs of “hybrid contaminations,” where the “absolute life of the whole body [may be] immaterial.”[2]

ENDNOTES

1. To hear some of Kathleen Biddick's recent commentary on sovereignty, bare life, and biopower in the Middle Ages, see Kathleen Biddick, “Toy Stories: Vita Nuda, Then and Now?” [audiofile from "Speculative Medievalisms 1: A Laboratory-Atelier," King's College London, 14 January 2011.

2. See Mrinalini Chakravorty and Leila Neti, “The Human Recycled: Insecurity in the Transitional Moment,” differences 20.2/3 (2009): 194-223.